Rhodesia, officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979. During this fourteen year period Rhodesia served as the de facto successor state to the British colony of Southern Rhodesia, and in 1980 it became modern day Zimbabwe.

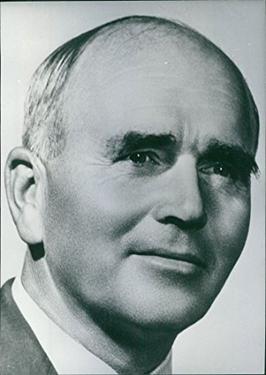

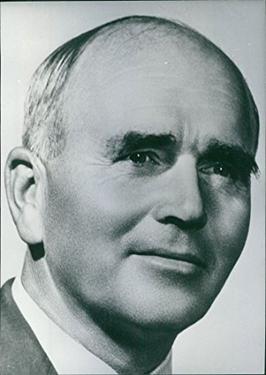

Ian Douglas Smith was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia from 1964 to 1979. He was the country's first leader to be born and raised in Rhodesia, and led the predominantly white government that unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom in November 1965 in opposition to the UK's demands for the implementation of majority rule as a condition for independence. His 15 years in power were defined by the country's international isolation and involvement in the Rhodesian Bush War, which pitted Rhodesia's armed forces against the Soviet- and Chinese-funded military wings of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU).

Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) was a statement adopted by the Cabinet of Rhodesia on 11 November 1965, announcing that Rhodesia a British territory in southern Africa that had governed itself since 1923, now regarded itself as an independent sovereign state. The culmination of a protracted dispute between the British and Rhodesian governments regarding the terms under which the latter could become fully independent, it was the first unilateral break from the United Kingdom by one of its colonies since the United States Declaration of Independence in 1776. The UK, the Commonwealth, and the United Nations all deemed Rhodesia's UDI illegal, and economic sanctions, the first in the UN's history, were imposed on the breakaway colony. Amid near-complete international isolation, Rhodesia continued as an unrecognised state with the assistance of South Africa and Portugal.

The Rhodesian Front (RF) was a conservative political party in Southern Rhodesia, subsequently known as Rhodesia. Formed in March 1962 by white Rhodesians opposed to decolonisation and majority rule, it won that December's general election and subsequently spearheaded the country's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) from the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1965, remaining the ruling party and upholding white minority rule through the majority of the Bush War until 1979. Initially led by Winston Field, the party was led by the majority of its existence by co-founder Ian Smith, who would later go following the end of the Bush War and the country's reconstitution as Zimbabwe, it dissolved in 1981 and was succeeded by the Republican Front.

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second Chimurenga as well as the Zimbabwean War of Liberation, was a civil conflict from July 1964 to December 1979 in the unrecognised country of Rhodesia.

Rhodesia had limited democracy in the sense that it had the Westminster parliamentary system with multiple political parties contesting the seats in parliament, but as the voting was dominated by the White settler minority, and Black Africans only had a minority level of representation at that time, it was regarded internationally as a racist country.

Pieter Kenyon Fleming-Voltelyn van der Byl was a Rhodesian politician who served as his country's Foreign Minister from 1974 to 1979 as a member of the Rhodesian Front (RF). A close associate of Prime Minister Ian Smith, Van der Byl opposed attempts to compromise with the British government and domestic black nationalist opposition on the issue of majority rule throughout most of his time in government. However, in the late 1970s he supported the moves which led to majority rule and internationally recognised independence for Zimbabwe.

General elections were held in Rhodesia on 30 July 1974. They saw the Rhodesian Front of Ian Smith re-elected, once more winning every one of the 50 seats elected by white voters.

The history of Rhodesia from 1965 to 1979 covers Rhodesia's time as a state unrecognised by the international community following the predominantly white minority government's Unilateral Declaration of Independence on 11 November 1965. Headed by Prime Minister Ian Smith, the Rhodesian Front remained in government until 1 June 1979, when the country was reconstituted as Zimbabwe Rhodesia.

Desmond William Lardner-Burke was a politician in Rhodesia.

This article gives an overview of liberal parties in Zimbabwe. It is limited to liberal parties with substantial support, mainly proved by having had a representation in parliament. The sign ⇒ means a reference to another party in that scheme. For inclusion in this scheme it isn't necessary so that parties labeled themselves as a liberal party.

