Taylor County is a county in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 census, the population was 19,913. Its county seat is Medford. It is mostly rural, lying roughly where corn and dairy farms to the south give way to forest and swamp to the north.

See Cleveland (disambiguation)

Ford is a town in Taylor County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 276 at the 2000 census. The unincorporated community of Polley is located in the town.

Goodrich is a town in Taylor County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 510 at the 2010 census.

Grover is a town in Taylor County, Wisconsin, in the United States. As of the 2010 census, the town population was 256. The unincorporated community of Perkinstown is located in the town.

Hammel is a town in Taylor County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 735 at the 2000 census. The unincorporated community of Murat is located in the town.

Little Black is a town located in Taylor County, Wisconsin. The village of Stetsonville lies partly in the town, and the hamlet of Little Black. As of the 2000 census, the town had a total population of 1,148.

Westboro is a town in Taylor County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 660 at the 2000 census. The census-designated place of Westboro is located in the town. The unincorporated community of Queenstown is also located in the town.

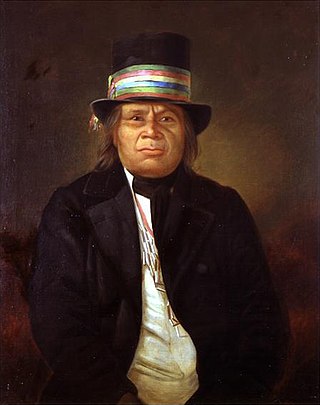

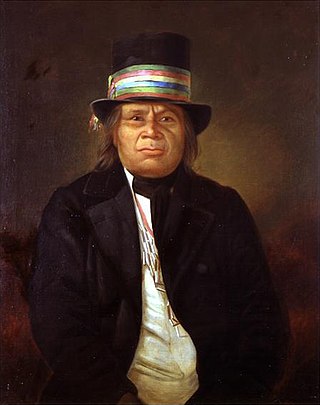

The Ojibwe are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland covers much of the Great Lakes region and the northern plains, extending into the subarctic and throughout the northeastern woodlands. Ojibweg, being Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands and of the subarctic, are known by several names, including Ojibway or Chippewa. As a large ethnic group, several distinct nations also understand themselves to be Ojibwe as well, including the Saulteaux, Nipissings, and Oji-Cree.

Hayward is a city in Sawyer County, Wisconsin, United States, next to the Namekagon River. Its population was 2,533 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Sawyer County. The city is surrounded by the Town of Hayward. The City of Hayward was formally organized in 1883.

Rib Lake is a town in Taylor County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 768 at the 2000 census. The village of Rib Lake is completely surrounded by the town.

The Potawatomi, also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie, are a Native American people of the Great Plains, upper Mississippi River, and western Great Lakes region. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a member of the Algonquian family. The Potawatomi call themselves Neshnabé, a cognate of the word Anishinaabe. The Potawatomi are part of a long-term alliance, called the Council of Three Fires, with the Ojibway and Odawa (Ottawa). In the Council of Three Fires, the Potawatomi are considered the "youngest brother". Their people are referred to in this context as Bodéwadmi, a name that means "keepers of the fire" and refers to the council fire of three peoples.

The Menominee are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans officially known as the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. Their land base is the Menominee Indian Reservation in Wisconsin. Their historic territory originally included an estimated 10 million acres (40,000 km2) in present-day Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The tribe currently has about 8,700 members.

The Lac Courte Oreilles Tribe is one of six federally recognized bands of Ojibwe people located in present-day Wisconsin. It had 7,275 enrolled members as of 2010. The band is based at the Lac Courte Oreilles Indian Reservation in northwestern Wisconsin, which surrounds Lac Courte Oreilles. The main reservation's land is in west-central Sawyer County, but two small plots of off-reservation trust land are located in Rusk, Burnett, and Washburn counties. The reservation was established in 1854 by the second Treaty of La Pointe.

Powers Bluff is a wooded hill in central Wisconsin near Arpin. American Indians lived there until the 1930s, calling it Tah-qua-kik, or Skunk Hill. Because of their religious and ceremonial activities, Tah-qua-kik is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Perkinstown is an unincorporated community located in the town of Grover, Taylor County, Wisconsin, United States. The hamlet is scattered around Lake Kathryn, surrounded by Chequamegon National Forest, 10 miles (16 km) east-northeast of Gilman, reached by County Highway M and several gravel roads.

Chelsea is an unincorporated census-designated place located in the town of Chelsea, Taylor County, Wisconsin, United States. Chelsea is 5 miles (8.0 km) west-southwest of Rib Lake. As of the 2010 census, its population was 113.

Whittlesey is a census-designated place in the town of Chelsea, Taylor County, Wisconsin, United States. Its population was 105 as of the 2010 census.

The Mondeaux Dam Recreation Area is a public park in the forest in the town of Westboro, Wisconsin, United States. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and Work Projects Administration (WPA) created the lake and facilities during the Great Depression.

The Government Boarding School at Lac du Flambeau in Lac du Flambeau, Wisconsin was a school where Native American children of the Ojibwe, Potowatomi and Odawa peoples were taught mainstream American culture from 1895 to 1932. It served grades 1-8, teaching both academic and practical subjects, intended to give children skills needed for their rural societies. The school was converted in 1932 to a day school, serving only Ojibwe children and those nearby of other tribes.