Related Research Articles

The European Convention on Human Rights is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by the then newly formed Council of Europe, the convention entered into force on 3 September 1953. All Council of Europe member states are party to the convention and new members are expected to ratify the convention at the earliest opportunity.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The court hears applications alleging that a contracting state has breached one or more of the human rights enumerated in the convention or its optional protocols to which a member state is a party. The court is based in Strasbourg, France.

Franco Frattini was an Italian politician and magistrate. From January to December 2022, Frattini served as president of the Council of State.

Human rights in Libya is the record of human rights upheld and violated in various stages of Libya's history. The Kingdom of Libya, from 1951 to 1969, was heavily influenced and educated by the British and Y.R.K companies. Under the King, Libya had a constitution. The kingdom, however, was marked by a feudal regime, where Libya had a low literacy rate of 10%, a low life expectancy of 57 years, and 40% of the population lived in shanties, tents, or caves. Illiteracy and homelessness were chronic problems during this era, when iron shacks dotted many urban centres on the country.

Soering v United Kingdom 161 Eur. Ct. H.R. (1989) is a landmark judgment of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) which established that extradition of a German national to the United States to face charges of capital murder and the potential exposure of said citizen to the death row phenomenon violated Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) guaranteeing the right against inhuman and degrading treatment. In addition to the precedent established by the judgment, the judgment specifically resulted in the United States and the State of Virginia committing to not seeking the death penalty against the German national involved in the case, and he was eventually extradited to the United States.

In the European Convention on Human Rights, Article 2 protects the right to life. The article contains a limited exception for the cases of lawful executions and sets out strictly controlled circumstances in which the deprivation of life may be justified. The exemption for the case of lawful executions has been subsequently further restricted by Protocols 6 and 13, for those parties who are also parties to those protocols.

R (Carson) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions and R v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions were a series of civil action court cases seeking judicial review of the British government's policies under the Human Rights Act 1998. They related to the right to property under Article 1 of the First Protocol and prohibition of discrimination under Article 14 of the convention. In Reynolds's case, there was also Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the right to respect for "private and family life" to be considered, as well as Article 3 of the ECHR, the prohibition of torture, and "inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment".

Andrejeva v. Latvia (55707/00) was a case decided by the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights in 2009. It concerned ex parte proceedings and discrimination in calculating retirement pensions for non-citizens of Latvia.

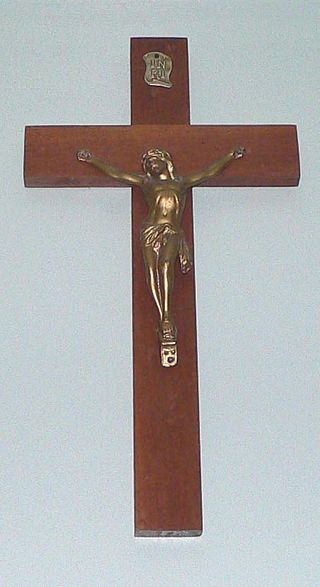

Lautsi v. Italy was a case brought before the European Court of Human Rights, which, on 18 March 2011, ruled that the requirement in Italian law that crucifixes be displayed in classrooms of schools does not violate the European Convention on Human Rights.

Sejdić and Finci v. Bosnia and Herzegovina was a case decided by the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights in December 2009, in the first judgment finding a violation of Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights taken in conjunction with Article 3 of Protocol No. 1 thereof, with regard to the arrangements of the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina in respect of the House of Peoples of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and a violation of Article 1 of Protocol No. 12 with regard to the constitutional arrangements on the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Oršuš and Others v. Croatia (15766/03) was a case heard before the European Court of Human Rights, concerning activities of Roma-only classes in some schools of Croatia, which were held legal by the Constitutional Court of Croatia in 2007 by a decision no. U-III-3138/2002.

