Military use

Variations of the military caracole has a long history of usage by various cavalry forces that used missile weapons throughout history. The Scythians and Parthians were thought to use it, while ancient Iberian cavalry famously developed their own variation known as the 'Cantabrian circle'. It was noted in the 13th century to be used by the Mongols of Genghis Khan and also by the Han Chinese military much earlier (likely learning it from their battles with the Xiongnu nomads). It was later revived by European militaries in the mid-16th century in an attempt to integrate gunpowder weapons into cavalry tactics. Equipped with one or more wheellock pistols or similar firearms, cavalrymen would advance on their target at less than a gallop in formation as deep as twelve ranks. As each rank came into range, the soldiers would turn their mount slightly to one side, discharge one pistol, then turn slightly to the other side to discharge another pistol at their target. The horsemen then retired to the back of the formation to reload, and then repeat the manoeuvre. The whole caracole formation might move slowly forward as each rank fired to help press the attack, or move slowly backward to avoid an enemy's advance. Despite this complex manoeuvring, the formation was kept dense rather than open, as the cavalrymen were generally also armed and armoured for melee, and hoped to follow the caracole with a charge. The tactic was accompanied by the increasing popularity of the German Reiter in Western armies from about 1540.

The effectiveness of the caracole is debated. This tactic was often successfully implemented, for instance, at the battle of Pinkie Cleugh, where the mounted Spanish herguletier under Dom Pedro de Gamboa successfully harassed Scottish pike columns. Likewise, at the battle of Dreux mercenary German reiters in the Huguenot employ inflicted huge casualties on the Royal Swiss pike squares, although they failed to break them. At the battle of Lützen in 1632, the Swedish Brigade suffered 50% casualties and retreated from Johann von Götzen's Imperial cuirassier and Ottavio Piccolomini's cavalry arquebusier regiments who used the caracole effectively.

Some historians after Michael Roberts associate the demise of the caracole with the name of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (1594–1632). Certainly he regarded the technique as fairly useless, and ordered cavalry under Swedish command not to use the caracole; instead, he required them to charge aggressively like their Polish-Lithuanian opponents. However, there is plenty of evidence that the caracole was falling out of use by the 1580s at the latest. Henry IV's Huguenot cavalry and Dutch cuirassiers were good examples of cavalry units that abandoned the caracole early on — if they ever used it at all.

According to De la Noue, Henry IV's pistol-armed cavalrymen were instructed to deliver a volley at close quarters and then "charge home" (charge into the enemy). Ranks were reduced from twelve to six, still enough to punch a hole into the classic thin line in which heavy lancers were deployed. That was the tactic usually employed by cavalry since then, and the name reiter was replaced by cuirassier. Sometimes it has been erroneously identified as caracole when low morale cavalry units, instead of charging home, contented themselves with delivering a volley and retire without closing the enemy, but in all those actions the distinctive factor of the caracole, the rolling fire through countermarching, was absent.

The caracole was rarely tried against enemy cavalry, as it could be easily broken when performing the maneuver by a countercharge. The last recorded example of the use of the caracole against enemy cavalry ended in disaster at the battle of Klushino in 1610, when the Polish hussars smashed a unit of Russian reiters, which served as the catalyst for the rout of much of the Russian army. The battle of Mookerheyde (1574) was also another example of the futility in using caracole against aggressive enemy cavalry, as 400 Spanish lancers charged 2,000 German reiters (in Dutch employ) while the second line was reloading their pistols, easily routing the whole force and later the whole Dutch army as well. It is significant that 20 years later, the Dutch cuirassiers easily routed the same Spanish lancers at the battle of Turnhout and the battle of Nieuwpoort, so that according to Charles Oman, in 1603 lancers were finally disbanded from the Spanish army. Nevertheless, variations of caracole tactics continued to be used well into the 17th century against enemy cavalry. During the battle of Gniew of 1626, the Polish light cavalry used it with success twice. The first time light cavalry units under Mikołaj Abramowicz fired at the Swedish cavalry rank by rank, but instead of withdrawing to reload, it immediately proceeded to charge the enemy with sabres. Later the same unit also tried the caracole using gaps in the line of charging husaria heavy cavalry.

16th- and 17th-century sources do not seem to have used the term "caracole" in its modern sense. John Cruso, for example, explained the "caracoll" as a maneuver whereby a formation of cuirassiers received an enemy's charge by wheeling apart to either side, letting the enemy rush in between the pincers of their trap, and then charging inwards against the flanks of the overextended enemy.

