Related Research Articles

The Jackson–Vanik amendment to the Trade Act of 1974 is a 1974 provision in United States federal law intended to affect U.S. trade relations with countries with non-market economies that restrict freedom of Jewish emigration and other human rights. The amendment is contained in the Trade Act of 1974 which passed both houses of the United States Congress unanimously, and was signed by President Gerald Ford into law, with the adopted amendment, on January 3, 1975. Over time, a number of countries were granted conditional normal trade relations subject to annual review, and a number of countries were liberated from the amendment.

Soviet anti-Zionism is an anti-Zionist and pro-Arab doctrine promulgated in the Soviet Union during the Cold War. While the Soviet Union initially pursued a pro-Zionist policy after World War II due to its perception that the Jewish state would be socialist and pro-Soviet, its outlook on the Arab–Israeli conflict changed as Israel began to develop a close relationship with the United States and aligned itself with the Western Bloc.

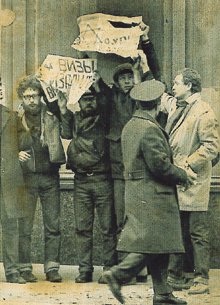

Refusenik was an unofficial term for individuals—typically, but not exclusively, Soviet Jews—who were denied permission to emigrate, primarily to Israel, by the authorities of the Soviet Union and other countries of the Soviet Bloc. The term refusenik is derived from the "refusal" handed down to a prospective emigrant from the Soviet authorities.

The Canadian Jewish Congress was, for more than ninety years, the main advocacy group for the Jewish community in Canada. Regarded by many as the "Parliament of Canadian Jewry," the Congress was at the forefront of the struggle for human rights, equality, immigration reform and civil rights in Canada.

Union of Councils for Jews in the Former Soviet Union (UCSJ) is a non-governmental organization that reports on the human rights conditions in countries throughout Eastern Europe and Central Asia, exposing hate crimes and assisting communities in need. UCSJ uses grassroots-based monitoring and advocacy, as well as humanitarian aid, to protect the political and physical safety of Jewish people and other minorities in the region. UCSJ is based in Washington, D.C., and is linked to other organizations such as the Moscow Helsinki Group. It has offices in Russia and Ukraine and has a collegial relationship with human rights groups that were founded by the UCSJ in the countries of the former Soviet Union.

The Jewish Labor Committee (JLC) is an American secular Jewish labor organization founded in 1934 to oppose the rise of Nazism in Germany. Among its central purposes is promoting labor union interests in the organized Jewish communities, especially in the USA, and Jewish interests within U.S. labor unions. The organization is headquartered in New York City, where it was founded, with local/regional offices in Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago and Los Angeles, and volunteer-led affiliated groups in other U.S. communities. Today, it works to maintain and strengthen the historically strong relationship between the American Jewish community and the trade union movement, and to promote what they see as the shared social justice agenda of both communities. The JLC was also active in Canada from 1936 until the 1970s.

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term dissident was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960s until the Fall of Communism. It was used to refer to small groups of marginalized intellectuals whose challenges, from modest to radical to the Soviet regime, met protection and encouragement from correspondents, and typically criminal prosecution or other forms of silencing by the authorities. Following the etymology of the term, a dissident is considered to "sit apart" from the regime. As dissenters began self-identifying as dissidents, the term came to refer to an individual whose non-conformism was perceived to be for the good of a society. The most influential subset of the dissidents is known as the Soviet human rights movement.

Jacob (Yaakov) Birnbaum was the German-born founder of Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry (SSSJ) and other human rights organizations. Because the SSSJ, at the time of its founding, in 1964, was the first initiative to address the plight of Soviet Jewry, he is regarded as the father of the Movement to Free Soviet Jewry. His father was Solomon Birnbaum and grandfather Nathan Birnbaum.

The Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, also known by its acronym SSSJ, was founded in 1964 by Jacob Birnbaum to be a spearhead of the U.S. movement for rights of the Jews in the Soviet Union. The organisation held demonstrations, at various important locations.

