Carthaginian tombstones are Punic language-inscribed tombstones excavated from the city of Carthage over the last 200 years.

Contents

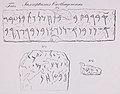

The first such discoveries were published by Jean Emile Humbert in 1817, Hendrik Arent Hamaker in 1828, Christian Tuxen Falbe in 1833 and Thomas Reade in 1837. [3] [4] Between 1817 and 1856, 17 inscriptions were published in total; in 1861 Nathan Davis discovered 73 tablets, marking the first large scale discovery. [5]

The steles were first published together in the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum ; the first focused collection was published by Jean Ferron in 1976. Ferron identified four types of funerary steles: [6]

- Type I: Statues (type I Α, Β or C depending on whether it is a "quasi ronde-bosse", a "half-relief" or a "Herma-type" )

- Type II: Bas-reliefs (Type II 1, where the figure stands out in an arc of a circle, and II 2, where it protrudes in a flattened relief)

- Type III: niche monuments or naiskos (type III 1, with a rectangular or trapezoidal niche, and III 2, niche with triangular top)

- Type IV: Engraved steles (extremely rare).

The oldest funerary stelae belong to Type III and date back to the 5th century BCE, becoming widespread at the end of the 4th century BCE. Bas-reliefs and statues appeared later. [6]