Historically, cavalry are groups of soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in the roles of reconnaissance, screening, and skirmishing, or as heavy cavalry for decisive economy of force and shock attacks. An individual soldier in the cavalry is known by a number of designations depending on era and tactics, such as a cavalryman, horseman, trooper, cataphract, knight, drabant, hussar, uhlan, mamluk, cuirassier, lancer, dragoon, samurai or horse archer. The designation of cavalry was not usually given to any military forces that used other animals or platforms for mounts, such as chariots, camels or elephants. Infantry who moved on horseback, but dismounted to fight on foot, were known in the early 17th to the early 18th century as dragoons, a class of mounted infantry which in most armies later evolved into standard cavalry while retaining their historic designation.

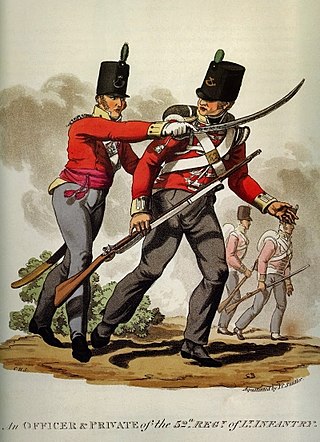

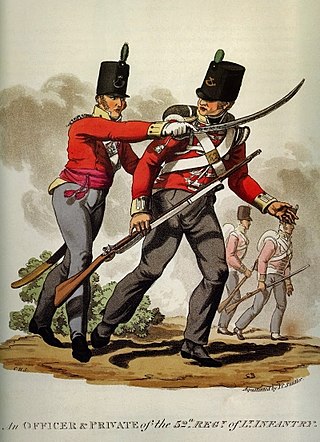

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat with swords and firearms from horseback. While their use goes back to the late 16th century, dragoon regiments were established in most European armies during the 17th and early 18th centuries; they provided greater mobility than regular infantry but were far less expensive than cavalry.

The English term lance is derived, via Middle English launce and Old French lance, from the Latin lancea, a generic term meaning a spear or javelin employed by both infantry and cavalry, with English initially keeping these generic meanings. It developed later into a term for spear-like weapons specially designed and modified to be part of a "weapon system" for use couched under the arm during a charge, being equipped with special features such as grappers to engage with lance rests attached to breastplates, and vamplates, small circular plates designed to prevent the hand sliding up the shaft upon impact. These specific features were in use by the beginning of the late 14th century.

The Polish cavalry can trace its origins back to the days of medieval cavalry knights. Poland is mostly a country of flatlands and fields and mounted forces operate well in this environment. The knights and heavy cavalry gradually evolved into many different types of specialised mounted military formations, some of which heavily influenced western warfare and military science. This article details the evolution of Polish cavalry tactics, traditions and arms from the times of mounted knights and heavy winged hussars, through the times of light uhlans to mounted infantry equipped with ranged and mêlée weapons.

The Grande Armée was the main military component of the French Imperial Army commanded by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1804 to 1808, it won a series of military victories that allowed the French Empire to exercise unprecedented control over most of Europe. Widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest fighting forces ever assembled, it suffered catastophic losses during the disastrous Peninsular War followed by the invasion of Russia in 1812, after which it never recovered its strategic superiority and ended in total defeat for Napoleonic France by the Peace of Paris in 1815.

A charge is an offensive maneuver in battle in which combatants advance towards their enemy at their best speed in an attempt to engage in a decisive close combat. The charge is the dominant shock attack and has been the key tactic and decisive moment of many battles throughout history. Modern charges usually involve small groups of fireteams equipped with weapons with a high rate of fire and striking against individual defensive positions, instead of large groups of combatants charging another group or a fortified line.

Cuirassiers were cavalry equipped with a cuirass, sword, and pistols. Cuirassiers first appeared in mid-to-late 16th century Europe as a result of armoured cavalry, such as men-at-arms and demi-lancers discarding their lances and adopting pistols as their primary weapon. In the later part of the 17th century, the cuirassier lost his limb armour and subsequently wore only the cuirass, and sometimes a helmet. By this time, the sword or sabre had become his primary weapon, with pistols relegated to a secondary function.