The Southern Rhodesia Communist Party was an illegal, underground communist party established in Southern Rhodesia which was formed in large part due to the minority settler rule, which had an immensely repressive structure. It emerged in 1941 from a split in the Rhodesia Labour Party. The party consisted of a small, and predominantly white, membership. During the parties existence it had links to other communist parties such as the Communist Party of South Africa and the Communist Party of Great Britain. The party disappeared in the late 1940s, with the exact date of its dissolution not being known. Nobel Laureate Doris Lessing author of various works including “The Grass is Singing,” is the most well known member of the Southern Rhodesian Communist Party.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs, commonly referred to as INTAF, was a cabinet ministry of the Rhodesian government. One of Rhodesia's most important governmental departments, it was responsible for the welfare and development of the black African rural population. It played a significant role maintaining control of rural African villages during the Rhodesian Bush War.

William John Harper was a politician, general contractor and Royal Air Force fighter pilot who served as a Cabinet minister in Rhodesia from 1962 to 1968, and signed that country's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) from Britain in 1965. Born into a prominent Anglo-Indian merchant family in Calcutta, Harper was educated in India and England and joined the RAF in 1937. He served as an officer throughout the Second World War and saw action as one of "The Few" in the Battle of Britain, during which he was wounded in action. Appalled by Britain's granting of independence to India in 1947, he emigrated to Rhodesia on retiring from the Air Force two years later.

Lancelot Bales Smith, was an English-born Rhodesian farmer and politician. Elected to Parliament in the 1950s, he was a founding member of Rhodesian Front in 1962. He was Minister without portfolio in the cabinet of Prime Minister Ian Smith at the time of Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965. In 1968, after serving as Deputy Minister of Agriculture, he was appointed Minister of Internal Affairs, a position he held until 1974, when he exited politics.

Ronald Takawira Douglas Sadomba was a Rhodesian politician who served in the House of Assembly from 1970 to 1979. In 1979, he served in the Parliament of the short-lived Rhodesian successor state, Zimbabwe Rhodesia, prior to Zimbabwe's independence. He entered politics as a member of the Centre Party, and changed parties several times, joining throughout his career the African National Council, the United African National Council, ZANU–PF, and United Parties.

David Colville Smith was a farmer and politician in Rhodesia and its successor states, Zimbabwe Rhodesia and Zimbabwe. He served in the cabinet of Rhodesia as Minister of Agriculture from 1968 to 1976, Minister of Finance from 1976 to 1979, and Minister of Commerce and Industry from 1978 to 1979. From 1976 to 1979, he also served Deputy Prime Minister of Rhodesia. He continued to serve as Minister of Finance in the government of Zimbabwe Rhodesia in 1979. In 1980, he was appointed Minister of Trade and Commerce of the newly independent Zimbabwe, one of two whites included in the cabinet of Prime Minister Robert Mugabe.

The Rhodesia Information Centre (RIC), also known as the Rhodesian Information Centre, the Rhodesia Information Service, the Flame Lily Centre and the Zimbabwe Information Centre, represented the Rhodesian government in Australia from 1966 to 1980. As Australia did not recognise Rhodesia's independence, it operated on an unofficial basis.

The Rhodesian government actively recruited white personnel from other countries from the mid-1970s until 1980 to address manpower shortages in the Rhodesian Security Forces during the Rhodesian Bush War. It is estimated that between 800 and 2,000 foreign volunteers enlisted. The issue attracted a degree of controversy as Rhodesia was the subject of international sanctions that banned military assistance due to its illegal declaration of independence and the control which the small white minority exerted over the country. The volunteers were often labelled as mercenaries by opponents of the Rhodesian regime, though the Rhodesian government did not regard or pay them as such.

Rhodesia, was a self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa. Until 1964, the territory was known as Southern Rhodesia, and less than a year before the name change the colony formed a part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland and hosted its capital city, Salisbury. On 1 January 1964, the three parts of the Federation became separate colonies as they had been before the founding of the Federation on 1 August 1953. The demise of the short-lived union was seen as stemming overwhelmingly from black nationalist movements in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, and both colonies were fast-tracked towards independence - Nyasaland first, as Malawi, on 6 July 1964 and Northern Rhodesia second, as Zambia, on 24 October. Southern Rhodesia, by contrast, stood firmly under white government, and its white population, which was far larger than the white populations elsewhere in the erstwhile Federation, was, in general, strongly opposed to the introduction of black majority rule. The Southern Rhodesian prime minister, Winston Field, whose government had won most of the federation's military and other assets for Southern Rhodesia, began to seek independence from the United Kingdom without introducing majority rule. However, he was unsuccessful and his own party, the Rhodesian Front, forced him to resign. Days prior to his resignation, on Field's request, Southern Rhodesia had changed its flag to a sky blue ensign defaced with the Rhodesian coat of arms, becoming the first British colony to use a sky blue ensign instead of a dark blue one.