Indian English (IE) is a group of English dialects spoken in the Republic of India and among the Indian diaspora. English is used by the Indian government for communication, along with Modern Standard Hindi, as enshrined in the Constitution of India. English is also an official language in seven states and seven union territories of India, and the additional official language in seven other states and one union territory. Furthermore, English is the sole official language of the Indian Judiciary, unless the state governor or legislature mandates the use of a regional language, or if the President of India has given approval for the use of regional languages in courts.

Pather Panchali is a 1955 Indian Bengali-language drama film written and directed by Satyajit Ray in his directoral debut and produced by the Government of West Bengal. It is an adaptation of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay's 1929 Bengali novel of the same name and features Subir Banerjee, Kanu Banerjee, Karuna Banerjee, Uma Dasgupta, Pinaki Sengupta and Chunibala Devi in major roles. The first film in The Apu Trilogy, Pather Panchali depicts the childhood travails of the protagonist Apu and his elder sister Durga amidst the harsh village life of their poor family.

South Asian English is the English accent of many modern-day South Asian countries, inherited from British English dialect. Also known as Anglo-Indian English during the British Raj, the English language was introduced to the Indian subcontinent in the early 17th century and reinforced by the long rule of the British Empire. Today it is spoken as a second language by about 350 million people, 20% of the total population.

Victor Banerjee is an Indian actor who appears in English, Hindi, Bengali and Assamese language films. He has worked with great directors such as Roman Polanski, James Ivory, Sir David Lean, Jerry London, Ronald Neame, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Shyam Benegal, Montazur Rahman Akbar and Ram Gopal Varma. He won the National Film Award for Best Supporting Actor for the film Ghare Baire. He was awarded the Padma Bhushan, India's third highest civilian award, in 2022 by the Indian Government in the field of art.

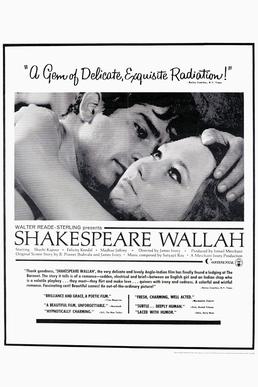

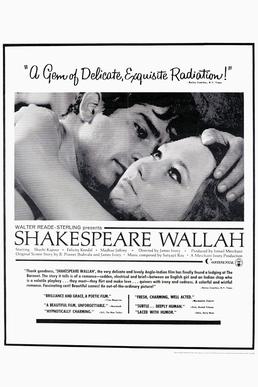

Shakespeare Wallah is a 1965 Merchant Ivory Productions film. The story and screenplay are by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, about a travelling family theatre troupe of English actors in India, who perform Shakespeare plays in towns across India, amidst a dwindling demand for their work and the rise of Bollywood. Madhur Jaffrey won the Silver Bear for Best Actress at the 15th Berlin International Film Festival for her performance. The music was composed by Satyajit Ray.

Utpal Dutt was an Indian actor, director, and writer-playwright. He was primarily an actor in Bengali theatre, where he became a pioneering figure in Modern Indian theatre, when he founded the "Little Theatre Group" in 1949. This group enacted many English, Shakespearean and Brecht plays, in a period now known as the "Epic theatre" period, before it immersed itself completely in highly political and radical theatre. His plays became an apt vehicle for the expression of his Marxist ideologies, visible in socio-political plays such as Kallol (1965), Manusher Adhikar, Louha Manob (1964), Tiner Toloar and Maha-Bidroha. He also acted in over 100 Bengali and Hindi films in a career spanning 40 years, and remains most known for his roles in films such as Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969), Satyajit Ray’s Agantuk (1991), Gautam Ghose’s Padma Nadir Majhi (1992) and Hrishikesh Mukherjee's breezy Hindi comedies such as Gol Maal (1979) and Rang Birangi (1983). He also did the role of a sculptor, Sir Digindra Narayan, in the episode Seemant Heera of Byomkesh Bakshi on Doordarshan in 1993, shortly before his death.

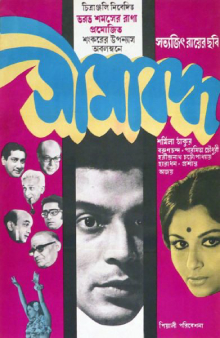

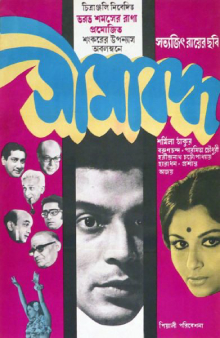

Seemabaddha is a 1971 social drama Bengali film directed by Satyajit Ray. It is based on the novel Seemabaddha by Mani Shankar Mukherjee. It stars Barun Chanda, Harindranath Chattopadhyay, and Sharmila Tagore in lead roles. The film was the second entry in Ray's Calcutta trilogy, which included Pratidwandi (1970) and Jana Aranya (1976). The films deal with the rapid modernization of Calcutta, rising corporate culture and greed, and the futility of the rat race. The film won the FIPRESCI Award at the 33rd Venice International Film Festival, and the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in 1971.

The River is a 1951 American Technicolor drama romance film directed by Jean Renoir shot in Calcutta, India where the Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray, then a student of cinema, met him for guidance. It was fully filmed in India.