The Battle of Breitenfeld or First Battle of Breitenfeld, was fought at a crossroads near Breitenfeld approximately 8 km north-west of the walled city of Leipzig on 17 September, or 7 September, 1631. A Swedish-Saxon army led by King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden and Saxon Elector John George I defeated an Imperial-Catholic League Army led by Generalfeldmarschall Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly. It was the Protestants' first major victory of the Thirty Years War.

Uhlan is a type of light cavalry, primarily armed with a lance. The uhlans started as Lithuanian irregular cavalry, that were later also adopted by other countries during the 18th century, including Poland, France, Russia, Prussia, Saxony, and Austria-Hungary. The term "lancer" was often used interchangeably with "uhlan"; the lancer regiments later formed for the British Army were directly inspired by the uhlans of other armies.

The harquebusier was the most common form of cavalry found throughout Western Europe during the early to mid-17th century. Early harquebusiers were characterised by the use of a type of carbine called a "harquebus". In England, harquebusier was the technical name for this type of cavalry, though in everyday usage they were usually simply called 'cavalry' or 'horse'. In Germany they were often termed Ringerpferd, or sometimes Reiter, in Sweden they were called lätta ryttare.

Reiter or Schwarze Reiter were a type of cavalry in 16th to 17th century Central Europe including Holy Roman Empire, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Tsardom of Russia, and others.

The demi-lancer or demilancer was a type of heavy cavalryman in Western Europe during the 16th and early 17th centuries.

The Coalition forces of the Napoleonic Wars were composed of Napoleon Bonaparte's enemies: the United Kingdom, the Austrian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia, Kingdom of Spain, Kingdom of Naples, Kingdom of Sicily, Kingdom of Sardinia, Dutch Republic, Russian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, Kingdom of Portugal, Kingdom of Sweden, and various German and Italian states at differing times in the wars. At their height, the Coalition could field formidable combined forces of about 1,740,000 strong. This outnumbered the 1.1 million French soldiers. The breakdown of the more active armies are: Austria, 570,000; Britain, 250,000; Prussia, 300,000; and Russia, 600,000.

A close order formation is a military tactical formation in which soldiers are close together and regularly arranged for the tactical concentration of force. It was used by heavy infantry in ancient warfare, as the basis for shield wall and phalanx tactics, to multiply their effective weight of arms by their weight of numbers. In the Late Middle Ages, Swiss pikemen and German Landsknechts used close order formations that were similar to ancient phalanxes.

Heavy cavalry was a class of cavalry intended to deliver a battlefield charge and also to act as a tactical reserve; they are also often termed shock cavalry. Although their equipment differed greatly depending on the region and historical period, heavy cavalry were generally mounted on large powerful warhorses, wore body armor, and armed with either lances, swords, maces, flails (disputed), battle axes, or war hammers; their mounts may also have been protected by barding. They were distinct from light cavalry, who were intended for raiding, reconnaissance, screening, skirmishing, patrolling, and tactical communications.

The line formation is a standard tactical formation which was used in early modern warfare. It continued the phalanx formation or shield wall of infantry armed with polearms in use during antiquity and the Middle Ages.

For much of history, humans have used some form of cavalry for war and, as a result, cavalry tactics have evolved over time. Tactically, the main advantages of cavalry over infantry were greater mobility, a larger impact, and a higher riding position.

A gendarme was a heavy cavalryman of noble birth, primarily serving in the French army from the Late Middle Ages to the early modern period. Heirs to the knights of French medieval feudal armies, French gendarmes enjoyed like their forefathers a great reputation and were regarded as the finest European heavy cavalry force until the decline of chivalric ideals largely due to the ever-evolving developments in gunpowder technology. They provided the King of France with a potent regular force of armored lancers which, when properly employed, dominated late medieval and early modern battlefields. Their symbolic demise is generally considered to be the Battle of Pavia, which saw the gendarmes suffer a disastrous defeat and inversely confirmed the rise of the Spanish Tercios as the new dominant military force, leading to the preeminence of the House of Habsburg in 16th century Europe.

Shock tactics, shock tactic, or shock attack is an offensive maneuver which attempts to place the enemy under psychological pressure by a rapid and fully-committed advance with the aim of causing their combatants to retreat. The acceptance of a higher degree of risk to attain a decisive result is intrinsic to shock actions.

The French Imperial Army was the land force branch of the French imperial military during the Napoleonic era.