Ultra was the designation adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. Ultra eventually became the standard designation among the western Allies for all such intelligence. The name arose because the intelligence obtained was considered more important than that designated by the highest British security classification then used and so was regarded as being Ultra Secret. Several other cryptonyms had been used for such intelligence.

The Double-Cross System or XX System was a World War II counter-espionage and deception operation of the British Security Service. Nazi agents in Britain – real and false – were captured, turned themselves in or simply announced themselves, and were then used by the British to broadcast mainly disinformation to their Nazi controllers. Its operations were overseen by the Twenty Committee under the chairmanship of John Cecil Masterman; the name of the committee comes from the number 20 in Roman numerals: "XX".

Operation Fortitude was a military deception operation by the Allied nations as part of Operation Bodyguard, an overall deception strategy during the buildup to the 1944 Normandy landings. Fortitude was divided into two subplans, North and South, and had the aim of misleading the German High Command as to the location of the invasion.

Operation Bodyguard was the code name for a World War II deception strategy employed by the Allied states before the 1944 invasion of northwest Europe. Bodyguard set out an overall stratagem for misleading the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht as to the time and place of the invasion. Planning for Bodyguard was started in 1943 by the London Controlling Section, a department of the war cabinet. They produced a draft strategy, referred to as Plan Jael, which was presented to leaders at the Tehran Conference in late November and, despite skepticism due to the failure of earlier deception strategy, approved on 6 December 1943.

Major General Sir Stewart Graham Menzies, was Chief of MI6, the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), from 1939 to 1952, during and after the Second World War.

Operation Mincemeat was a successful British deception operation of the Second World War to disguise the 1943 Allied invasion of Sicily. Two members of British intelligence obtained the body of Glyndwr Michael, a tramp who died from eating rat poison, dressed him as an officer of the Royal Marines and placed personal items on him identifying him as the fictitious Captain William Martin. Correspondence between two British generals that suggested that the Allies planned to invade Greece and Sardinia, with Sicily as merely the target of a feint, was also placed on the body.

Operation Copperhead was a small military deception operation run by the British during the Second World War. It formed part of Operation Bodyguard, the cover plan for the invasion of Normandy in 1944 and was intended to mislead German intelligence as to the location of General Bernard Montgomery. The operation was conceived by Dudley Clarke in early 1944 after he watched the film Five Graves to Cairo. Following the war M. E. Clifton James wrote a book about the operation, I Was Monty's Double. It was later adapted into a film, with James in the lead role.

The London Controlling Section (LCS) was a British secret department established in September 1941, under Oliver Stanley, with a mandate to coordinate Allied strategic military deception during World War II. The LCS was formed within the Joint Planning Staff at the offices of the War Cabinet, which was presided over by Winston Churchill as Prime Minister.

The Abwehr was the German military-intelligence service for the Reichswehr and the Wehrmacht from 1920 to 1945. Although the 1919 Treaty of Versailles prohibited the Weimar Republic from establishing an intelligence organization of their own, they formed an espionage group in 1920 within the Ministry of Defence, calling it the Abwehr. The initial purpose of the Abwehr was defence against foreign espionage: an organizational role which later evolved considerably. Under General Kurt von Schleicher the individual military services' intelligence units were combined and, in 1929, centralized under Schleicher's Ministeramt within the Ministry of Defence, forming the foundation for the more commonly understood manifestation of the Abwehr.

Brigadier Dudley Wrangel Clarke, was an officer in the British Army, known as a pioneer of military deception operations during the Second World War. His ideas for combining fictional orders of battle, visual deception and double agents helped define Allied deception strategy during the war, for which he has been referred to as "the greatest British deceiver of WW2". Clarke was also instrumental in the founding of three famous military units, namely the British Commandos, the Special Air Service and the US Rangers.

Operation Long Jump was an alleged German plan to simultaneously assassinate Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill, and Franklin D. Roosevelt, the "Big Three" Allied leaders, at the 1943 Tehran Conference during World War II. The operation in Iran was to be led by SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny of the Waffen SS. A group of agents from the Soviet Union, led by Soviet spy Gevork Vartanian, uncovered the plot before its inception and the mission was never launched. The assassination plan and its disruption have been popularized by the Russian media with appearances in films and novels.