The 1970s Soviet Union aliyah was the mass immigration of Soviet Jews to Israel after the Soviet Union lifted its ban on Jewish refusenik emigration in 1971. More than 150,000 Soviet Jews immigrated during this period, motivated variously by religious or ideological aspirations, economic opportunities, and a desire to escape anti-Semitic discrimination.

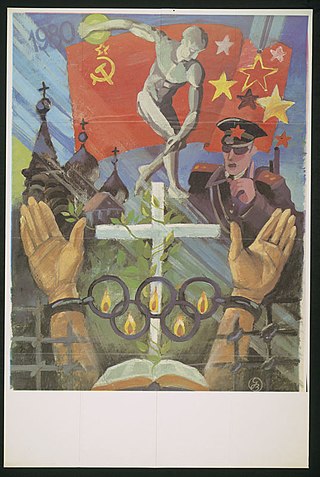

The Soviet Jewry movement was an international human rights campaign that advocated for the right of Jews in the Soviet Union to emigrate. The movement's participants were most active in the United States and in the Soviet Union. Those who were denied permission to emigrate were often referred to by the term Refusenik.

The February Revolution in Russia officially ended a centuries-old regime of antisemitism in the Russian Empire, legally abolishing the Pale of Settlement. However, the previous legacy of antisemitism was continued and furthered by the Soviet state, especially under Joseph Stalin. After 1948, antisemitism reached new heights in the Soviet Union, especially during the anti-cosmopolitan campaign, in which numerous Yiddish-writing poets, writers, painters and sculptors were arrested or killed. This campaign culminated in the so-called Doctors' plot, in which a group of doctors were subjected to a show trial for supposedly having plotted to assassinate Stalin. Although repression eased after Stalin's death, persecution of Jews would continue until the late 1980s.

The National Coalition Supporting Eurasian Jewry (NCSEJ), formerly the National Council for Soviet Jewry (NCSJ), is an organization in the United States which advocates for the freedoms and rights of Jews in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltic States, and Eurasia. Emerging from the American Jewish Conference on Soviet Jewry, now with a paid staff, it played an important role in the Soviet Jewry movement, including such landmark legislation as Jackson–Vanik amendment. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., it is now an umbrella organization of about 50 national organizations and 300+ local federations, community councils and committees.

Freedom Sunday for Soviet Jews was the title of a national march and political rally that was held on December 6, 1987 in Washington, D.C. An estimated 200,000 participants gathered on the National Mall, calling for the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, to extend his policy of Glasnost to Soviet Jews by putting an end to their forced assimilation and allowing their emigration from the Soviet Union. The rally was organized by a broad-based coalition of Jewish organizations. At the time, it was reported to be the "largest Jewish rally ever held in Washington."

Pamela Braun Cohen is an activist in the American Soviet Jewry movement. She began her activist work in the Chicago Action for Soviet Jewry in the 1970s and served as the national president of the Union of Councils for Soviet Jews (UCSJ) from 1986-1997.

David Jonathan Waksberg, was a leading activist in the Soviet Jewry Movement during the 1980s and early 1990s. In the 1970s he became involved in the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. In the early 1980s he moved to California and began working for the Bay Area Council for Soviet Jews, first as Assistant Director, and later as executive director. He initiated public and political activities on behalf of Soviet Jewry, supervised research and monitoring of their welfare and coordinated financial, medical and legal aid to Refuseniks and Prisoners of Conscience trapped in the Soviet Union. During his first visit to the USSR in 1982, Waksberg was arrested and detained by the KGB while attempting, along with refusenik Yuri Chernyak, to visit Kiev refusenik Lev Elbert. He organized numerous protest demonstrations and vigils to raise public awareness of the plight of Jews in the USSR. In 1985 Waksberg became National Vice-President of BACSJ's umbrella organization, the Union of Councils for Soviet Jews. Waksberg frequently visited Jewish communities of the Soviet Union and the former Soviet states and coordinated briefings of the American travelers interested in visiting those communities. In 1990 Waksberg took on the role of Director of the Center for Jewish Renewal, newly established by UCSJ. The mission of the CJR was to promote the renewal and development of Jewish life in the USSR and the emigration rights, human rights and resettlement needs of Jews in the Former Soviet Union. The CJR established a network of human rights and emigration bureaus in major cities of the former Soviet Union. In mid-1990s Waksberg was a member of Bay Area Council's Board of Directors and served as Director of Development and Communication of the UCSJ. Since 2007 Waksberg has served as Chief Executive Officer of Jewish LearningWorks.

