Choe Nam-seon (Korean : 최남선; April 26, 1890 – October 10, 1957), also known by the Japanese pronunciation of his name Sai Nanzen, was a Korean historian, political activist, poet, and publisher who was best remembered as a leading member of the Korean independence movement.

Contents

Early life and education

He was born into a jungin (class between aristocrats and commoners) family in Seoul, Korea, under the late Joseon Dynasty, and educated in Seoul. [1] In 1904 he went to study in Japan, and was greatly impressed by the Meiji Restoration reforms. [2] Upon his return to Korea, Choe became active in the Patriotic Enlightenment Movement, which sought to modernize Korea. [2]

Career

Choe published Korea's first successful modern magazine, Sonyeon (소년;lit. Youth), through which he sought to bring modern knowledge about the world to Korea's youth. [2] He coined the term hangul for the Korean alphabet and promoted it as a literary medium through his magazines. The author of the first “new-style” poem, “From the Ocean to the Youth” (해(海)에게서 소년에게, 1908), he is widely credited with pioneering modern Korean poetry. Choe sought to create a new style of literary Korean that would be more accessible to ordinary people. [2] But at the same time, he was proud of classical Korean literature and he founded the Association of Korea's Glorious Literature in 1910 that sought to encourage ordinary people to read the classics of Korean literature that until then had been mostly read by the elites. [2] Through the work of the Chinese nationalist writer Liang Qichao, Choe learned of the Western theories of Social Darwinism and the idea that history was nothing more than an endless struggle between various people to dominate each other with only the fittest surviving. [3] Choe believed that this competition would only end with Korea ruling the world. [4] In a 1906 essay he wrote:

"How long will it take us to accomplish the goal of flying our sacred national flag above the world and having people of the five continents kneeling down before it? Exert yourselves, our youth!" [3]

Choe's magazine Sonyeon was intended to popularize Western ideas about science and technology though a more readable Korean that would modernize the Korean nation for Social Darwinist competition for world domination. [3] Japan's annexation of Korea in 1910 accelerated the independence movement. Influenced by Social Darwinist theories, Choe urged in numerous articles that the Koreans would have to modernize in order to be strong to survive. [3] In a 1917 article in Hwangsǒng sinmun , Choe wrote:

"The modern age is the age of power in which the powerful survive while the weak perish. This competition continues until death. But why? Because the struggle to be a victor and a survivor never ends. But how? It is a competition of intelligence, physical fitness, material power, economic power, the power of idea and confidence, and of organizational power. Everywhere this competition is underway daily." [3]

Since Korea was annexed by Japan in 1910, for Choe the best way of preserving Korea was giving the Koreans a glorious history that would ensure that the Koreans are at least had the necessary mentality to survive in a harsh world. [5]

In 1919, Choe, together with Choe Rin, organized the March 1st Movement, a non-violent movement to regain Korean sovereignty and independence. For his drafting of the Korean Declaration of Independence, he was arrested by authorities and imprisoned until 1921. In 1928 he joined the Korean History Compilation Committee, which was established by the Governor-General of Korea and commissioned to compile the history of Korea. [6] Here he sought to refute the Japanese imperialist interpretations of ancient Korean history by arguing that ancient Korea was not an impoverished backwater existing in the shadow of Japan, but rather the center of a vibrant civilization. Choe embarked on a re-examination of Korean history. Choe mostly ignored the Samguk Sagi , and instead chose to draw his history from Samguk Yusa , a collection of folktales, stories, and legends, previously disregarded by historians. A major theme of his scholarship was that Korea was always a major center of Asian civilization, instead being in the periphery. [7] Choe claimed in his 1926 book Treatise on Dangun (단군논, Dangunnon) that ancient Korea had outshone both Japan and China. [6] The status of legendary Emperor Dangun as one of the central figures of Korean history was largely due to Choe. [8] Choe did not accept the Tan'gun legend as written, but he argued that the Tan'gun story reflected the shamanistic religion of ancient Korea, and that Dangun was a legendary figure based on a real shaman-ruler who lived sometime in the very distant past. [9] In addition, Choe claimed that civilizations of ancient India, Greece, the Middle East, Italy, northern Europe, and the Mayas all had their origins in the ancient civilization of Korea. [10]

