Related Research Articles

The cinema of Italy comprises the films made within Italy or by Italian directors. Since its beginning, Italian cinema has influenced film movements worldwide. Italy is one of the birthplaces of art cinema and the stylistic aspect of film has been one of the most important factors in the history of Italian film. As of 2018, Italian films have won 14 Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film as well as 12 Palmes d'Or, one Academy Award for Best Picture and many Golden Lions and Golden Bears.

Cesare Zavattini was an Italian screenwriter and one of the first theorists and proponents of the Neorealist movement in Italian cinema.

Italian neorealism, also known as the Golden Age, was a national film movement characterized by stories set amongst the poor and the working class. They are filmed on location, frequently with non-professional actors. They primarily address the difficult economic and moral conditions of post-World War II Italy, representing changes in the Italian psyche and conditions of everyday life, including poverty, oppression, injustice and desperation.

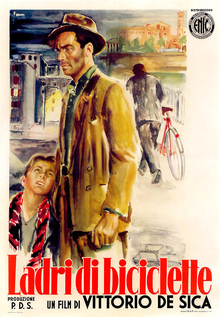

Bicycle Thieves, also known as The Bicycle Thief is a 1948 Italian neorealist drama film directed by Vittorio De Sica. It follows the story of a poor father searching in post-World War II Rome for his stolen bicycle, without which he will lose the job which was to be the salvation of his young family.

Filmfare is an Indian English-language fortnightly magazine published by Worldwide Media. Acknowledged as one of India's most popular entertainment magazines, it publishes pieces involving news, interviews, photos, videos, reviews, events, and style. The magazine also annually gives the Filmfare Awards, the Filmfare Awards South, the Filmfare Awards East, the Filmfare Marathi Awards, the Filmfare Awards Punjabi, the Filmfare OTT Awards, the Filmfare Short Film Awards, and the Filmfare Style & Glamour Awards.

La strada is a 1954 Italian drama film directed by Federico Fellini and co-written by Fellini, Tullio Pinelli and Ennio Flaiano. The film tells the story of Gelsomina, a simple-minded young woman bought from her mother by Zampanò, a brutish strongman who takes her with him on the road.

Robert Anthony Sklar was an American historian and author specializing in the history of cinema.

Miracle in Milan is a 1951 Italian fantasy film directed by Vittorio De Sica. The screenplay was co-written by Cesare Zavattini, based on his novel Totò il Buono. The picture stars Francesco Golisano, Emma Gramatica, Paolo Stoppa, and Guglielmo Barnabò.

The White Sheik is a 1952 Italian romantic comedy film directed by Federico Fellini and starring Alberto Sordi, Leopoldo Trieste, Brunella Bovo and Giulietta Masina. Written by Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio Flaiano and Michelangelo Antonioni, the film is about a man who brings his new bride to Rome for their honeymoon, to have an audience with the Pope, and to present his wife to his family. When the young woman sneaks away to find the hero of her romance novels, the man is forced to spend hour after hour making excuses to his eager family who want to meet his missing bride. The White Sheik was filmed on location in Fregene, Rome, Spoleto and Vatican City.

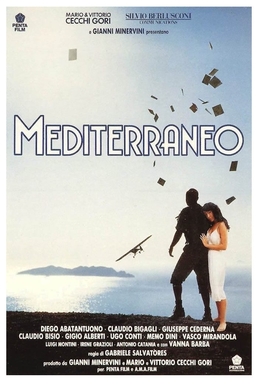

Mediterraneo is a 1991 Italian war comedy-drama film directed by Gabriele Salvatores and written by Enzo Monteleone. The film is set during World War II and concerns a group of Italian soldiers who become stranded on a Greek island in the Aegean Sea, and are left behind by the war. It won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1992.

Renato Castellani was an Italian film director and screenwriter.

Bianco e Nero is an Italian film journal. It is the oldest film publication in Italy.

The International Film Festival of India (IFFI), founded in 1952, is one of the film festivals in Asia. Held annually, currently in the state of Goa, on the western coast of the country, the festival aims at providing a common platform for the cinemas of the world to project the excellence of the film art; contributing to the understanding and appreciation of film cultures of different nations in the context of their social and cultural ethos, and promoting friendship and cooperation among people of the world. The festival is conducted jointly by the National Film Development Corporation of India and the state Government of Goa.

The Sun Still Rises also known as Outcry is a 1946 Italian neorealist war-drama film directed by Aldo Vergano and starring Elli Parvo, Massimo Serato and Lea Padovani.

Giannalberto Bendazzi was an Italian animation historian, author, and professor.

Hamid Naficy is an Iranian-born American filmmaker, writer, scholar, and educator. He is the Hamad Bin Khalifa Al-Thani Professor in Communication at Northwestern University in the department of Radio/Film/Television, an affiliate faculty member in the Department of Art History, and a core member of the Middle East and North African Studies Program.

Guido Aristarco was an Italian film critic and author.

Daniele Vicari is an Italian director, screenwriter and producer.

Objetivo was a film magazine published between 1953 and 1955 in Madrid, Spain. The magazine was one of the significant publications, which contributed to the struggle for a censorship-free cinema in Francoist Spain. Spanish author Marvin D'Lugo argues that the magazine was very influential during its lifetime despite its short existence and lower levels of circulation.

Filmic representations of women have developed in tandem with changing historical and socio-cultural influences. Italian neorealism was a movement that, through art and film, attempted to "[recover] the reality of Italy" for an Italian society that was disillusioned by the propaganda of fascism. Representations of women in this era were influenced heavily by the suffrage movement and changing socio-political awareness of gender rights. The tension of this transitional era created a spectrum of female representation in film, where female characters were written to acquiesce, or more commonly reject, the societal standards imposed on the women of the age. Italian neorealists, with their characteristic use of realism and thematic-driven narrative, used their medium to explore these established ideals of gender and produce a number of filmic representations of women.

References

- 1 2 "Guido Aristarco". Good Reads . Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- 1 2 Fernando Ramos Arenas (Spring 2012). "Writing about a Common Love for Cinema: Discourses of Modern Cinephilia as a trans-European Phenomenon" (PDF). Trespassing Nation (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marco Pistoia (2003). "Cinema nuovo". Enciclopedia del Cinema (in Italian).

- ↑ Rosanna Maule (2008). Beyond Auteurism: New Directions in Authorial Film Practices in France, Italy and Spain since the 1980s. Bristol; Chicago: Intellect Books. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-84150-204-5.

- ↑ Saverio Giovacchini (2011). "Living peace after the massacre: Neorealism, colonialism and race". In Saverio Giovacchini; Robert Sklar (eds.). Global Neorealism: The Transnational History of a Film Style. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-61703-123-6.

- ↑ Maria Antonella Pelizzari (2012). "Un Paese (1955) and the Challenge of Mass Culture". Études photographiques (30).

- ↑ Jeffrey Middents (2009). Writing National Cinema: Film Journals and Film Culture in Peru. Hanover; London: UPNE. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-58465-776-7.

- ↑ Esteve Riambau (2014). "The clandestine militant who would be minister: Semprún and cinema". In O. Ferrán; G. Herrmann (eds.). A Critical Companion to Jorge Semprún: Buchenwald, Before and After. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-137-43971-0.

- ↑ Marvin D'Lugo (1991). The Films of Carlos Saura: The Practice of Seeing . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-691-00855-8.