Wulf Dietrich Christian Schmidt, later known as Harry Williamson was a Danish citizen who became a double agent working for Britain against Nazi Germany during the Second World War under the codename Tate. He was part of the Double Cross System, under which all German agents in Britain were controlled by MI5 and used to deceive Germany. Nigel West singled him out as "one of the seven spies who changed the world."

Ops (B) was an Allied military deception planning department, based in the United Kingdom, during the Second World War. It was set up under Colonel Jervis-Read in April 1943 as a department of Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), an operational planning department with a focus on western Europe. That year, Allied high command had decided that the main Allied thrust would be in southern Europe, and Ops (B) was tasked with tying down German forces on the west coast in general, and drawing out the Luftwaffe in particular.

Colonel John Henry "Johnny" Bevan was a British Army officer who, during the Second World War, made an important contribution to military deception, culminating in Operation Bodyguard, the plan to conceal the D-Day landings in Normandy. In civilian life he was a respected stockbroker in his father's firm.

The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War, by Thaddeus Holt, is a 2004 historical account of Allied military deception during the Second World War. The book focuses primarily on the work of Dudley Clarke in the Middle East, John Bevan in London, Newman Smith in Washington, and Peter Fleming in the Far East, detailing their work in creating strategic and tactical deceptions for the Allied forces.

Colonel Harry Noel Havelock Wild OBE was a British Army officer during the Second World War. He is notable for being second in command of the deception organisation 'A' Force and well as head of Ops. B. He was educated at Eton College.

Operation Graffham was a military deception employed by the Allies during the Second World War. It formed part of Operation Bodyguard, a broad strategic deception designed to disguise the imminent Allied invasion of Normandy. Graffham provided political support to the visual and wireless deception of Operation Fortitude North. The operations together created a fictional threat to Norway during the summer of 1944.

Operation Royal Flush was a military deception employed by the Allied Nations during the Second World War as part of the strategic deception Operation Bodyguard. Royal Flush was a political deception that expanded on the efforts of another Bodyguard deception, Operation Graffham, by emphasising the threat to Norway. It also lent support to parts of Operation Zeppelin via subtle diplomatic overtures to Spain and Turkey. The idea was that information from these neutral countries would filter back to the Abwehr. Planned in April 1944 by Ronald Wingate, Royal Flush was executed throughout June by various Allied ambassadors to the neutral states. During implementation the plan was revised several times to be less extreme in its diplomatic demands. Information from neutral embassies was not well trusted by the Abwehr; as a result, Royal Flush had limited impact on German plans through 1944.

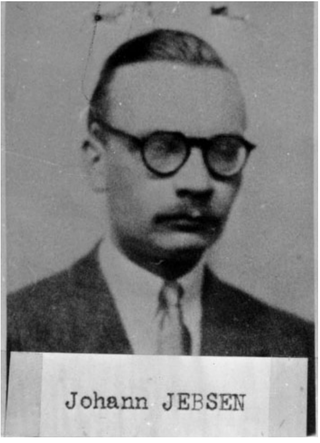

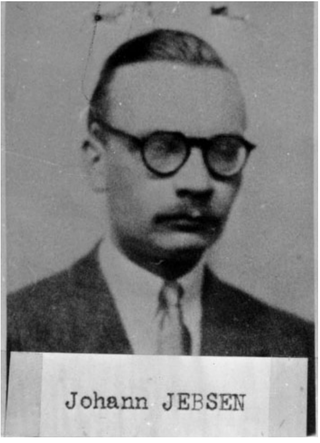

Johann-Nielsen Jebsen, nicknamed "Johnny", was an anti-Nazi German intelligence officer and British double agent during World War II. Jebsen recruited Dušan Popov to the Abwehr and through him later joined the Allied cause. Kidnapped from Lisbon by the Germans shortly before the Normandy landings, Jebsen was tortured in prison and spent time in a concentration camp before disappearing; he was presumed killed at the end of the war.

Operation Ferdinand was a military deception employed by the Allies during the Second World War. It formed part of Operation Bodyguard, a major strategic deception intended to misdirect and confuse German high command about Allied invasion plans during 1944. Ferdinand consisted of strategic and tactical deceptions intended to draw attention away from the Operation Dragoon landing areas in southern France by threatening an invasion of Genoa in Italy. Planned by Eugene Sweeney in June and July 1944 and operated until early September, it has been described as "quite the most successful of 'A' Force's strategic deceptions". It helped the Allies achieve complete tactical surprise in their landings and pinned down German troops in the Genoa region until late July.