Related Research Articles

The geology of Great Britain is renowned for its diversity. As a result of its eventful geological history, Great Britain shows a rich variety of landscapes across the constituent countries of England, Wales and Scotland. Rocks of almost all geological ages are represented at outcrop, from the Archaean onwards.

Whitmore is a village, civil parish and small curacy in the county of Staffordshire, England, near Newcastle-under-Lyme. Besides Whitmore, the parish also includes the hamlets of Acton, Butterton and Shutlanehead.

The geology of Shropshire is very diverse with a large number of periods being represented at outcrop. The bedrock consists principally of sedimentary rocks of Palaeozoic and Mesozoic age, surrounding restricted areas of Precambrian metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks. The county hosts in its Quaternary deposits and landforms, a significant record of recent glaciation. The exploitation of the Coal Measures and other Carboniferous age strata in the Ironbridge area made it one of the birthplaces of the Industrial Revolution. There is also a large amount of mineral wealth in the county, including lead and baryte. Quarrying is still active, with limestone for cement manufacture and concrete aggregate, sandstone, greywacke and dolerite for road aggregate, and sand and gravel for aggregate and drainage filters. Groundwater is an equally important economic resource.

In geology, an igneous intrusion is a body of intrusive igneous rock that forms by crystallization of magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Intrusions have a wide variety of forms and compositions, illustrated by examples like the Palisades Sill of New York and New Jersey; the Henry Mountains of Utah; the Bushveld Igneous Complex of South Africa; Shiprock in New Mexico; the Ardnamurchan intrusion in Scotland; and the Sierra Nevada Batholith of California.

Volcanic activity is a major part of the geology of Canada and is characterized by many types of volcanic landform, including lava flows, volcanic plateaus, lava domes, cinder cones, stratovolcanoes, shield volcanoes, submarine volcanoes, calderas, diatremes, and maars, along with less common volcanic forms such as tuyas and subglacial mounds.

Guernsey has a geological history stretching further back into the past than most of Europe. The majority of rock exposures on the Island may be found along the coastlines, with inland exposures scarce and usually highly weathered. There is a broad geological division between the north and south of the Island. The Southern Metamorphic Complex is elevated above the geologically younger, lower lying Northern Igneous Complex. Guernsey has experienced a complex geological evolution with multiple phases of intrusion and deformation recognisable.

The geology of Jersey is characterised by the Late Proterozoic Brioverian volcanics, the Cadomian Orogeny, and only small signs of later deposits from the Cambrian and Quaternary periods. The kind of rocks go from conglomerate to shale, volcanic, intrusive and plutonic igneous rocks of many compositions, and metamorphic rocks as well, thus including most major types.

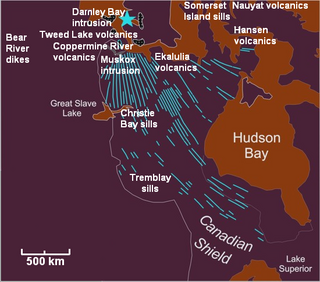

The Mackenzie Large Igneous Province (MLIP) is a major Mesoproterozoic large igneous province of the southwestern, western and northwestern Canadian Shield in Canada. It consists of a group of related igneous rocks that were formed during a massive igneous event starting about 1,270 million years ago. The large igneous province extends from the Arctic in Nunavut to near the Great Lakes in Northwestern Ontario where it meets with the smaller Matachewan dike swarm. Included in the Mackenzie Large Igneous Province are the large Muskox layered intrusion, the Coppermine River flood basalt sequence and the massive northwesterly trending Mackenzie dike swarm.

The Lewisian complex or Lewisian gneiss is a suite of Precambrian metamorphic rocks that outcrop in the northwestern part of Scotland, forming part of the Hebridean Terrane and the North Atlantic Craton. These rocks are of Archaean and Paleoproterozoic age, ranging from 3.0–1.7 billion years (Ga). They form the basement on which the Stoer Group, Wester Ross Supergroup and probably the Loch Ness Supergroup sediments were deposited. The Lewisian consists mainly of granitic gneisses with a minor amount of supracrustal rocks. Rocks of the Lewisian complex were caught up in the Caledonian orogeny, appearing in the hanging walls of many of the thrust faults formed during the late stages of this tectonic event.

The geology of the Isle of Skye in Scotland is highly varied and the island's landscape reflects changes in the underlying nature of the rocks. A wide range of rock types are exposed on the island, sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous, ranging in age from the Archaean through to the Quaternary.

The geology of County Durham in northeast England consists of a basement of Lower Palaeozoic rocks overlain by a varying thickness of Carboniferous and Permo-Triassic sedimentary rocks which dip generally eastwards towards the North Sea. These have been intruded by a pluton, sills and dykes at various times from the Devonian Period to the Palaeogene. The whole is overlain by a suite of unconsolidated deposits of Quaternary age arising from glaciation and from other processes operating during the post-glacial period to the present. The geological interest of the west of the county was recognised by the designation in 2003 of the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty as a European Geopark.

