Related Research Articles

The Tibetic languages form a well-defined group of languages descending from Old Tibetan. According to Nicolas Tournadre, there are 50 Tibetic languages, which branch into more than 200 dialects, which could be grouped into eight dialect continua. These Tibetic languages are spoken in Tibet, the greater Tibetan Plateau, and in the Himalayas in Gilgit-Baltistan, Ladakh, Aksai Chin, Nepal, and in India at Himachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand. Classical Tibetan is the major literary language, particularly for its use in Tibetan Buddhist scriptures and literature.

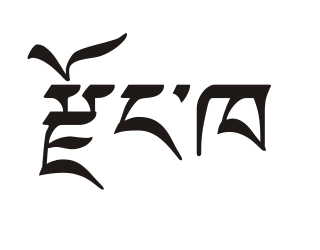

Dzongkha is a Tibeto-Burman language that is the official and national language of Bhutan. It is written using the Tibetan script.

Trashigang District is Bhutan's easternmost dzongkhag (district).

Trashiyangtse District is one of the twenty dzongkhags (districts) comprising Bhutan. It was created in 1992 when Trashiyangtse district was split off from Trashigang District. Trashiyangtse covers an area of 1,437.9 square kilometres (555.2 sq mi). At an elevation of 1750–1880 m, Trashi yangtse dzongkhag is rich of culture filled with sacred places blessed by Guru Rimpoche and dwelled by Yangtseps, Tshanglas, Bramis from Tawang, Khengpas from Zhemgang and Kurtoeps from Lhuentse.

The Sharchops are the populations of mixed Tibetan, Southeast Asian and South Asian descent that mostly live in the eastern districts of Bhutan.

The Ngalop are people of Tibetan origin who migrated to Bhutan as early as the ninth century. Orientalists adopted the term "Bhote" or Bhotiya, meaning "people of Bod (Tibet)", a term also applied to the Tibetan people, leading to confusion, and now is rarely used in reference to the Ngalop.

Articles related to Bhutan include:

The Kheng people are found primarily in the Zhemgang, Trongsa, Bumthang, Dagana, and Mongar Districts of central Bhutan. They speak the Kheng language, a member of the extended Sino-Tibetan language family belonging to the East Bodish languages group; it is mutually intelligible with the Bumthang language and Kurtöp language to the north. The Kheng people are ethnolinguistically same as the Bumthang people and Kurtöp people of central Bhutan and are more closely related to Ngalop people of western Bhutan than to their neighbors in eastern Bhutan, who are primarily Sharchops and speak Tshangla language. SIL International estimates there are 50,000 Kheng speakers as of 2009.

Tshangla is a Sino-Tibetan language of the Bodish branch closely related to the Tibetic languages. Tshangla is primarily spoken in Eastern Bhutan and acts as a lingua franca in the region; it is also spoken in the adjoining Tawang tract in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh and the Pemako region of Tibet. Tshangla is the principal pre-Tibetan language of Bhutan.

Christians are estimated to make up approximately 1% of the population in Bhutan, or approximately 8,000 people. Other figures suggest that they are more than 2% of the population.

There are two dozen languages of Bhutan, all members of the Tibeto-Burman language family except for Nepali, which is an Indo-Aryan language, and the Bhutanese Sign Language. Dzongkha, the national language, is the only native language of Bhutan with a literary tradition, though Lepcha and Nepali are literary languages in other countries. Other non-Bhutanese minority languages are also spoken along Bhutan's borders and among the primarily Nepali-speaking Lhotshampa community in South and East Bhutan. Chöke is the language of the traditional literature and learning of the Buddhist monastics.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Bhutan:

Bodish, named for the Tibetan ethnonym Bod, is a proposed grouping consisting of the Tibetic languages and associated Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in Tibet, North India, Nepal, Bhutan, and North Pakistan. It has not been demonstrated that all these languages form a clade, characterized by shared innovations, within Sino-Tibetan.

The East Bodish languages are a small group of non-Tibetic Bodish languages spoken in eastern Bhutan and adjacent areas of Tibet and India. They include:

Gongduk or Gongdu is an endangered Sino-Tibetan language spoken by about 1,000 people in a few inaccessible villages located near the Kuri Chhu river in the Gongdue Gewog of Mongar District in eastern Bhutan. The names of the villages are Bala, Dagsa, Damkhar, Pam, Pangthang, and Yangbari (Ethnologue).

ʼOle, also called ʼOlekha or Black Mountain Monpa, is a possibly Sino-Tibetan language spoken by about 1,000 people in the Black Mountains of Wangdue Phodrang and Trongsa Districts in western Bhutan. The term ʼOle refers to a clan of speakers.

The Pemakö dialect is a dialect of the Tshangla language. It is the predominant speech in the Pemako region of the Tibet Autonomous Region and an adjoining contiguous area south of the McMahon line in Arunachal Pradesh in India. Though Tshangla is not a Tibetic language, it shares many similarities with Classical Tibetan, particularly in its vocabulary. Many Tibetan loanwords are used in Pemako, due to centuries of close contact with various Tibetan tribes in the Pemako area. Pemako Tshangla has undergone tremendous changes due to its isolation and Tibetan influence.

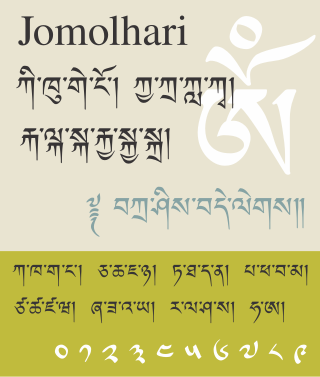

Jomolhari is a Tibetan script Uchen font created by Christopher J. Fynn, freely available under the Open Font License. It supports text encoded using the Unicode Standard and the Chinese national standard for encoding characters of the Tibetan script. The design of the font is based on Bhutanese manuscript examples and it is suitable for text in Tibetan, Dzongkha and other languages written in the Tibetan script. In Latin, it is metrically compatible with Times New Roman.

Bhutanese Literature is written in various languages including Nepali language and Dzongkha in Bhutan. It dates back to the 1950s. Earlier, Bhutanese literature used to be centered on religious teachings, and, now, it is more focused on folklores.