Pentlandite is an iron–nickel sulfide with the chemical formula (Fe,Ni)9S8. Pentlandite has a narrow variation range in nickel to iron ratios (Ni:Fe), but it is usually described as 1:1. In some cases, this ratio is skewed by the presence of pyrrhotite inclusions. It also contains minor cobalt, usually at low levels as a fraction of weight.

The platinum-group metals (PGMs), also known as the platinoids, platinides, platidises, platinum group, platinum metals, platinum family or platinum-group elements (PGEs), are six noble, precious metallic elements clustered together in the periodic table. These elements are all transition metals in the d-block.

Cooperite is a grey mineral consisting of platinum sulfide, generally in combinations with sulfides of other elements such as palladium and nickel. Its general formula is (Pt,Pd,Ni)S. It is a dimorph of braggite.

Laurite is an opaque black, metallic ruthenium sulfide mineral with formula: RuS2. It crystallizes in the isometric system. It is in the pyrite structural group. Though it's been found in many localities worldwide, it is extremely rare.

Sperrylite is a platinum arsenide mineral with the chemical formula PtAs2 and is an opaque metallic tin white mineral which crystallizes in the isometric system with the pyrite group structure. It forms cubic, octahedral or pyritohedral crystals in addition to massive and reniform habits. It has a Mohs hardness of 6–7 and a very high specific gravity of 10.6.

Troilite is a rare iron sulfide mineral with the simple formula of FeS. It is the iron-rich endmember of the pyrrhotite group. Pyrrhotite has the formula Fe(1-x)S which is iron deficient. As troilite lacks the iron deficiency which gives pyrrhotite its characteristic magnetism, troilite is non-magnetic.

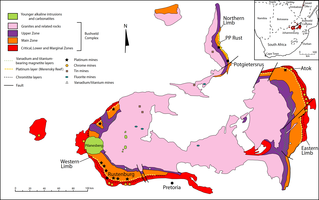

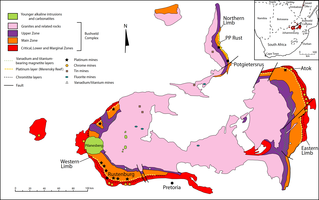

The Bushveld Igneous Complex (BIC) is the largest layered igneous intrusion within the Earth's crust. It has been tilted and eroded forming the outcrops around what appears to be the edge of a great geological basin: the Transvaal Basin. It is approximately 2 billion years old and is divided into four different limbs: the northern, southern, eastern, and western limbs. The Bushveld Complex comprises the Rustenburg Layered suite, the Lebowa Granites and the Rooiberg Felsics, that are overlain by the Karoo sediments. The site was first publicised around 1897 by Gustaaf Molengraaff who found the native South African tribes residing in and around the area.

Various theories of ore genesis explain how the various types of mineral deposits form within Earth's crust. Ore-genesis theories vary depending on the mineral or commodity examined.

A layered intrusion is a large sill-like body of igneous rock which exhibits vertical layering or differences in composition and texture. These intrusions can be many kilometres in area covering from around 100 km2 (39 sq mi) to over 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi) and several hundred metres to over one kilometre (3,300 ft) in thickness. While most layered intrusions are Archean to Proterozoic in age, they may be any age such as the Cenozoic Skaergaard intrusion of east Greenland or the Rum layered intrusion in Scotland. Although most are ultramafic to mafic in composition, the Ilimaussaq intrusive complex of Greenland is an alkalic intrusion.

Cumulate rocks are igneous rocks formed by the accumulation of crystals from a magma either by settling or floating. Cumulate rocks are named according to their texture; cumulate texture is diagnostic of the conditions of formation of this group of igneous rocks. Cumulates can be deposited on top of other older cumulates of different composition and colour, typically giving the cumulate rock a layered or banded appearance.