The Bay Area Council for Soviet Jews (BACSJ) was founded in 1967 by Harold B. Light, Edward Tamler, Sidney Kluger, and Rabbi Moris Hershman as a grassroots human rights organization with a mission to advocate for Soviet Jewry's freedom of religion and the right to emigrate to Israel. BACSJ was one of the largest and most active local grassroots organizations in the American Soviet Jewry movement. BACSJ was a member of the Union of Councils for Soviet Jews (UCSJ), an umbrella institution for approximately 50 organizations working on behalf of Jews in the USSR. After the fall of the Soviet Union BACSJ was renamed Bay Area Council for Jewish Rescue and Renewal and shifted its focus to monitoring the human rights conditions in countries throughout Eastern Europe and Central Asia and assisting former Soviet Jewish communities in need.

Louis Rosenblum was a pioneer in the movement for freedom of emigration for the Jews in the Soviet Union, was a founder of the first organization to advocate for the freedom of Soviet Jews, the Cleveland Council on Soviet Anti-Semitism, founding president of the Union of Councils for Soviet Jews, and a research scientist at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Lewis Research Center.

Alexander Smukler is a Soviet-born American businessman, who is the chairman of the board of Agroterminal LTD and the chairman of the board of Century 21: Russia, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine. He is a former managing partner of Ariel Investment Group, which develops commercial enterprises and civil engineering projects in Russia.

Soviet Jews in America or American Soviet Jews are Jews from former Soviet Republics that have emigrated to the United States. The group consists of people that are Jewish by religion, ethnicity, culture, or nationality, that have been influenced by their collective experiences in the Soviet Union. In the 60s, there were around 2.3 million Jews in the USSR, as ethnicity was recorded in the census. Jews from the Soviet Union consisted mostly of the Ashkenazi sect, and emigrated in waves starting in the 1960s, with over 200,000 leaving in the 1970s. As of 2005, over 500,000 Jews had left Soviet Republics for the United States. American Soviet Jews are often covered by the blanket term, "Russian-speaking Jews", and are a self-selecting group, due to the barriers that people leaving the USSR had to face. Often-times, Soviet immigrants struggle with the abundance of choices that they can make in America, but after learning the language, have been shown to be as well-adjusted as other immigrant groups.

References

- 1 2 Peretz, Pauline (2017). Let My People Go: The Transnational Politics of Soviet Jewish Emigration During the Cold War. Routledge. p. 117 ff. ISBN 9781351508902.

- 1 2 Friedman, Murray (1999). A Second Exodus: The American Movement to Free Soviet Jews. University Press of New England. p. 32. ISBN 9780874519136 . Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- 1 2 3 ORBACH, WILLIAM, and ויליאם אורבך. “התפתחויות רעיוניות בתנועה למען יהדות ברית-המועצות / CONFLICTS AND DEVELOPMENTS WITHIN THE SOVIET JEWRY MOVEMENT.” Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies / דברי הקונגרס העולמי למדעי היהדות, ט, 1985, pp. 389–396. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23529453.

- ↑ Golden, Peter (2012). O Powerful Western Star!: American Jews, Russian Jews, and the Final Battle of the Cold War. Gefen Publishing. p. 183 ff. ISBN 9789652295439.