In 1937, Choe started to write articles supporting Japan's aggression against China. [6] In 1939 he became a professor at the Manchukuo Jianguo University. In November 1943, Choe attended the Greater East Asia Conference in Tokyo, which was intended by the Japanese government to mobilize support for the war throughout Asia for its Pan-Asian war goals. [11] During the conference, Choe delivered a speech to a group of Korean students studying in Japan calling the "Anglo-Saxon" powers Britain and America the most deadly enemies of Asians everywhere, and urged the students to do everything in their power to support the war against the "Anglo-Saxons", saying that there was no higher honor for a Korean than to die fighting for Japan's efforts to create the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere". [11] During his speech, Choe praised Japanese imperialism and stated that the Koreans were fortunate to be colonized by Japan. [12] Choe also claimed that originally Korean culture had been violent and militaristic much like Japanese culture, but then had gone "soft" under Chinese influence. [11] Furthermore, Choe suggested that his historical research had established that the Japanese were the descendants of immigrants from Korea, and the samurai being of Korean descent had preserved the true, violent essence of ancient Korean culture. [11] The South Korean historian Kyung Moon Hwang wrote that there is a striking contrast between Choe, the passionate patriot who penned the Declaration of Independence in 1919 vs. Choe, the Chinilpa collaborator of 1943 urging Korean university students to enlist in the Imperial Japanese Army and die for the Emperor of Japan. [12] Kyung suggested that the change in Choe was caused by the fact that Japan had occupied Korea in 1904 during the Russian-Japanese War and by the early 1940s, the "permanence" of Japanese rule was assumed by most Koreans as every attempt to win independence had always ended in failure. [12] Given this situation, Koreans like Choe had lost their youthful idealism and abandoned their dreams of freedom, simply hoping to reach an accommodation with the Japanese that might at least preserve some sort of Korean cultural identity. [12]

In 1949, Syngman Rhee’s government arrested Choe for collaboration with the Japanese during the colonial period, but he was released when the trial was suspended. During the Korean War, Choe served on the Naval History Committee; after the war, he served on the Seoul City History Committee. He died in October 1957 after struggles with diabetes and hypertension. Choe remains a deeply controversial figure in Korea today, being respected for his historical work and his efforts to create the modern Korean language while being condemned for his wartime statements supporting Japan. [12]

Representative works

In addition to a large body of historical works, Choe’s writings range from poetry, song lyrics, travelogues, to literary, social, and cultural criticism. His representative books include:

- The History of Chosŏn (1931)

- The Encyclopedia of Korean History (1952)

- The Annotated Samgukyusa (1940)

- Simchun Sulle (The Pilgrimage in Search of Spring, 1925)

- Paektusan Kunchamgi (The Travels to Paektu Mountain, 1926)

- Kumkang Yechan (A Paean to Kumgang, 1928)

- Paekpal Ponnoe (One-Hundred-and-Eight Agonies, 1926)

- Kosatong (A Collection of Ancient Stories, 1943)

- Simundokpon (A Reader of Modern Writing, 1916)

See also

Related Research Articles

The Lower Paleolithic era on the Korean Peninsula and in Manchuria began roughly half a million years ago. The earliest known Korean pottery dates to around 8000 BC, and the Neolithic period began after 6000 BC, followed by the Bronze Age by 2000 BC, and the Iron Age around 700 BC. Similarly, according to The History of Korea, the Paleolithic people are not the direct ancestors of the present Korean people, but their direct ancestors are estimated to be the Neolithic People of about 2000 BC.