Gersdorffite or Nickel glance is a nickel arsenic sulfide mineral with formula NiAsS. It crystallizes in the isometric system showing diploidal symmetry. It occurs as euhedral to massive opaque, metallic grey-black to silver white forms. Gersdorffite belongs to a solid solution series with cobaltite, CoAsS. Antimony freely substitutes also leading to ullmannite, NiSbS. It has a Mohs hardness of 5.5 and a specific gravity of 5.9 to 6.33.

A native metal is any metal that is found pure in its metallic form in nature. Metals that can be found as native deposits singly or in alloys include aluminium, antimony, arsenic, bismuth, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, indium, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, niobium, rhenium, selenium, tantalum, tellurium, tin, titanium, tungsten, vanadium, and zinc, as well as the gold group and the platinum group. Among the alloys found in native state have been brass, bronze, pewter, German silver, osmiridium, electrum, white gold, silver-mercury amalgam, and gold-mercury amalgam.

Heazlewoodite, Ni3S2, is a rare sulfur-poor nickel sulfide mineral found in serpentinitized dunite. It occurs as disseminations and masses of opaque, metallic light bronze to brassy yellow grains which crystallize in the trigonal crystal system. It has a hardness of 4, a specific gravity of 5.82. Heazlewoodite was first described in 1896 from Heazlewood, Tasmania, Australia.

The Stillwater igneous complex is a large layered mafic intrusion (LMI) located in southern Montana in Stillwater, Sweet Grass and Park Counties. The complex is exposed across 30 miles (48 km) of the north flank of the Beartooth Mountain Range. The complex has extensive reserves of chromium ore and has a history of being mined for chromium. More recent mining activity has produced palladium and other platinum group elements.

Louis Jean-Pierre Cabri (born February 23, 1934 in Cairo) is an eminent Canadian scientist in the field of platinum group elements (PGE) mineralogy with expertise in precious metal mineralogy and base metals at the Canada Centre for Mineral and Energy Technology (CANMET). First as Research Scientist and later as Principal Scientist (1996–1999). In the 1970s he discovered two new Cu–Fe sulfide minerals, "mooihoekite" and "haycockite". In 1983 Russian mineralogists named a new mineral after him: cabriite (Pd2SnCu).

Mooihoekite is a copper iron sulfide mineral with chemical formula of Cu9Fe9S16. The mineral was discovered in 1972 and received its name from its discovery area, the Mooihoek mine in Transvaal, South Africa.

Millerite is a nickel sulfide mineral, NiS. It is brassy in colour and has an acicular habit, often forming radiating masses and furry aggregates. It can be distinguished from pentlandite by crystal habit, its duller colour, and general lack of association with pyrite or pyrrhotite.

Köttigite is a rare hydrated zinc arsenate which was discovered in 1849 and named by James Dwight Dana in 1850 in honour of Otto Friedrich Köttig (1824–1892), a German chemist from Schneeberg, Saxony, who made the first chemical analysis of the mineral. It has the formula Zn3(AsO4)2·8H2O and it is a dimorph of metaköttigite, which means that the two minerals have the same formula, but a different structure: köttigite is monoclinic and metaköttigite is triclinic. There are several minerals with similar formulae but with other cations in place of the zinc. Iron forms parasymplesite Fe2+3(AsO4)2·8H2O; cobalt forms the distinctively coloured pinkish purple mineral erythrite Co3(AsO4)2·8H2O and nickel forms annabergite Ni3(AsO4)2·8H2O. Köttigite forms series with all three of these minerals and they are all members of the vivianite group.

Ferronickel platinum is a very rarely occurring minerals from the mineral class of elements (including natural alloys, intermetallic compounds, carbides, nitrides, phosphides and silicides) with the chemical composition Pt2FeNi and thus is chemically seen as a natural alloy, more precisely an intermetallic compound of platinum, nickel and iron in a ratio of 2:1:1.

Palladium(II) sulfide is a chemical compound of palladium and sulfur with the chemical formula PdS. Like other palladium and platinum chalcogenides, palladium(II) sulfide has complex structural, electrical and magnetic properties.