Related Research Articles

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to a psychiatric disease at the time of the criminal act. This is contrasted with an excuse of provocation, in which the defendant is responsible, but the responsibility is lessened due to a temporary mental state. It is also contrasted with the justification of self defense or with the mitigation of imperfect self-defense. The insanity defense is also contrasted with a finding that a defendant cannot stand trial in a criminal case because a mental disease prevents them from effectively assisting counsel, from a civil finding in trusts and estates where a will is nullified because it was made when a mental disorder prevented a testator from recognizing the natural objects of their bounty, and from involuntary civil commitment to a mental institution, when anyone is found to be gravely disabled or to be a danger to themself or to others.

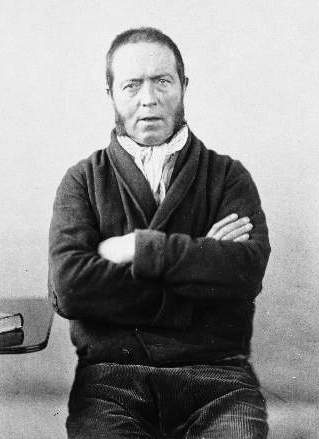

The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal test defining the defence of insanity that was formulated by the House of Lords in 1843. It is the established standard in UK criminal law. Versions have been adopted in some US states, currently or formerly, and other jurisdictions, either as case law or by statute. Its original wording is a proposed jury instruction:

that every man is to be presumed to be sane, and ... that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.

Antisocial personality disorder, often abbreviated to ASPD, is a mental disorder defined by a chronic pattern of behavior that disregards the rights and well-being of others. People with ASPD often exhibit behavior that conflicts with social norms, leading to issues with interpersonal relationships, employment, and legal matters. The condition generally manifests in childhood or early adolescence, with a high rate of associated conduct problems and a tendency for symptoms to peak in late adolescence and early adulthood.

There was systematic political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union, based on the interpretation of political opposition or dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.

Forensic psychiatry is a subspeciality of psychiatry and is related to criminology. It encompasses the interface between law and psychiatry. According to the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, it is defined as "a subspecialty of psychiatry in which scientific and clinical expertise is applied in legal contexts involving civil, criminal, correctional, regulatory, or legislative matters, and in specialized clinical consultations in areas such as risk assessment or employment." A forensic psychiatrist provides services – such as determination of competency to stand trial – to a court of law to facilitate the adjudicative process and provide treatment, such as medications and psychotherapy, to criminals.

Park Elliot Dietz is a forensic psychiatrist who has consulted or testified in many of the highest-profile US criminal cases, including those of spousal killer Betty Broderick, mass murderer Jared Lee Loughner, and serial killers Joel Rifkin, Arthur Shawcross, Jeffrey Dahmer, Ted Kaczynski, Richard Kuklinski, the D.C. sniper attacks, and William Bonin.

In criminal law, automatism is a rarely used criminal defence. It is one of the mental condition defences that relate to the mental state of the defendant. Automatism can be seen variously as lack of voluntariness, lack of culpability (unconsciousness) or excuse. Automatism means that the defendant was not aware of his or her actions when making the particular movements that constituted the illegal act.

Hervey Milton Cleckley was an American psychiatrist and pioneer in the field of psychopathy. His book, The Mask of Sanity, originally published in 1941 and revised in new editions until the 1980s, provided the first clinical description of psychopathy. He defined the term somewhat more broadly than it is understood today, as referring to somebody who behaves in a destructive manner despite lacking overt signs of psychosis or neurosis; this is reflected in the term "mask of sanity", derived from Cleckley's belief that a psychopath can appear normal and even engaging, but that the "mask" conceals a mental disorder. By the time of his death, Cleckley was better remembered for a vivid case study of a female patient, published as a book in 1956 and turned into a movie, The Three Faces of Eve, in 1957. His report of the case (re)popularized the diagnosis of multiple personality disorder in America. The concept of psychopathy continues to be influential through forming parts of the diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder, the Psychopathy Checklist, and public perception.

Psychopathy, or psychopathic personality, is a personality construct characterized by impaired empathy and remorse, in combination with traits of boldness, disinhibition, and egocentrism. These traits are often masked by superficial charm and immunity to stress, which create an outward appearance of apparent normalcy.

In the law of England and Wales, fitness to plead is the capacity of a defendant in criminal proceedings to comprehend the course of those proceedings. The concept of fitness to plead also applies in Scots and Irish law. Its United States equivalent is competence to stand trial.

The Psychopathy Checklist or Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised, now the Psychopathy Checklist—revised (PCL-R), is a psychological assessment tool that is commonly used to assess the presence and extent of psychopathy in individuals—most often those institutionalized in the criminal justice system—and to differentiate those high in this trait from those with antisocial personality disorder, a related diagnosable disorder. It is a 20-item inventory of perceived personality traits and recorded behaviors, intended to be completed on the basis of a semi-structured interview along with a review of "collateral information" such as official records. The psychopath tends to display a constellation or combination of high narcissistic, borderline, and antisocial personality disorder traits, which includes superficial charm, charisma/attractiveness, sexual seductiveness and promiscuity, affective instability, suicidality, lack of empathy, feelings of emptiness, self-harm, and splitting. In addition, sadistic and paranoid traits are usually also present.