Jizi, Qizi, or Kizi was a semi-legendary Chinese sage who is said to have ruled Gija Joseon in the 11th century BCE. Early Chinese documents like the Book of Documents and the Bamboo Annals described him as a virtuous relative of the last king of the Shang dynasty who was punished for remonstrating with the king. After Shang was overthrown by Zhou in the 1040s BCE, he allegedly gave political advice to King Wu, the first Zhou king. Chinese texts from the Han dynasty onwards claimed that King Wu enfeoffed Jizi as ruler of Chaoxian. According to the Book of Han, Jizi brought agriculture, sericulture, and many other facets of Chinese civilization to Joseon. His family name was Zi/Ja (子) and given name was Xuyu/Suyu.

Dangun or Tangun, also known as Dangun Wanggeom, was the legendary founder and god-king of Gojoseon, the first Korean kingdom. He founded the kingdom around present-day Liaoning province in Northeast China and the northern part of the Korean Peninsula. He is said to be the "grandson of heaven", "son of a bear", and to have founded the kingdom in 2333 BC. The earliest recorded version of the Dangun legend appears in the 13th-century Samguk Yusa, which cites Korea's lost historical record, Gogi and China's Book of Wei.

The Three Kingdoms of Korea or Samguk competed for hegemony over the Korean Peninsula during the ancient period of Korean history. During the Three Kingdoms period, many states and statelets consolidated until, after Buyeo was annexed in 494 and Gaya was annexed in 562, only three remained on the Korean Peninsula: Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla. The "Korean Three Kingdoms" contributed to what would become Korea; and the Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla peoples became the Korean people.

Samguk yusa or Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms is a collection of legends, folktales and historical accounts relating to the Three Kingdoms of Korea, as well as to other periods and states before, during and after the Three Kingdoms period. "Samguk yusa is a historical record compiled by the Buddhist monk Il-yeon in 1281 in the late Goryeo Dynasty." It is the earliest extant record of the Dangun legend, which records the founding of Gojoseon as the first Korean nation. The Samguk yusa is National Treasure No. 306.

Gojoseon, also called Joseon, was the first kingdom on the Korean Peninsula. According to Korean mythology, the kingdom was established by the legendary king Dangun. Gojoseon possessed the most advanced culture in the Korean Peninsula at the time and was an important marker in the progression towards the more centralized states of later periods. The addition of Go, meaning "ancient", is used in historiography to distinguish the kingdom from the Joseon dynasty, founded in 1392 CE.

Gija Joseon was a dynasty of Gojoseon allegedly founded by the sage Jizi (Gija), a member of the Shang dynasty royal house. Concrete evidence for Jizi's role in the history of Gojoseon is lacking, and the narrative has been challenged since the 20th century.

Heo Hwang-ok also known as Empress Boju, was a legendary queen mentioned in Samguk yusa, a 13th-century Korean chronicle. According to Samguk Yusa, she became the wife of King Suro of Geumgwan Gaya at the age of 16, after having arrived by boat from a distant kingdom called "Ayuta". Her native kingdom is believed to be located in India. There is a tomb in Gimhae, South Korea, that is believed to be hers, and a memorial in Ayodhya, India built in 2020. The Ayuta Kingdom is a misinterpretation of the Ay Kingdom, a vassal to the Pandyan Empire of ancient Tamilakam as some sources allude to her coming from the southern part of India,

Ch'oe Ch'i-wŏn was a Korean philosopher and poet of the late medieval Unified Silla period (668-935). He studied for many years in Tang China, passed the Tang imperial examination, and rose to the high office there before returning to Silla, where he made ultimately futile attempts to reform the governmental apparatus of a declining Silla state.

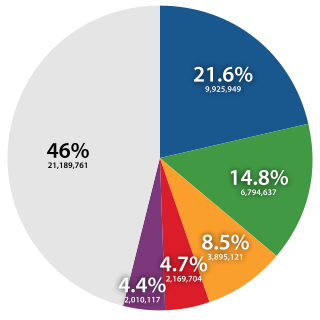

Choi is a Korean family surname. As of the South Korean census of 2015, there were around 2.3 million people by this name in South Korea or roughly 4.7% of the population. In English-speaking countries, it is most often anglicized as Choi, and sometimes also Chey, Choe or Chwe. Ethnic Koreans in the former USSR prefer the form Tsoi (Tsoy) especially as a transcription of the Cyrillic Цой.

