Related Research Articles

The International Criminal Court is an intergovernmental organization and international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to prosecute individuals for the international crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression. The ICC is distinct from the International Court of Justice, an organ of the United Nations that hears disputes between states.

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In the United States, a special counsel is a lawyer appointed to investigate, and potentially prosecute, a particular case of suspected wrongdoing for which a conflict of interest exists for the usual prosecuting authority. Other jurisdictions have similar systems. For example, the investigation of an allegation against a sitting president or attorney general might be handled by a special prosecutor rather than by an ordinary prosecutor who would otherwise be in the position of investigating his or her own superior. Special prosecutors also have handled investigations into those connected to the government but not in a position of direct authority over the Justice Department's prosecutors, such as cabinet secretaries or election campaigns.

International criminal law (ICL) is a body of public international law designed to prohibit certain categories of conduct commonly viewed as serious atrocities and to make perpetrators of such conduct criminally accountable for their perpetration. The core crimes under international law are genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression.

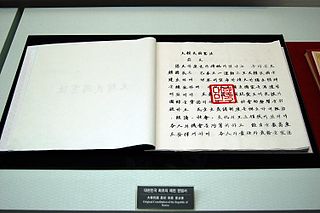

The Constitution of the Republic of Korea is the supreme law of South Korea. It was promulgated on July 17, 1948, and last revised on October 29, 1987.

In the practice of international law, command responsibility is the legal doctrine of hierarchical accountability for war crimes, whereby a commanding officer (military) and a superior officer (civil) is legally responsible for the war crimes and the crimes against humanity committed by his subordinates; thus, a commanding officer always is accountable for the acts of commission and the acts of omission of his soldiers.

The Constitutional Court of Korea is one of the highest courts—along with the Supreme Court—in South Korea's judiciary that exercises constitutional review, seated in Jongno, Seoul. The South Korean Constitution vests judicial power in courts composed of judges, which establishes the ordinary-court system, but also separates an independent constitutional court and grants it exclusive jurisdiction over matters of constitutionality. Specifically, Chapter VI Article 111(1) of the South Korean Constitution specifies the following cases to be exclusively reviewed by the Constitutional Court:

- The constitutionality of a law upon the request of the courts;

- Impeachment;

- Dissolution of a political party;

- Competence disputes between State agencies, between State agencies and local governments, and between local governments; and

- Constitutional complaints as prescribed by [the Constitutional Court] Act.

The Supreme Court of Korea is the highest ordinary court in the judicial branch of South Korea, seated in Seocho, Seoul. Established under Chapter 5 of the Constitution of South Korea, the Court has ultimate and comprehensive jurisdiction over all cases except those cases falling under the jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court of Korea. It consists of fourteen Justices, including the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Korea. The Supreme Court is at the top of the hierarchy of all ordinary courts in South Korea, and traditionally represented the conventional judiciary of South Korea. The Supreme Court has equivalent status as one of the two highest courts in South Korea. The other is the Constitutional Court of Korea.

The legal system of South Korea is a civil law system that has its basis in the Constitution of the Republic of Korea. The Court Organization Act, which was passed into law on 26 September 1949, officially created a three-tiered, independent judicial system. The revised Constitution of 1987 codified judicial independence in Article 103, which states that, "Judges rule independently according to their conscience and in conformity with the Constitution and the law." The 1987 rewrite also established the Constitutional Court, the first time that South Korea had an active body for constitutional review.

Constitution of Nepal 2015 is the present governing Constitution of Nepal. Nepal is governed according to the Constitution which came into effect on 20 September 2015, replacing the Interim Constitution of 2007. The constitution of Nepal is divided into 35 parts, 308 Articles and 9 Schedules.

The law of the Republic of China as applied in Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu is based on civil law with its origins in the modern Japanese and German legal systems. The main body of laws are codified into the Six Codes:

The North Korean judicial system is based on the Soviet model. It includes the Central Court of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Provincial and special-city level Courts, local People's Courts, and Special Courts.

Part Eighteen of the Constitution of Albania is the last of eighteen parts. Titled Transitory and Final Dispositions, it consists of 8 articles.

The National Election Commission is independent constitutional institution in South Korea, established to manage free and fair elections, national referendums and other administrative affairs concerning political parties and funds. The agency was established in accordance with Article 114 of the Constitution of South Korea. The NEC has equal status as highest constitutional institution as National Assembly, the Executive Ministries, the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court. This highly independent status of NEC reflects national will to overcome past histories such as election rigging of South Korea in 1960.

The State Council of the Republic of Korea is the chief executive body and national cabinet of South Korea involved in discussing "important policies that fall within the power of the Executive" as specified by the Constitution. The most influential part of the executive branch of the government of South Korea are the ministries.

