The massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia were carried out in German-occupied Poland by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) with the support of parts of the local Ukrainian population against the Polish minority in Volhynia, Eastern Galicia, parts of Polesia and the Lublin region from 1943 to 1945. The ruling Germans also actively encouraged both Ukrainians and Poles to kill each other.

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera was a Ukrainian far-right leader of the radical militant wing of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the OUN-B.as well as a Nazi

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army was a Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary and partisan formation founded by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists on 14 October 1942. During World War II, it was engaged in guerrilla warfare against Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and both the Polish Underground State and Polish Communists. It conducted the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.

The Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists was a Ukrainian nationalist organization established in 1929 in Vienna, uniting the Ukrainian Military Organization with smaller, mainly youth, radical nationalist right-wing groups. The OUN was the largest and one of the most important far-right Ukrainian organizations operating in the interwar period on the territory of the Second Polish Republic. The OUN was mostly active preceding, during, and immediately after the Second World War. Its ideology has been described as having been influenced by the writings of Dmytro Dontsov, from 1929 by Italian fascism, and from 1930 by German Nazism. The OUN pursued a strategy of violence, terrorism, and assassinations with the goal of creating an ethnically homogenous and totalitarian Ukrainian state.

Roman-Taras Yosypovych Shukhevych was a Ukrainian nationalist and a military leader of the nationalist Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which during the Second World War fought against the Soviet Union and to a lesser extent against the Nazi Germany for Ukrainian independence. He collaborated with the Nazis from February 1941 to December 1942 as commanding officer of the Nachtigall Battalion in early 1941, and as a Hauptmann of the German Schutzmannschaft 201 auxiliary police battalion in late 1941 and 1942.

The 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS , commonly referred to as the Galicia Division, was a World War II infantry division of the Waffen-SS, the military wing of the German Nazi Party, made up predominantly of volunteers with a Ukrainian ethnic background from the area of Galicia, later also with some Slovaks.

Pavlivka is a town now located in northwestern Ukraine, in Volodymyr Raion of Volyn Oblast, near Volodymyr, on the Luha river. For centuries, Poryck was property of several noble Polish families. The town is the birthplace of a Polish statesman Tadeusz Czacki. On 11 July 1943, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, supported by local nationalists murdered here more than 300 Polish civilians, who had gathered in a local Roman Catholic church for a Sunday ceremony.

Mykola Kyrylovych Lebed was a Ukrainian nationalist political activist and guerrilla fighter. He was among those tried, convicted, and imprisoned for the murder of Polish interior minister Bronisław Pieracki in 1934. The court sentenced him to death, but the state commuted the sentence to life imprisonment. He escaped when the Germans invaded Poland in 1939. As a leader of OUN-B, he was responsible for the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.

Dmytro Semenovych Klyachkivsky, also known by the pseudonyms of Klym Savur, Okhrim, and Bilash, was a commander of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) and the first head-commander of UPA-North. He was responsible for the ethnic cleansing of Poles from Volhynia.

Kisielin massacre was a massacre of Polish worshipers which took place in the Volhynian village of Kisielin, now Kysylyn, located in the Volyn Oblast, Ukraine. It took place on Sunday, July 11, 1943, when units of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), supported by local Ukrainian peasants, surrounded Poles who had gathered for a ceremony at a local Roman-Catholic church. Around 60 to 90 persons or more, men, women and children – were ordered to take off their clothes and were then massacred by machine gun. The wounded were killed with weapons such as axes and knives. Those who survived escaped to the presbytery and barricaded themselves for eleven hours.

This article presents the historiography of the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, as presented by historians in Poland and Ukraine after World War II.

Ewa Siemaszko is a Polish writer, publicist and lecturer; collector of oral accounts and historical data regarding the Massacres of Poles in Volhynia. An engineer by profession with Master's in technological studies from the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Siemaszko worked in public health education and also as a school teacher following graduation. She is a daughter of writer Władysław Siemaszko with whom she collaborates and shares strong interest in Polish World War II history.

Było sobie miasteczko... is a 2009 Polish historical documentary film about the 1943 Kisielin massacre in the village of Kisielin, located in the Wołyń Voivodeship in Poland before World War II,. The film, directed by Tadeusz Arciuch and Maciej Wojciechowski, was produced by Adam Kruk for Telewizja Polska.

Per Anders Rudling is a Swedish-American historian and an associate professor in the Department of History at Lund University (Sweden). He specializes in the areas of nationalism.

A Banderite or Banderovite was a member of OUN-B, a faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. The term, used from late 1940 onward, derives from the name of Stepan Bandera (1909–1959), the ultranationalist leader of this faction of the OUN. Because of the brutality utilized by OUN-B members, the colloquial term Banderites quickly earned a negative connotation, particularly among Poles and Jews. By 1942, the expression was well-known and frequently used in western Ukraine to describe the Ukrainian Insurgent Army partisans, OUN-B members or any other Ukrainian perpetrators. The OUN-B had been engaged in various atrocities, including murder of civilians, most of whom were ethnic Poles, Jews, and Romani people.

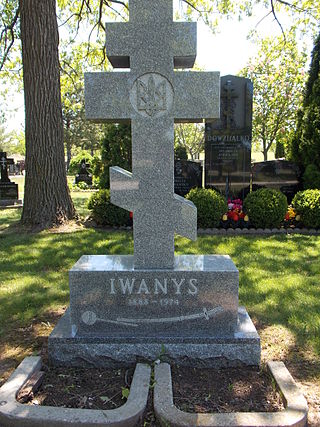

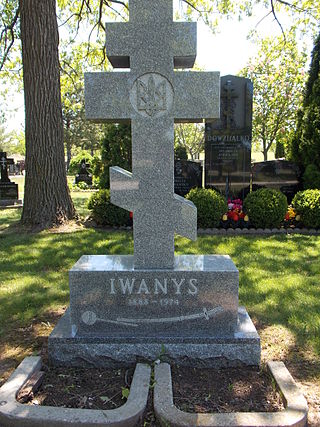

St. Volodymyr Ukrainian Cemetery, marketed as West Oak Memorial Gardens, is a cemetery in Oakville, Ontario, established in 1984. According to the cemetery's website, it is operated by St. Volodymyr Cathedral. The cemetery offers both in ground burial and burial vaults in perpetuity, and is open to all those of Christian faith.

The anti-Soviet resistance by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army was a guerrilla war waged by Ukrainian nationalist partisan formations against the Soviet Union in the western regions of the Ukrainian SSR and southwestern regions of the Byelorussian SSR, during and after World War II. With the Red Army forces successful counteroffensive against the Nazi Germany and their invasion into western Ukraine in July 1944, UPA resisted the Red Army's advancement with full-scale guerrilla war, holding up 200,000 Soviet soldiers, particularly in the countryside, and was supplying intelligence to the Nazi Sicherheitsdienst (SD) security service.

The National Day of Remembrance of the victims of the Genocide of Citizens of the Polish Republic committed by Ukrainian Nationalists is an official commemorative date in Poland, marked on July 11. The date was chosen because it was the peak in 1943 of the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia when armed units of Ukrainian nationalists simultaneously attacked 99 settlements inhabited by ethnic Poles.

Canada has several monuments and memorials that to varying degrees commemorate people and groups accused of collaboration with Nazi forces.

The United States has monuments to people who collaborated with the Nazis, that are located in New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Wisconsin, Ohio, Alabama, Georgia, and Michigan.