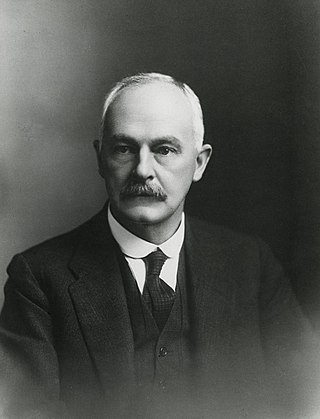

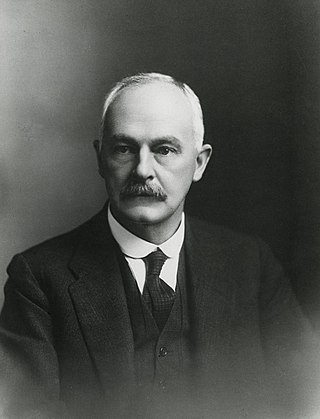

Frederick Soddy FRS was an English radiochemist who explained, with Ernest Rutherford, that radioactivity is due to the transmutation of elements, now known to involve nuclear reactions. He also proved the existence of isotopes of certain radioactive elements. In 1921 he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for his contributions to our knowledge of the chemistry of radioactive substances, and his investigations into the origin and nature of isotopes". Soddy was a polymath who mastered chemistry, nuclear physics, statistical mechanics, finance and economics.

Otto Hahn was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner discovered radioactive isotopes of radium, thorium, protactinium and uranium. He also discovered the phenomena of atomic recoil and nuclear isomerism, and pioneered rubidium–strontium dating. In 1938, Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann discovered nuclear fission, for which Hahn received the 1944 Nobel Prize for Chemistry. Nuclear fission was the basis for nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons.

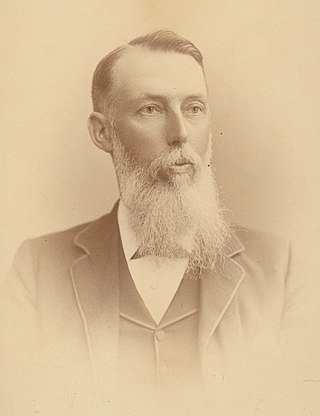

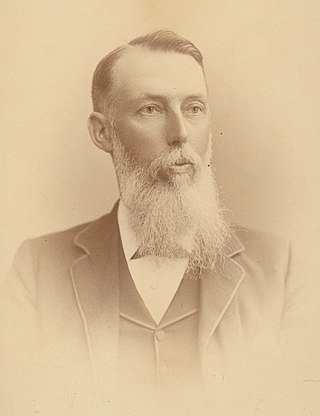

Sir William Ramsay was a Scottish chemist who discovered the noble gases and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous elements in air" along with his collaborator, John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics that same year for their discovery of argon. After the two men identified argon, Ramsay investigated other atmospheric gases. His work in isolating argon, helium, neon, krypton, and xenon led to the development of a new section of the periodic table.

Friedrich Ernst Dorn was a German physicist who was the first to discover that a radioactive substance, later named radon, is emitted from radium.

Robert H. Whytlaw-Gray, OBE, FRS was an English chemist, born in London. He studied at the University of Glasgow and University College London and was Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at the University of Leeds. He and William Ramsay isolated radon and studied its physical properties.

Colin Grant Clark was a British and Australian economist and statistician who worked in both the United Kingdom and Australia. He pioneered the use of gross national product (GNP) as the basis for studying national economies.

Thomas Parnell was the first Professor of Physics at the University of Queensland. He started the famous pitch drop experiment there.

Sir David Orme Masson KBE FRS FRSE LLD was a scientist born in England who emigrated to Australia to become Professor of Chemistry at the University of Melbourne. He is known for his work on the explosive compound nitroglycerin.

Sir Harry Brookes Allen was an Australian pathologist.

Bertram Borden Boltwood was an American pioneer of radiochemistry.

Henry Caselli Richards, was an Australian professor of geology, academic and teacher.

Edward Henry Rennie was an Australian scientist and a president of the Royal Society of South Australia.

Thomas Howell Laby FRS, was an Australian physicist and chemist, Professor of Natural Philosophy, University of Melbourne 1915–1942. Along with George Kaye, he was one of the founding editors of the reference book Tables of Physical and Chemical Constants and Some Mathematical Functions, usually known simply as "Kaye and Laby".

Oscar Werner Tiegs FRS FAA was an Australian zoologist whose career spanned the first half of the 20th century.

Sir Leslie Harold Martin, was an Australian physicist. He was one of the 24 Founding Fellows of the Australian Academy of Science and had a significant influence on the structure of higher education in Australia as chairman of the Australian Universities Commission from 1959 until 1966. He was Professor of Physics at the University of Melbourne from 1945 to 1959, and Dean of the Faculty of Military Studies and Professor of Physics at the University of New South Wales at the Royal Military College, Duntroon, in Canberra from 1967 to 1970. He was the Defence Scientific Adviser and chairman of the Defence Research and Development Policy Committee from 1948 to 1968, and a member of the Australian Atomic Energy Commission from 1958 to 1968. In this role he was an official observer at several British nuclear weapons tests in Australia.

Great Court is a heritage-listed university colonnade at the University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. It was designed by John (Jack) Hennessy and built from 1937 to 1979. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 8 March 2002.

Howard Turner Barnes was an American-Canadian physicist who specialized in calorimetry, electrolytes, ice formation and ice engineering.

Sir John Percival Vissing Madsen FAA was an Australian academic, physicist, engineer, mathematician and Army officer.

Frank William Ernest Gibson was an Australian biochemist and molecular biologist, Howard Florey Professor of Medical Research in the John Curtin School of Medical Research, and a Fellow of the Royal Society of London He undertook his most notable work at the University of Melbourne. He and his research group were responsible for the discovery of chorismic acid. He later worked at The Australian National University (ANU).

Herbert Edmeston Watson was Ramsay Memorial Professor of Chemical Engineering at University College London and the inventor of the low voltage neon glow lamp.