Manuel Lisa, also known as Manuel de Lisa, was a Spanish citizen and later, became an American citizen who, while living on the western frontier, became a land owner, merchant, fur trader, United States Indian agent, and explorer. Lisa was among the founders, in St. Louis, of the Missouri Fur Company, an early fur trading company. Manuel Lisa gained respect through his trading among Native American tribes of the upper Missouri River region, such as the Teton Sioux, Omaha and Ponca.

The Ponca people are a nation primarily located in the Great Plains of North America that share a common Ponca culture, history, and language, identified with two Indigenous nations: the Ponca Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma or the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska.

Susan La Flesche Picotte was a Native American medical doctor and reformer and member of the Omaha tribe. She is widely acknowledged as one of the first Indigenous people, and the first Indigenous woman, to earn a medical degree. She campaigned for public health and for the formal, legal allotment of land to members of the Omaha tribe.

Standing Bear was a Ponca chief and Native American civil rights leader who successfully argued in U.S. District Court in 1879 in Omaha that Native Americans are "persons within the meaning of the law" and have the right of habeas corpus, thus becoming the first Native American judicially granted civil rights under American law. His first wife Zazette Primeau (Primo), daughter of Lone Chief, mother of Prairie Flower and Bear Shield, was also a signatory on the 1879 writ that initiated the famous court case.

The Omaha Tribe of Nebraska are a federally recognized Midwestern Native American tribe who reside on the Omaha Reservation in northeastern Nebraska and western Iowa, United States. There were 5,427 enrolled members as of 2012. The Omaha Reservation lies primarily in the southern part of Thurston County and northeastern Cuming County, Nebraska, but small parts extend into the northeast corner of Burt County and across the Missouri River into Monona County, Iowa. Its total land area is 307.03 sq mi (795.2 km2) and the reservation population, including non-Native residents, was 4,526 in the 2020 census. Its largest community is Pender.

Francis La Flesche was the first professional Native American ethnologist; he worked with the Smithsonian Institution. He specialized in Omaha and Osage cultures. Working closely as a translator and researcher with the anthropologist Alice C. Fletcher, La Flesche wrote several articles and a book on the Omaha, plus more numerous works on the Osage. He made valuable original recordings of their traditional songs and chants. Beginning in 1908, he collaborated with American composer Charles Wakefield Cadman to develop an opera, Da O Ma (1912), based on his stories of Omaha life, but it was never produced. A collection of La Flesche's stories was published posthumously in 1998.

The Elkhorn River is a river in northeastern Nebraska, United States, that originates in the eastern Sandhills and is one of the largest tributaries of the Platte River, flowing 290 miles (470 km) and joining the Platte just southwest of Omaha, approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) south and 3 miles (4.8 km) west of Gretna.

Susette La Flesche, later Susette LaFlesche Tibbles and also called Inshata Theumba, meaning "Bright Eyes", was a well-known Native American writer, lecturer, interpreter, and artist of the Omaha tribe in Nebraska. La Flesche was a progressive who was a spokesperson for Native American rights. She was of Ponca, Iowa, French, and Anglo-American ancestry. In 1983, she was inducted into the Nebraska Hall of Fame. In 1994, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

Thomas Henry Tibbles was an American abolitionist, writer, journalist, Native American rights activist, and politician who was born in Ohio and lived in various other places in the United States, especially Nebraska. Tibbles played an important role in the trial of Standing Bear, a legal battle which led to the liberation of the Ponca tribe from the Indian territory in Oklahoma in the year 1879. This landmark case led to important improvements in the civil rights of Native Americans throughout the country and opened the door to further advancement.

Joseph LaFlesche, also known as E-sta-mah-za or Iron Eye, was the last recognized head chief of the Omaha tribe of Native Americans who was selected according to the traditional tribal rituals. The head chief Big Elk had adopted LaFlesche as an adult into the Omaha and designated him in 1843 as his successor. LaFlesche was of Ponca and French Canadian ancestry; he became a chief in 1853, after Big Elk's death. An 1889 account said that he had been the only chief among the Omaha to have known European ancestry.

Fontenelle's Post, first known as Pilcher's Post, and the site of the later city of Bellevue, was built in 1822 in the Nebraska Territory by Joshua Pilcher, then president of the Missouri Fur Company. Located on the west side of the Missouri River, it developed as one of the first European-American settlements in Nebraska. The Post served as a center for trading with local Omaha, Otoe, Missouri, and Pawnee tribes.

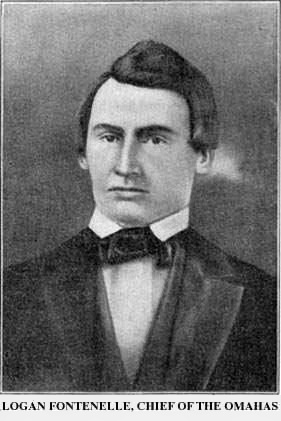

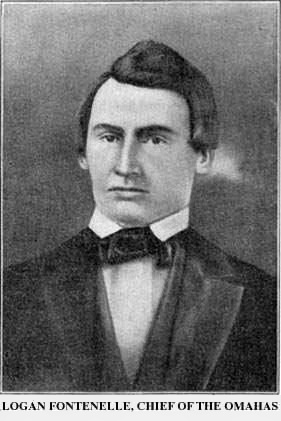

Logan Fontenelle, also known as Shon-ga-ska, was a trader of Omaha and French ancestry, who served for years as an interpreter to the US Indian agent at the Bellevue Agency in Nebraska. He was especially important during the United States negotiations with Omaha leaders in 1853–1854 about ceding land to the United States prior to settlement on a reservation. His mother was a daughter of Big Elk, the principal chief, and his father was a respected French-American fur trader.

Fontenelle Forest is a 1,500-acre (6 km2) forest, located in Bellevue, Nebraska. Its visitor features include hiking trails, a nature center, children's camps, a gift shop, and picnic facilities. The forest is listed as a National Natural Landmark and a National Historic District. The forest includes hardwood deciduous forest, extensive floodplain, loess hills, and marshlands.

Peter Abadie Sarpy was a French-American entrepreneur and fur trader. He was the owner and operator of several fur trading posts essential to the development of the Nebraska Territory and a thriving ferry business. Also, he helped plan the towns of Bellevue and Decatur, Nebraska. Nebraska's legislature named Sarpy County after him in honor of his service to the state.

The Nemaha Half-Breed Reservation was established by the Fourth Treaty of Prairie du Chien of 1830, which set aside a tract of land for the mixed-ancestry descendants of French-Canadian trappers and women of the Oto, Iowa, and Omaha, as well as the Yankton and Santee Sioux tribes.

French people have been present in the U.S. state of Nebraska since before it achieved statehood in 1867. The area was originally claimed by France in 1682 as part of La Louisiane, the extent of which was largely defined by the watershed of the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Over the following centuries, explorers of French ethnicity, many of them French-Canadian, trapped, hunted, and established settlements and trading posts across much of the northern Great Plains, including the territory that would eventually become Nebraska, even in the period after France formally ceded its North American claims to Spain. During the 19th century, fur trading gave way to settlements and farming across the state, and French colonists and French-American migrants continued to operate businesses and build towns in Nebraska. Many of their descendants continue to live in the state.

Lucien Fontenelle was a prominent fur trader in what is now Nebraska in the early-19th century who was born to François and Marie-Louise Fontenelle on the family plantation south of New Orleans. His parents were killed by a hurricane while he was away attending school in New Orleans. He left New Orleans in 1816 after having been raised for a time by an aunt, and began working in the lower-Missouri fur trade in 1819.