Establishment

Prior to 1865 (and until 1905), Law enforcement in Pennsylvania existed only on the county level or below; an elected sheriff was the primary law enforcement officer (for each county). With the construction of the railroad, the Pennsylvania hinterlands were opened up to development. As mining and coal-powered industries like iron and steel manufacturing expanded, Coal, railroad and iron operators made the case that they required additional protection of their property. Thus the Pennsylvania State Legislature passed State Act 228. This empowered the railroads to organize private police forces. In 1866, a supplement to the act was passed extending the privilege to "embrace all corporations, firms, or individuals, owning, leasing, or being in possession of any colliery, furnace, or rolling mill within this commonwealth". The 1866 supplement also stipulated that the words "coal and iron police" appear on their badges. [2] For one dollar each, the state sold to the mine and steel mill owners commissions conferring police power upon whoever the owners selected. [3] A total of 7,632 commissions were given for the Coal and Iron Police. In 1871, Governor John White Geary instituted a $1 fee for each C&I commission. Prior to that, there was no cost associated with obtaining the legal right to hire a private policeman. [1]

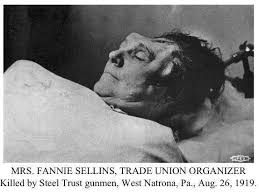

Although the Coal and Iron Police nominally existed solely to protect company property, in practice the companies used them as strikebreakers, and to coerce and discipline workers and their families. [4] C&Is were sometimes used to crack down on unemployed miners and the families of miners' practice of "bootlegging" or picking up loose scraps of coal along the railways to sell or for use heating their homes. [1] Many coal miners disdained the C&Is and called them "Cossacks" and "Yellow Dogs". [5] Common gunmen, hoodlums, and adventurers were often hired to fill these commissions. They served their own interests and regularly abused their power.

The first Coal and Iron Police were established in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, under the supervision of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Beginning in 1873, the Coal and Iron Police worked with the Pinkertons, particularly with a labor spy by the name of James McParland, to infiltrate and suppress supposed Molly Maguire activity in the coal fields. During McParland's undercover investigation, Allan Pinkerton pursued a dual-track strategy, appointing R.J. Linden as head of the local Coal and Iron Police. McParland's undercover work led to the arrest and execution of 20 suspected Molly Maguires, but not without complications. Carbon County judge John P. Lavelle later wrote that:

The Molly Maguire trials were a surrender of state sovereignty. A private corporation initiated the investigation through a private detective agency. A private police force arrested the alleged defenders, and private attorneys for the coal companies prosecuted them. The state provided only the courtroom and the gallows. [6]

Violence continued throughout the investigation. Tamaqua police officer Benjamin Yost was murdered in 1875 and the Mollies were blamed. Later that year, an Irish family was murdered by gunmen under suspicious circumstances. The attack was thought to have been motivated by revenge for the alleged murder of mine boss Thomas Sanger by Charles Kehoe, a leader of the Mollies. Though the gunmen were never brought to trial, later evidence implicated Pinkerton, McParland, and Linden. Many in the Irish-American working class at the time, and some scholars today, question whether tales of the Molly Maguires were invented by the Pinkertons to justify repression in the anthracite coal fields. Many suspected Mollies maintained their innocence throughout the proceedings against them. [1] [7]

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 led to increased public-private police cooperation, with Pennsylvania National Guard regiments and eventually federal troops deployed when Pinkertons and Coal and Iron Police failed to quell disorder on their own. The difficulties faced by Pennsylvania authorities in routing entrenched strikers led to reforms in the state's National Guard, and established a stronger role for the state in preserving order in industrial disputes. [1]

On 16 March 1892 Coal and Iron police officer John Merget was shot and killed when he tried to stop 3 tramps from stealing from a boxcar; two suspects were convicted of second degree murder. [8]

Coal and Iron Police again played a significant role in the 1892 Homestead Strike. As in 1877, The C&Is were overwhelmed by striking workers. They were herded together with the sheriff and local militia and sent away from town on a boat. The state's National Guard was again summoned to put down the strike. [1]

In 1897, at least nineteen striking mineworkers were killed and dozens more were injured while marching to Lattimer, after a posse of deputies and company police fired on the unarmed crowd. The Lattimer Massacre bolstered sympathy and support for the miners' grievances and marked a turning point in the history of the United Mine Workers of America. None of the deputies or company police were convicted for the murder of the unarmed workers. [1]