Related Research Articles

Coprosma robusta, commonly known as karamu, is a flowering plant in the family Rubiaceae that is endemic to New Zealand. It can survive in many climates, but is most commonly found in coastal areas, lowland forests, or shrublands. Karamu can grow to be around 6 meters tall, and grow leaves up to 12 centimeters long. Karamu is used for a variety of purposes in human culture. The fruit that karamu produces can be eaten, and the shoots of karamu are sometimes used for medical purposes.

Coprosma is a genus of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae. It is found in New Zealand, Hawaiian Islands, Borneo, Java, New Guinea, islands of the Pacific Ocean to Australia and the Juan Fernández Islands.

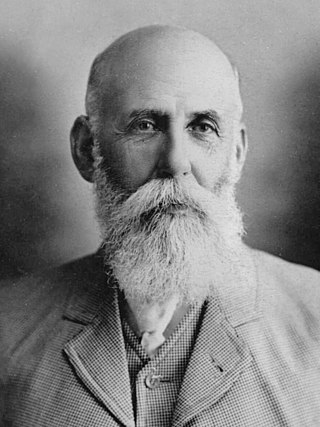

Leonard Cockayne is regarded as New Zealand's greatest botanist and a founder of modern science in New Zealand.

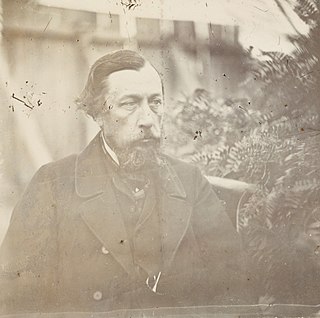

Thomas Frederick Cheeseman was a New Zealand botanist. He was also a naturalist who had wide-ranging interests, such that he even described a few species of sea slugs.

Eric John Godley OBE, FRSNZ, Hon FLS, Hon DSc (Cantuar.), AHRNZIH was a New Zealand botanist and academic biographer. He is best known for his long-running series of in the popular magazine New Zealand Gardener and his "Biographical notes" series that ran in the New Zealand Botanical Society Newsletter and which is the prime resource on the lives of many New Zealand botanists.

Thomas Kirk was an English-born botanist, teacher, public servant, writer and churchman who moved to New Zealand with his wife and four children in late 1862. The New Zealand government commissioned him in 1884 to compile a report on the indigenous forests of the country and appointed him as chief conservator of forests the following year. He published 130 papers in botany and plants including The Durability of New Zealand Timbers, The Forest Flora of New Zealand and Students' Flora of New Zealand.

Mary Sutherland was a notable New Zealand forester and botanist. She was born in London, England in 1893.

Waimate is a town in Canterbury, New Zealand and the seat of Waimate District. It is situated just inland from the eastern coast of the South Island. The town is reached via a short detour west when travelling on State Highway One, the main North/South road. Waimate is 45.7 km south of Timaru, Canterbury's second city, 20 km north of the Waitaki River, which forms the border between Canterbury and the Otago province to the south and 47.5 km north of Oamaru, the main town of the Waitaki District.

Lucy Beatrice Moore was a New Zealand botanist and ecologist.

Elsie Low, was a New Zealand botanist, teacher and temperance campaigner.

Harry Howard Barton Allan was a New Zealand teacher, botanist, scientific administrator, and writer. Despite never receiving a formal education in botany, he became an eminent scientist, publishing over 100 scientific papers, three introductory handbooks on New Zealand plants, and completing the first volume of a flora in his lifetime.

Coprosma fowerakeri is a species of Coprosma found in the South Island of New Zealand described in 2003. It was previously included within C. pseudocuneata.

Thomas Cass was one of New Zealand's pioneer surveyors.

Alick Lindsay Poole was a New Zealand botanist and forester.

Elizabeth Maude Herriott was a New Zealand scientist and academic. She was the first woman appointed to the permanent teaching staff at Canterbury College, now the University of Canterbury.

Raoulia eximia is a species of plant in the family Asteraceae. It was first formally described in 1864 by Joseph Dalton Hooker. It is endemic to New Zealand. The plant is commonly known by its Māori name tutāhuna and as the true vegetable sheep, suggesting its appearance at a distance resembling a sheep.

Leptinella filiformis, or slender button daisy, is a species of flowering plant in the daisy family, found only in the north-eastern part of the South Island of New Zealand. Thought to be extinct by the 1980s, it was rediscovered growing on a Hanmer Springs hotel lawn in 1998, and in the wild in 2015.

Dracophyllum arboreum, commonly known as Chatham Island grass tree and tarahinau (Moriori), is a species of tree in the heath family Ericaceae. Endemic to the Chatham Islands of New Zealand, it reaches a height of 18 m (60 ft) and has leaves that differ between the juvenile and adult forms.

Dracophyllum ophioliticum, commonly known as asbestos inaka and asbestos turpentine tree, is a species of shrub in the family Ericaceae. Endemic to New Zealand, it grows into a sprawling shrub, reaching heights of just 30–200 cm (10–80 in), and has leaves which form bunches at the end of its branches.