Perinçek v. Switzerland is a 2013 judgment of the European Court of Human Rights concerning public statements by Doğu Perinçek, a Turkish nationalist political activist and member of the Talat Pasha Committee, who was convicted by a Swiss court for publicly denying the Armenian genocide. He was sentenced to 90 days in prison and fined 3000 Swiss francs.

Paulo Pinto de Albuquerque is a Portuguese judge born in Beira, Mozambique and was the judge of the European Court of Human Rights in respect of Portugal from April 2011 to March 2020.

Saadi v Italy was a case of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) decided in February 2008, in which the Court unanimously reaffirmed and extended principles established in Chahal v United Kingdom regarding the absolute nature of the principle of non-refoulement and the obligations of a state under Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

In September 1967, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands brought the Greek case to the European Commission of Human Rights, alleging violations of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) by the Greek junta, which had taken power earlier that year. In 1969, the Commission found serious violations, including torture; the junta reacted by withdrawing from the Council of Europe. The case received significant press coverage and was "one of the most famous cases in the Convention's history", according to legal scholar Ed Bates.

Operation HERA is a joint maritime operation by the European Union established to manage migration flows and stop irregular migrants along the Western African Route, from the western shores of Africa to the Canary Islands, Spain. The operation was implemented following an increase in migrants arriving at the Canary Islands in 2006. It remains an annual operation managed by Spain and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (FRONTEX).

Fedotova and Others v. Russia was a case submitted by six Russian nationals to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

Pushback is a term that refers to "a set of state measures by which refugees and migrants are forced back over a border – generally immediately after they crossed it – without consideration of their individual circumstances and without any possibility to apply for asylum". Pushbacks violate the prohibition of collective expulsion of asylum seekers in Protocol 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights and often violate the international law prohibition on non-refoulement.

Sargsyan v. Azerbaijan was an international human rights case regarding the rights of Armenian refugees displaced from former Soviet Azerbaijan because of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. The judgment of the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights on the case originated in an application against the Republic of Azerbaijan lodged with the Court under Article 34 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms by Minas Sargsyan on 11 August 2006. He was forced to flee his home in the village of Gulistan in Shahumyan region of former Soviet Azerbaijan, together with his family, because of the Azerbaijani bombardments of the village and was not allowed to return and unable to get any compensation from the Azerbaijani authorities. Even though the applicant died in 2009, as did his widow, Lena Sargsyan, in 2014, his children, Vladimir and Tsovinar Sargsyan, represented him in court to continue the proceedings.

References

- 1 2 3 4 European Court of Human Rights. "CASE OF HIRSI JAMAA AND OTHERS v. ITALY". ECHR. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 ECHR. "Returning migrants to Libya without examining their case exposed them to a risk of ill-treatment and amounted to a collective expulsion" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ↑ ECHR. "Guide on Article 4 of Protocol No. 4 to the European Convention on Human Rights" (PDF). Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ↑ ECHR. "European Convention on Human Rights" (PDF). Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ↑ Amnesty International (23 February 2012). "Italy: "Historic" European Court judgment upholds migrants' rights". amnesty.org. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch (13 November 2019). "Italy Shares Responsibility for Libya Abuses against Migrants". hrw.org. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ↑ Dembour, Marie-Bénédicte (March 2012). "Interception-at-sea: Illegal as currently practiced – Hirsi and Others v. Italy". strasbourgobservers.com. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ↑ Mann, Itmar (2018). "Maritime Legal Black Holes: Migration and Rightlessness in International Law". The European Journal of International Law. 29 (2): 347–372. doi: 10.1093/ejil/chy029 .

- ↑ Papanicolopulu, Irini (2013). "Hirsi Jamaa v. Italy". The American Journal of International Law. 107 (2): 417–423. doi:10.5305/amerjintelaw.107.2.0417. S2CID 141550999.

- ↑ Holberg, R. K. (2012). "Italy's policy of pushing back african migrants on the high seas rejected by the european court of human rights in the case of hirsi jamaa & others v. italy". Georgetown Immigration Law Journal. 26 (2).