Shin Chae-ho, or Sin Chaeho, was a Korean independence activist, historian, anarchist, nationalist, and a founder of Korean nationalist historiography. He is held in high esteem in both North and South Korea.

Hwanguk is the first mythical state of Korea claimed to have existed according to Hwandan Gogi. According to Hwandan Gogi, Hwanguk existed long before Gojoseon. However, mainstream Korean historians reject the existence of Hwanguk for lack of credible evidence.

Prehistoric Korea is the era of human existence in the Korean Peninsula for which written records do not exist. It nonetheless constitutes the greatest segment of the Korean past and is the major object of study in the disciplines of archaeology, geology, and palaeontology.

Daejongism and Dangunism are the names of a number of religious movements within the framework of Korean shamanism, focused on the worship of Dangun. There are around seventeen of these groups, the main one of which was founded in Seoul in 1909 by Na Cheol (1864–1916).

Anarchism in Korea dates back to the Korean independence movement in Korea under Japanese rule (1910-1945). Korean anarchists federated across their end of the continent, including forming groups on the Japanese mainland and in Manchuria, but their efforts were perforated by regional and world wars.

The Greater East Asia Conference was an international summit held in Tokyo from 5 to 6 November 1943, in which the Empire of Japan hosted leading politicians of various component parts of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The event was also referred to as the Tokyo Conference.

The history of Sino-Korean relations dates back to prehistoric times.

Choe Ik-hyeon was a Korean Joseon Dynasty scholar, politician, philosopher, and general of the Korean Righteous Army guerrilla forces. He was a strong supporter of Neo-Confucianism and a very vocal nationalist, who defended Korean sovereignty in the face of Japanese imperialism.

Korean nationalist historiography is a way of writing Korean history that centers on the Korean minjok, an ethnically defined Korean nation. This kind of nationalist historiography emerged in the early twentieth century among Korean intellectuals who wanted to foster national consciousness to achieve Korean independence from Japanese domination. Its first proponent was journalist and independence activist Shin Chaeho (1880–1936). In his polemical New Reading of History, which was published in 1908 three years after Korea became a Japanese protectorate, Shin proclaimed that Korean history was the history of the Korean minjok, a distinct race descended from the god Dangun that had once controlled not only the Korean peninsula but also large parts of Manchuria. Nationalist historians made expansive claims to the territory of these ancient Korean kingdoms, by which the present state of the minjok was to be judged.

Korean historiography is the way of writing Korean history. The historiography of Korea has evolved over time, reflecting specific periods and cultural contexts, leading to a better understanding of Korean history. During the Joseon Dynasty, historical narratives were influenced by the perspective of the royal court, emphasizing a state-centric view. However, through the independence movement and the Japanese colonial period, Korean historiography shifted towards a more realistic analysis and critical thinking. Modern Korean historiography attempts to offer multi-dimensional understanding through independent perspectives, diverse theories, and methodologies, highlighting the comparative characteristics and significance of Korean history.

References

- ↑ Choi, Hak Joo (2012-07-01). "Yuktang Ch'oe Nam-son and Korean Modernity". YBM, Inc. ISBN 978-8917214338.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Allen 1990, p. 787.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Allen 1990, p. 789.

- ↑ Allen 1990, p. 790.

- ↑ Allen 1990, p. 791.

- 1 2 3 Allen 1990, p. 788.

- ↑ Hwang 2010, p. 177.

- ↑ Allen 1990, p. 794.

- ↑ Allen 1990, p. 795.

- ↑ Allen 1990, p. 799.

- 1 2 3 4 Hwang 2010, p. 191.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hwang 2010, p. 192.

Sources

- Allen, Chizuko T. (1990). "Northeast Asia Centered Around Korea: Ch'oe Namsŏn's View of History". The Journal of Asian Studies. 49 (4): 787–806. doi:10.2307/2058236. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2058236.

- Hwang, Kyung Moon (2010-10-15). A History of Korea. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-20545-1.

| Choe Nam-seon | |

|

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Academics | |

| Other | |