Atascadero State Hospital, formally known as California Department of State Hospitals - Atascadero (DSHA), is located on the Central Coast of California, in San Luis Obispo County, halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. DSHA is an all-male, maximum-security facility, forensic institution that houses mentally ill convicts who have been committed to psychiatric facilities by California's courts. Located on a 700+ acre grounds in the city of Atascadero, California, it is the largest employer in that town. DSHA is not a general purpose public hospital, and the only patients admitted are those that are referred to the hospital by the Superior Court, Board of Prison Terms, or the Department of Corrections.

The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry is a 2011 book written by British author Jon Ronson in which he explores the concept of psychopathy, along with the broader mental health "industry" including mental health professionals and the mass media. It spent the whole of 2012 on United Kingdom bestseller lists and ten weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to psychiatry:

Julius Ludwig August Koch was a German psychiatrist whose work influenced later concepts of personality disorders.

Mental health in Russia is covered by a law, known under its official name—the Law of the Russian Federation "On Psychiatric Care and Guarantees of Citizens' Rights during Its Provision", which is the basic legal act that regulates psychiatric care in the Russian Federation and applies not only to persons with mental disorders but all citizens. A notable exception of this rule is those vested with parliamentary or judicial immunity. Providing psychiatric care is regulated by a special law regarding guarantees of citizens' rights.

Psychopathy, from psych and pathy, was coined by German psychiatrists in the 19th century and originally just meant what would today be called mental disorder, the study of which is still known as psychopathology. By the turn of the century 'psychopathic inferiority' referred to the type of mental disorder that might now be termed personality disorder, along with a wide variety of other conditions now otherwise classified. Through the early 20th century this and other terms such as 'constitutional (inborn) psychopaths' or 'psychopathic personalities', were used very broadly to cover anyone who violated legal or moral expectations or was considered inherently socially undesirable in some way.

AH vs West London Mental Health Trust was a landmark case in England, which established a legal precedent in 2011 when Albert Laszlo Haines (AH), a patient in Broadmoor Hospital, a high security psychiatric hospital, was able to exercise a right to a fully open public mental health review tribunal to hear his appeal for release. The case and the legal principles it affirmed have been described as opening up the secret world of tribunals and National Health Service secure units, and as having substantial ramifications for mental health professionals and solicitors, though how frequently patients will be willing or able to exercise the right is not yet clear.

Jürgen Leo Müller is a German medical specialist for neurology and psychiatry. He is a professor for forensic psychiatry and psychotherapy at the University of Göttingen as well as chief physician for forensic psychiatry and psychotherapy at the Asklepios Clinic in Göttingen. His particular scientific interest lies in the empirical research of forensically relevant disorders with a particular focus on personality disorders, psychotherapy as well as violent and sex offenders. In addition to that he places special emphasis on the usability of empirical techniques to responding legal questions.

Herschel Albert Prins (1928–2016) was a British professor of criminology. His career spanned over 60 years in work pertaining to forensic psychiatry, and his appointments included positions at the universities of Leeds, Loughborough, Leicester and Birmingham. His roles included HM probation inspectorate, parole board engagement, and involvement in mental health review tribunals and the mental health act commission. He worked with people with malicious activity, antisocial and disinhibited behaviour, unusual sexual deviations and people who behaved dangerously.

References

- ↑ Seminars in Practical Forensic Psychiatry: Introduction by Derek Chiswick. Published 1995. ISBN 0 902241 78 8. (full text via Royal College of Psychiatrists).

- ↑ Seminars in Practical Forensic Psychiatry: Introduction by Derek Chiswick. Published 1995. ISBN 0 902241 78 8. (full text via Royal College of Psychiatrists).

- ↑ Offenders, Deviants or Patients Herschel Prins, Routledge, 4 Jan 2002

- ↑ Debate in Parliament about the case (Hansard, HC Deb 29 June 1972 vol 839 cc1673-85).

- ↑ Clarkson, Keating & Cunningham. Criminal Law: Texts and Materials. 2007, ISBN 978-0-421-94780-1

- ↑ Jones, Timothy (1995). "Insanity, automatism, and the burden of proof on the accused". Law Quarterly Review (Sweet & Maxwell) 111 (3). ISSN 0023-933X p.475

- ↑ Law Commission: Insanity and Automatism Supplementary Material to the Scoping Paper 18 July 2012. Pg 178-183

- ↑ Federman, C. Holmes, D. Jacob, JD (2009) Deconstructing the psychopath: a critical discursive analysis Cultural Critique, 72

- ↑ Manifest Madness: Mental Incapacity in the Criminal Law Arlie Loughnan, Oxford University Press, 19 Apr 2012

- ↑ Law Commission website: Insanity and Automatism.

- ↑ Law Commission website: Unfitness to Plead