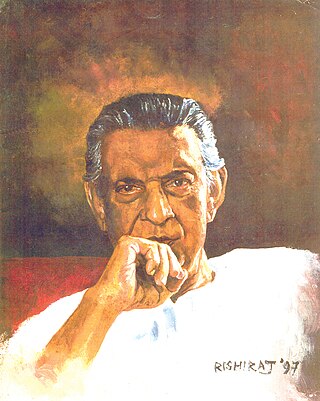

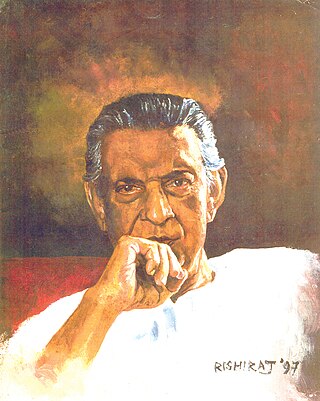

Satyajit Ray was an Indian filmmaker who worked prominently in Bengali cinema and who has often been regarded as one of the greatest directors of world cinema. Ray was born in Calcutta to a Bengali family and started his career as a junior visualiser. His meeting with French film director Jean Renoir, who had come to Calcutta in 1949 to shoot his film The River (1951), and his 1950 visit to London, where he saw Vittorio De Sica's Ladri di biciclette (1948), inspired Ray to become a film-maker. Ray made his directorial debut in 1955 with Pather Panchali and directed 36 films, comprising 29 feature films, five documentaries, and two short films.

Satyajit Ray (1921–1992), a Bengali film director from India, is well known for his contributions to Bengali literature. He created two of the most famous characters in Feluda the sleuth and Professor Shanku the scientist. He wrote several short novels and stories in addition to those based on these two characters. His fiction was targeted mainly at younger readers, though it became popular among children and adults alike.

Indian English has developed a number of dialects, distinct from the General/Standard Indian English that educators have attempted to establish and institutionalise, and it is possible to distinguish a person's sociolinguistic background from the dialect that they employ. These dialects are influenced by the different languages that different sections of the country also speak, side by side with English. The dialects can differ markedly in their phonology, to the point that two speakers using two different dialects can find each other's accents mutually unintelligible.

Chidananda Das Gupta —family name sometimes spelled 'Dashgupta' and 'Dasgupta'—was an Indian filmmaker, film critic, a film historian and one of the founders of Calcutta Film Society with Satyajit Ray in 1947. He lived and worked in Calcutta and Santiniketan.

Calcutta Film Society was India’s second film society in the city of Kolkata, West Bengal, India. It was founded in 1947, just after independence, by Satyajit Ray, Chidananda Dasgupta, RP Gupta, Bansi Chandragupta, Harisadhan Dasgupta and others. The 1925 silent film directed by Sergei Eisenstein, The Battleship Potemkin was the first film screened at the film society, which over the years developed the reputation of having the "most cine-literate audiences in the country". It was revived in 1956 with the efforts of stalwarts like Dasgupta, Vijaya Mulay, Diptendu Pramanick and Satyajit Ray.

Satyajit Ray was an Indian director, screenwriter, documentary filmmaker, author, essayist, lyricist, magazine editor, illustrator, calligrapher, and composer. Ray is widely considered one of the greatest and most influential film directors in the history of cinema. He is celebrated for works including The Apu Trilogy (1955–1959), The Music Room (1958), The Big City (1963) and Charulata (1964) and the Goopy–Bagha trilogy.

Cinema of West Bengal, also known as Tollywood or Bengali cinema, is an Indian film industry of Bengali-language motion pictures. It is based in the Tollygunge region of Kolkata, West Bengal, India. The origins of the nickname Tollywood, a portmanteau of the words Tollygunge and Hollywood, dates back to 1932. It was a historically important film industry, at one time the centre of Indian film production. The Bengali film industry is known for producing many of Indian cinema's most critically acclaimed global Parallel Cinema and art films, with several of its filmmakers gaining prominence at the Indian National Film Awards as well as international acclaim.

The Bengal Club is a social and business club in Kolkata, India. Founded in 1827, the club is the oldest social club in India. When Kolkata was the capital of British India, the club was considered to be the "unofficial headquarters of the Raj". The club is nowadays known for its old-world ambience and patronage among contemporary social and corporate elites, and is among a small number of Indian clubs featured in the elite list of the "Platinum Clubs of the World".

Narayanswamy Viswanathan, popularly known as Calcutta Viswanathan in the Tamil film industry, was an Indian actor and academic. A Tamil by birth, he moved to Calcutta at a young age and taught English at St. Xavier's College, Calcutta for more than 40 years. Viswanathan was also a well-known public speaker. He made his acting debut in Mrinal Sen's Punascha and continued to act in Bengali films. In a career that spanned 40 years, Viswanathan appeared in nearly 100 films in Bengali, Tamil and English. He was a member several theatre groups and also formed the "Calcutta Players", an acting troupe.

Nemai Ghosh was a noted Indian photographer most known for working with Satyajit Ray, as a still photographer for over two decades, starting with Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) till Ray's last film Agantuk (1991).

Anubha Gupta was an Indian Bengali actress and singer who is known for her work in Bengali cinema. She received the Best Actress in Supporting Role Award at the 26th Annual BFJA Awards for the film Hansuli Banker Upakatha.

Pearson Harvey St Regis Surita (1913–1995) was a corporate executive and cricket commentator for All India Radio. Surita hailed from Calcutta and was of Armenian descent. Several articles mention Surita as one of India's most famous and respected radio cricket commentators, often in nostalgic tones. Henry Blofeld twice called Surita India's "greatest cricket commentator ever". Surita's "big moment" as a cricket commentator is said to have come in 1959, when he was invited as a commentator by the BBC, along with the Maharaja of Vizianagram, during India's tour of England the same year. Surita was also an occasional left-arm spin bowler, having played for Calcutta University and a team representing the Maharaja of Cooch Behar in the 1930s, in a one-off match against a visiting Australian team led by Jack Ryder.