The Peaceful Unification Advisory Council is the constitutional organization, established in accordance with the Article 92 of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea and the National Unification Advisory Council Act (Korea) to advise the President of South Korea on the formulation of peaceful unification policy. This had been organized in October 1980.

The Special Investigation Committee of Anti-National Activities was established by the Constituent National Assembly to investigate those who actively cooperated with the Japanese Empire during the Japanese colonial period and conducted viciously anti-ethnic acts. There is one special committee.

Part Ten of the Constitution of Albania is the tenth of eighteen parts. Titled The Office of the Prosecutor, it consists of 13 articles. Together with Part Eight (Constitutional Court), and Part Nine (The Courts) underwent radical changes in 2016 during the so-called Justice Reform, which were the efforts of lawmakers to fight corruption, organized crime, nepotism in the justice system.

Lèse-majesté in Japan was a special crime of defamation concerning the imperial family that was in effect between 1877 and 1947, mostly in militarized Japan. It is an act of disrespect against the imperial family and affiliated sites like imperial shrines and mausoleums. It first appeared in 1877 in the draft of the Japanese Penal Code. Later, it was stipulated in Articles 74 and 76 as one of the elements of the current Penal Code, Part II, Chapter 1, "Crimes against the Imperial Family," which came into effect in 1908. Here, the scope of the crime was extremely wide and any actions considered the act to be disrespectful was enacted. Therefore, this law forced Japanese people to support the Emperor, Shinto, and militaristic Japan during World War II. However, after World War II, in accordance with the strong instructions of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, MacArthur, and the spirit of the new constitution, which respects the equality of individuals, "crimes against the imperial family," including lèse-majesté, were abolished in the 1947 revision of the penal code. Therefore, there is no lèse-majesté in the current law in Japan. During the Meiji and Taisho periods, the number of people who were suspected of lèse-majesté averaged less than ten per year, but during World War II, the number increased dramatically, and from 1941 to 1943, the annual average number rose to nearly 160.

Article 92-6 of South Korea Military Penal Code or Article 92-6 of Republic of Korea Military Criminal Act is a law that punishes anal sex and other indecent acts with imprisonment for not more than two years.

References

- ↑ 中村知子 (Tomoko Nakamura) "韓国における日本大衆文化統制" (Control of Japanese popular culture in Korea) Archived 2011-12-23 at the Wayback Machine (in Japanese). Ritsumeikan University. March 2004. (English translation)

- ↑ "Anti-National Behavior Punishment Act". Korean Law Information Center.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Suzuki, Hitoshi (2004-03-15). "Ban Lifted on Japanese Popular Culture in South Korea". IIST World Forum. Institute for International Studies and Training. Archived from the original on 2004-09-19. Retrieved 2016-07-05.

- ↑ "[어제의 오늘]1998년 일본 대중문화 1차 개방 발표" (in Korean). Kyunghyang Shinmun. 19 October 1998.

- ↑ <연말특집:聯合通信선정 '98 국내 및 해외 10대뉴스>-① (in Korean). yonhapnews. 10 December 1998.

- 1 2 Demick, Barbara (28 December 2003). "South Korea Makes Way for Anime". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved 2016-07-05.

- 1 2 "Minister proposes allowing Japanese dramas into Korea". The Dong-a Ilbo . February 25, 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- 1 2 Kim, Elisa (July 22, 2000). "Korea loosens ban on Japanese pop culture". Billboard . Vol. 112, no. 30. p. 68. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- ↑ "韓国政府による日本文化開放政策(概要)" (Open-door policy of Japanese culture by the Korean government – Overview) (in Japanese), Embassy of Japan in South Korea, 30 December 2003. (English translation)

- ↑ "Kang Minkyung, Dongwoon's 'Udon' single deemed 'unfit' for broadcast". Allkpop .

- ↑ 韓国、日本ドラマ解禁に積極姿勢 (Positive attitude Korea, Japan to ban drama) (in Japanese), 西日本新聞 (West Newspapers), 24 February 2011. (English translation)

- ↑ 日, 정치인까지 反한류 감정에 편승 (Politicians capitalize on the emotions of the Korean Wave) (in Korean), chosun.com, 1 September 2011. (English translation)

- ↑ 「韓流偏重批判に考慮を 自民・片山さつき議員が民放連に要請 ("Liberal Democratic Party lawmaker Satsuki Katayama NAB requested to "take into account the criticism obsessed Hallyu") (in Japanese), J-Cast News, 31 August 2011. (English translation)

- ↑ Yonhap News. <芸能>韓国アイドルの新曲 日本語使用で「放送不適合」 2014/04/03

- ↑ Ashcraft, Brian. "Korean TV Network Bans Pop Song for Using Japanese". Kotaku. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- ↑ "[HD] 140408 Crayon Pop - Uh ee @ SBS MTV The Show". YouTube. Retrieved 2014-04-08.