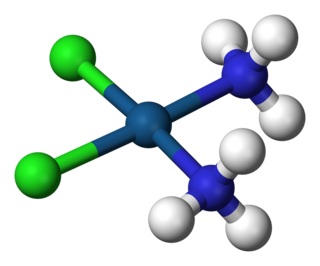

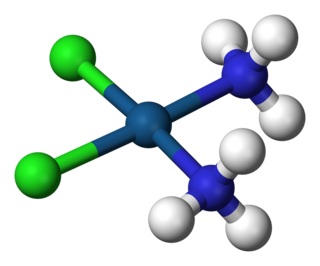

A coordination complex is a chemical compound consisting of a central atom or ion, which is usually metallic and is called the coordination centre, and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions, that are in turn known as ligands or complexing agents. Many metal-containing compounds, especially those that include transition metals, are coordination complexes.

In chemistry, a transition metal is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table, though the elements of group 12 are sometimes excluded. The lanthanide and actinide elements are called inner transition metals and are sometimes considered to be transition metals as well.

The color of chemicals is a physical property of chemicals that in most cases comes from the excitation of electrons due to an absorption of energy performed by the chemical. What is seen by the eye is not the color absorbed, but the complementary color from the removal of the absorbed wavelengths. This spectral perspective was first noted in atomic spectroscopy.

In molecular physics, crystal field theory (CFT) describes the breaking of degeneracies of electron orbital states, usually d or f orbitals, due to a static electric field produced by a surrounding charge distribution. This theory has been used to describe various spectroscopies of transition metal coordination complexes, in particular optical spectra (colors). CFT successfully accounts for some magnetic properties, colors, hydration enthalpies, and spinel structures of transition metal complexes, but it does not attempt to describe bonding. CFT was developed by physicists Hans Bethe and John Hasbrouck van Vleck in the 1930s. CFT was subsequently combined with molecular orbital theory to form the more realistic and complex ligand field theory (LFT), which delivers insight into the process of chemical bonding in transition metal complexes. CFT can be complicated further by breaking assumptions made of relative metal and ligand orbital energies, requiring the use of inverted ligand field theory (ILFT) to better describe bonding.

In organometallic chemistry, the isolobal principle is a strategy used to relate the structure of organic and inorganic molecular fragments in order to predict bonding properties of organometallic compounds. Roald Hoffmann described molecular fragments as isolobal "if the number, symmetry properties, approximate energy and shape of the frontier orbitals and the number of electrons in them are similar – not identical, but similar." One can predict the bonding and reactivity of a lesser-known species from that of a better-known species if the two molecular fragments have similar frontier orbitals, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). Isolobal compounds are analogues to isoelectronic compounds that share the same number of valence electrons and structure. A graphic representation of isolobal structures, with the isolobal pairs connected through a double-headed arrow with half an orbital below, is found in Figure 1.

A flame test, invented by Robert Bunsen, is a qualitative analysis technique used in chemistry to detect the presence of certain elements, primarily metal ions, based on each element's characteristic flame emission spectrum. The color of the flames is understood through the principles of atomic electron transition and photoemission, where varying elements require distinct energy levels (photons) for electron transitions. The color of the flames also generally depends on temperature and oxygen fed; see flame colors. The procedure uses different solvents and flames to view the test flame through a cobalt blue glass to filter the interfering light of contaminants such as sodium. Wooden splints, Nichrome wires, cotton swabs, and melamine foam are suggested for support. Safety precautions are crucial due to the flammability and toxicity of some substances involved. The test provides qualitative data; therefore, obtaining quantitative data requires subsequent techniques like flame photometry or flame emission spectroscopy.

The Laporte rule is a rule that explains the intensities of absorption spectra for chemical species. It is a selection rule that rigorously applies to atoms, and to molecules that are centrosymmetric, i.e. with an inversion centre. It states that electronic transitions that conserve parity are forbidden. Thus transitions between two states that are each symmetric with respect to an inversion centre will not be observed. Transitions between states that are antisymmetric with respect to inversion are forbidden as well. In the language of symmetry, g → g and u → u transitions are forbidden. Allowed transitions must involve a change in parity, either g → u or u → g.

In chemistry, intervalence charge transfer, often abbreviated IVCT or even IT, is a type of charge-transfer band that is associated with mixed valence compounds. It is most common for systems with two metal sites differing only in oxidation state. Quite often such electron transfer reverses the oxidation states of the sites. The term is frequently extended to the case of metal-to-metal charge transfer between non-equivalent metal centres. The transition produces a characteristically intense absorption in the electromagnetic spectrum. The band is usually found in the visible or near infrared region of the spectrum and is broad.

In chemistry, octahedral molecular geometry, also called square bipyramidal, describes the shape of compounds with six atoms or groups of atoms or ligands symmetrically arranged around a central atom, defining the vertices of an octahedron. The octahedron has eight faces, hence the prefix octa. The octahedron is one of the Platonic solids, although octahedral molecules typically have an atom in their centre and no bonds between the ligand atoms. A perfect octahedron belongs to the point group Oh. Examples of octahedral compounds are sulfur hexafluoride SF6 and molybdenum hexacarbonyl Mo(CO)6. The term "octahedral" is used somewhat loosely by chemists, focusing on the geometry of the bonds to the central atom and not considering differences among the ligands themselves. For example, [Co(NH3)6]3+, which is not octahedral in the mathematical sense due to the orientation of the N−H bonds, is referred to as octahedral.