The Cleveland Dyke is an igneous intrusion which extends from Galloway in southern Scotland through Cumbria and County Durham in northern England to the North York Moors in North Yorkshire.

The geology of Tyne and Wear in northeast England largely consists of a suite of sedimentary rocks dating from the Carboniferous and Permian periods into which were intruded igneous dykes during the later Palaeogene Period.

The Acklington Dyke is an igneous intrusion which extends from northwest of Hawick in southern Scotland east-southeastwards through the Borders region towards the North Sea coast of Northumberland in northern England.The dyke is associated with volcanism which took place at the Isle of Mull igneous centre in western Scotland during the early Palaeogene Period at a time of regional crustal tension associated with the opening of the north Atlantic Ocean and which resulted in the intrusion of innumerable dykes. The similar Cleveland Dyke has been dated to 55.8+/- 0.9 Ma. The dyke is composed of tholeiitic microgabbro and basalt Though generally thinner, it is up to 30 m wide in places. It is one of the most significant of a swarm of such intrusions associated with the Mull centre which extend southeastwards through this region, the others being the Cleveland Dyke and the Blyth and Sunderland subswarms of Northumberland and Tyne and Wear. They are grouped as part of the Mull Dyke Swarm which in turn is a part of the North Britain Palaeogene Dyke Suite

The Okavango Dyke Swarm is a giant dyke swarm of the Karoo Large Igneous Province in northeast Botswana, southern Africa. It consists of a group of Proterozoic and Jurassic dykes, trending east-southeast across Botswana, spanning a region nearly 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) long and 110 kilometres (68 mi) wide. The Jurassic dykes were formed approximately 179 million years ago, composed of mainly tholeiitic mafic rocks. The formation is related to the magmatism at the Karoo triple junction, induced by the plate tectonic break up of the Gondwana supercontinent in the early Jurassic.

The geology of the Isle of Man consists primarily of a thick pile of sedimentary rocks dating from the Ordovician period, together with smaller areas of later sedimentary and extrusive igneous strata. The older strata was folded and faulted during the Caledonian and Acadian orogenies The bedrock is overlain by a range of glacial and post-glacial deposits. Igneous intrusions in the form of dykes and plutons are common, some associated with mineralisation which spawned a minor metal mining industry.

The geology of national parks in Britain strongly influences the landscape character of each of the fifteen such areas which have been designated. There are ten national parks in England, three in Wales and two in Scotland. Ten of these were established in England and Wales in the 1950s under the provisions of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. With one exception, all of these first ten, together with the two Scottish parks were centred on upland or coastal areas formed from Palaeozoic rocks. The exception is the North York Moors National Park which is formed from sedimentary rocks of Jurassic age.

The geology of Northumberland National Park in northeast England includes a mix of sedimentary, intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks from the Palaeozoic and Cenozoic eras. Devonian age volcanic rocks and a granite pluton form the Cheviot massif. The geology of the rest of the national park is characterised largely by a thick sequence of sedimentary rocks of Carboniferous age. These are intruded by Permian dykes and sills, of which the Whin Sill makes a significant impact in the south of the park. Further dykes were intruded during the Palaeogene period. The whole is overlain by unconsolidated sediments from the last ice age and the post-glacial period.

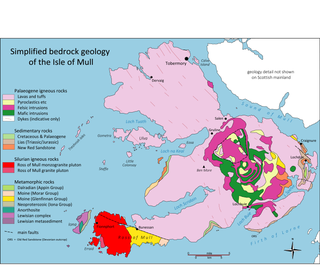

The geology of the Isle of Mull in Scotland is dominated by the development during the early Palaeogene period of a ‘volcanic central complex’ associated with the opening of the Atlantic Ocean. The bedrock of the larger part of the island is formed by basalt lava flows ascribed to the Mull Lava Group erupted onto a succession of Mesozoic sedimentary rocks during the Palaeocene epoch. Precambrian and Palaeozoic rocks occur at the island's margins. A number of distinct deposits and features such as raised beaches were formed during the Quaternary period.

The geology of Pembrokeshire in Wales inevitably includes the geology of the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park which extends around the larger part of the county's coastline and where the majority of rock outcrops are to be seen. Pembrokeshire's bedrock geology is largely formed from a sequence of sedimentary and igneous rocks originating during the late Precambrian and the Palaeozoic era, namely the Ediacaran, Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian and Carboniferous periods, i.e. between 635 and 299 Ma. The older rocks in the north of the county display patterns of faulting and folding associated with the Caledonian Orogeny. On the other hand, the late Palaeozoic rocks to the south owe their fold patterns and deformation to the later Variscan Orogeny.

References

- ↑ "BGS Lexicon of Named Rocks". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ↑ Rees, J.G.; Wilson, A.A. (1998). Geology of the Country around Stoke-on-Trent. British Geological Survey. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0118845373.