Margaret Jane ("Jean") Foweraker née Willis was a New Zealand botanist who specialised in alpine plants- with a particular interest in alpine varieties of crocus- and was a key figure in their popularisation in New Zealand. She was the primary contributor of alpine plants to Christchurch Botanic Gardens, who renamed their Alpine House in recognition of her. She was also author of a series of genealogical works.

References

- ↑ G. R. Macdonald Dictionary of Canterbury Biography, entry F.288, Foweraker, William

- ↑ Threatened Plants of New Zealand, Peter de Lange et al, Canterbury University Press, 2010, p. 199

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, pp. 5-9

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, pp. 5-9

- ↑ The New Zealand University Calendar, Univ. of New Zealand, 1926, p. 247

- ↑ Threatened Plants of New Zealand, Peter de Lange et al, Canterbury University Press, 2010, p. 199

- ↑ Who's who in New Zealand and the Western Pacific, 4th edition, ed. Dr G. H. Scholefield, A. W. Reed Ltd, 1941, pp. 37, 149

- ↑ Annotated summaries of letters to colleagues by the New Zealand botanist Leonard Cockayne– 1, A. D. Thomson, in New Zealand Journal of Botany, vol. 17, 1979, p. 396

- ↑ Notes from the Canterbury College Mountain Biological Station No. 4- the principal plant associations in the immediate vicinity of the station, Leonard Cockayne, Charles E. Foweraker, in Transactions of the New Zealand Institute vol. 48, 1916, pp. 166-186

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, pp. 5-9

- ↑ Annotated summaries of letters to colleagues by the New Zealand botanist Leonard Cockayne– 1, A. D. Thomson, in New Zealand Journal of Botany, vol. 17, 1979, pp. 389-416

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, p. 6

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, pp. 5-9

- ↑ Threatened Plants of New Zealand, Peter de Lange et al, Canterbury University Press, 2010, p. 199

- ↑ Who's who in New Zealand and the Western Pacific, 4th edition, ed. Dr G. H. Scholefield, A. W. Reed Ltd, 1941, pp. 37, 149

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, pp. 5-9

- ↑ Threatened Plants of New Zealand, Peter de Lange et al, Canterbury University Press, 2010, p. 199

- ↑ Who's who in New Zealand and the Western Pacific, 4th edition, ed. Dr G. H. Scholefield, A. W. Reed Ltd, 1941, pp. 37, 149

- ↑ Who's who in New Zealand, 5th edition, ed. Dr G. H. Scholefield, A. H. and A. W. Reed, 1951, p. 81

- ↑ Charles Foweraker: forestry and ideas of sustainability at Canterbury University College (1925-1934), Michael Roche, in ENNZ: Environment and Nature in New Zealand Vol 11, Dec 2018, p. 15

- ↑ Providing Guideline Principles: Botany and Ecology within the State Forest Service of New Zealand during the 1920s, Anton Sveding, in International Review of Environmental History, vol. 5, issue 1, 2019, pp. 113- 128

- ↑ The Rain Forest of Westland, Charles E. Foweraker, in Te Kura Ngahere, vol. 1, 1925, pp. 7-9; The Podocarp Rain Forests of Westland- No. 2. Khaikatea and Totara Forests and Their Relationship to Silting, Charles E. Foweraker, in Te Kura Ngahere, vol. 2, no. 4, 1929, pp. 6-12

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, pp. 5-9

- ↑ Who's who in New Zealand and the Western Pacific, 4th edition, ed. Dr G. H. Scholefield, A. W. Reed Ltd, 1941, pp. 37, 149

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, pp. 5-9

- ↑ Threatened Plants of New Zealand, Peter de Lange et al, Canterbury University Press, 2010, p. 199

- ↑ Who's who in New Zealand and the Western Pacific, 4th edition, ed. Dr G. H. Scholefield, A. W. Reed Ltd, 1941, pp. 37, 149

- ↑ The Plantagenet Roll of the Blood Royal: being a complete table of all the descendants now living of Edward III, King of England: The Clarence Volume, containing the descendants of George, duke of Clarence, Melville de Massue, T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1905, p. 84

- ↑ Threatened Plants of New Zealand, Peter de Lange et al, Canterbury University Press, 2010, p. 199

- ↑ Who's who in New Zealand and the Western Pacific, 4th edition, ed. Dr G. H. Scholefield, A. W. Reed Ltd, 1941, pp. 37, 149

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, pp. 5-9

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, p. 9

- ↑ Annotated summaries of letters to colleagues by the New Zealand botanist Leonard Cockayne– 1, A. D. Thomson, in New Zealand Journal of Botany, vol. 17, 1979, p. 410

- ↑ "Helichrysum fowerakeri Cockayne".

- ↑ "Helichrysum fowerakeri Cockayne - Biota of NZ".

- ↑ Charles E. Foweraker, M.A., F.L.S., botanist and forester, 1886-1964, C. J. Burrows, in Mauri Ora, no. 10, 1982, p. 9

- ↑ A new species of Coprosma (Rubiaceae) from the South Island, New Zealand, D. A. Norton and P. J. de Lange, in New Zealand Journal of Botany, vol. 41, 2003, pp. 223- 231

- ↑ Threatened Plants of New Zealand, Peter de Lange et al, Canterbury University Press, 2010, p. 199