Outer sphere refers to an electron transfer (ET) event that occurs between chemical species that remain separate and intact before, during, and after the ET event. In contrast, for inner sphere electron transfer the participating redox sites undergoing ET become connected by a chemical bridge. Because the ET in outer sphere electron transfer occurs between two non-connected species, the electron is forced to move through space from one redox center to the other.

Copper proteins are proteins that contain one or more copper ions as prosthetic groups. Copper proteins are found in all forms of air-breathing life. These proteins are usually associated with electron-transfer with or without the involvement of oxygen (O2). Some organisms even use copper proteins to carry oxygen instead of iron proteins. A prominent copper proteins in humans is in cytochrome c oxidase (cco). The enzyme cco mediates the controlled combustion that produces ATP.

The 18-electron rule is a chemical rule of thumb used primarily for predicting and rationalizing formulas for stable transition metal complexes, especially organometallic compounds. The rule is based on the fact that the valence orbitals in the electron configuration of transition metals consist of five (n−1)d orbitals, one ns orbital, and three np orbitals, where n is the principal quantum number. These orbitals can collectively accommodate 18 electrons as either bonding or non-bonding electron pairs. This means that the combination of these nine atomic orbitals with ligand orbitals creates nine molecular orbitals that are either metal-ligand bonding or non-bonding. When a metal complex has 18 valence electrons, it is said to have achieved the same electron configuration as the noble gas in the period, lending stability to the complex. Transition metal complexes that deviate from the rule are often interesting or useful because they tend to be more reactive. The rule is not helpful for complexes of metals that are not transition metals. The rule was first proposed by American chemist Irving Langmuir in 1921.

In coordination chemistry, Tanabe–Sugano diagrams are used to predict absorptions in the ultraviolet (UV), visible and infrared (IR) electromagnetic spectrum of coordination compounds. The results from a Tanabe–Sugano diagram analysis of a metal complex can also be compared to experimental spectroscopic data. They are qualitatively useful and can be used to approximate the value of 10Dq, the ligand field splitting energy. Tanabe–Sugano diagrams can be used for both high spin and low spin complexes, unlike Orgel diagrams, which apply only to high spin complexes. Tanabe–Sugano diagrams can also be used to predict the size of the ligand field necessary to cause high-spin to low-spin transitions.

Tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) chloride is the chloride salt coordination complex with the formula [Ru(bpy)3]2+ 2Cl−. This polypyridine complex is a red crystalline salt obtained as the hexahydrate, although all of the properties of interest are in the cation [Ru(bpy)3]2+, which has received much attention because of its distinctive optical properties. The chlorides can be replaced with other anions, such as PF6−.

In X-ray absorption spectroscopy, the K-edge is a sudden increase in x-ray absorption occurring when the energy of the X-rays is just above the binding energy of the innermost electron shell of the atoms interacting with the photons. The term is based on X-ray notation, where the innermost electron shell is known as the K-shell. Physically, this sudden increase in attenuation is caused by the photoelectric absorption of the photons. For this interaction to occur, the photons must have more energy than the binding energy of the K-shell electrons (K-edge). A photon having an energy just above the binding energy of the electron is therefore more likely to be absorbed than a photon having an energy just below this binding energy or significantly above it.

The d electron count or number of d electrons is a chemistry formalism used to describe the electron configuration of the valence electrons of a transition metal center in a coordination complex. The d electron count is an effective way to understand the geometry and reactivity of transition metal complexes. The formalism has been incorporated into the two major models used to describe coordination complexes; crystal field theory and ligand field theory, which is a more advanced version based on molecular orbital theory. However the d electron count of an atom in a complex is often different from the d electron count of a free atom or a free ion of the same element.

Metal L-edge spectroscopy is a spectroscopic technique used to study the electronic structures of transition metal atoms and complexes. This method measures X-ray absorption caused by the excitation of a metal 2p electron to unfilled d orbitals, which creates a characteristic absorption peak called the L-edge. Similar features can also be studied by Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy. According to the selection rules, the transition is formally electric-dipole allowed, which not only makes it more intense than an electric-dipole forbidden metal K pre-edge transition, but also makes it more feature-rich as the lower required energy results in a higher-resolution experiment.

Photochemical reduction of carbon dioxide harnesses solar energy to convert CO2 into higher-energy products. Environmental interest in producing artificial systems is motivated by recognition that CO2 is a greenhouse gas. The process has not been commercialized.

Mixed valence complexes contain an element which is present in more than one oxidation state. Well-known mixed valence compounds include the Creutz–Taube complex, Prussian blue, and molybdenum blue. Many solids are mixed-valency including indium chalcogenides.

Transition metal complexes of 2,2'-bipyridine are coordination complexes containing one or more 2,2'-bipyridine ligands. Complexes have been described for all of the transition metals. Although few have any practical value, these complexes have been influential. 2,2'-Bipyridine is classified as a diimine ligand. Unlike the structures of pyridine complexes, the two rings in bipy are coplanar, which facilitates electron delocalization. As a consequence of this delocalization, bipy complexes often exhibit distinctive optical and redox properties.