Related Research Articles

Alcuin of York – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was an English scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student of Archbishop Ecgbert at York. At the invitation of Charlemagne, he became a leading scholar and teacher at the Carolingian court, where he remained a figure in the 780s and 790s. "The most learned man anywhere to be found", according to Einhard's Life of Charlemagne, he is considered among the most important intellectual architects of the Carolingian Renaissance. Among his pupils were many of the dominant intellectuals of the Carolingian era.

Alfonso II of Asturias, nicknamed the Chaste, was the king of Asturias during two different periods: first in the year 783 and later from 791 until his death in 842. Upon his death, Nepotian, a family member of undetermined relation, attempted to usurp the crown in place of the future Ramiro I.

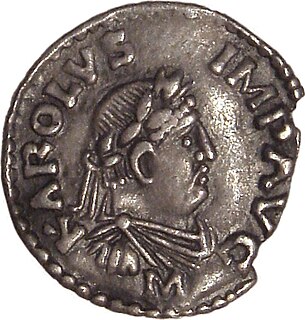

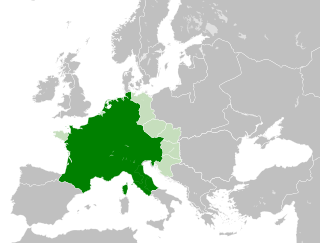

Charlemagne or Charles the Great, a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy Roman Emperor from 800. Charlemagne succeeded in uniting the majority of western and central Europe and was the first recognized emperor to rule from western Europe since the fall of the Western Roman Empire around three centuries earlier. The expanded Frankish state that Charlemagne founded was the Carolingian Empire. He was canonized by Antipope Paschal III— an act later treated as invalid—and he is now regarded by some as beatified in the Catholic Church.

Pope Adrian I was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 1 February 772 to his death. He was the son of Theodore, a Roman nobleman.

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans during the Middle Ages, and also known as the German-Roman Emperor since the early modern period, was the ruler and head of state of the Holy Roman Empire. The empire was considered by the Roman Catholic Church to be the only successor of the Roman Empire during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The title was held in conjunction with the title of king of Italy from the 8th to the 16th century, and, almost without interruption, with the title of king of Germany throughout the 12th to 18th centuries.

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lombards in Italy from 774. In 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III in an effort to transfer the Roman Empire from east to west. The Carolingian Empire is considered the first phase in the history of the Holy Roman Empire, which lasted until 1806.

Carloman I, also Karlmann, was king of the Franks from 768 until his death in 771. He was the second surviving son of Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon and was a younger brother of Charlemagne. His death allowed Charlemagne to take all of Francia and begin his expansion into other kingdoms.

Desiderius, also known as Daufer or Dauferius, was king of the Lombards in northern Italy, ruling from 756 to 774. The Frankish king of renown, Charlemagne, married Desiderius's daughter and subsequently conquered his realm. Desiderius is remembered for this connection to Charlemagne and for being the last Lombard ruler to exercise regional kingship.

Translatio imperii is a historiographical concept that originated from the Middle Ages, in which history is viewed as a linear succession of transfers of an imperium that invests supreme power in a singular ruler, an "emperor". The concept is closely linked to translatio studii. Both terms are thought to have their origins in the second chapter of the Book of Daniel in the Hebrew Bible.

Aistulf was the Duke of Friuli from 744, King of the Lombards from 749, and Duke of Spoleto from 751. His reign was characterized by ruthless and ambitious efforts to conquer Roman territory to the extent that in the Liber Pontificalis, he is described as a "shameless" Lombard given to "pernicious savagery" and cruelty.

Lorsch Abbey, otherwise the Imperial Abbey of Lorsch, is a former Imperial abbey in Lorsch, Germany, about 10 km (6.2 mi) east of Worms. It was one of the most renowned monasteries of the Carolingian Empire. Even in its ruined state, its remains are among the most important pre-Romanesque–Carolingian style buildings in Germany. Its chronicle, entered in the Lorscher Codex compiled in the 1170s, is a fundamental document for early medieval German history. Another famous document from the monastic library is the Codex Aureus of Lorsch. In 1991 the ruined abbey was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Pepin the Short, also called the Younger was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The Council of Frankfurt, traditionally also the Council of Frankfort, in 794 was called by Charlemagne, as a meeting of the important churchmen of the Frankish realm. Bishops and priests from Francia, Aquitaine, Italy, and Provence gathered in Franconofurd. The synod, held in June 794, allowed the discussion and resolution of many central religious and political questions.

Saint Fulrad was born in 710 into a wealthy family, and died on July 16, 784 as the Abbot of Saint-Denis He was the counselor of both Pippin and Charlemagne. Historians see Fulrad as important due to his significance in the rise of the Frankish Kingdom, and the insight he gives into early Carolingian society. He was noted to have been always on the side on Charlemagne, especially during the attack from the Saxons on Regnum Francorum, and the Royal Mandatum. Other historians have taken a closer look at Fulrad's interactions with the papacy. When Fulrad was the counselor of Pepin he was closely in contact with the papacy to gain approval for Pepin's appointment as King of the Franks. During his time under Charlemagne, he had dealings with the papacy again for different reasons. When he became Abbot of Saint-Denis in the mid-eighth century, Fulrad's life became important in the lives of distinct historical figures in various ways. Saint Fulrad's Feast Day is on July 16.

The Annales laureshamenses, also called Annals of Lorsch (AL), are a set of Reichsannalen that cover the years from 703 to 803, with a brief prologue. The annals begin where the "Chronica minora" of the Anglo-Saxon historian Bede leaves off—in the fifth year of the Emperor Tiberios III—and may have originally been composed as a continuation of Bede. The annals for the years up to 785 were written at the Abbey of Lorsch, but are dependent on earlier sources. Those for the years from 785 onward form an independent source and provide especially important coverage of the imperial coronation of Charlemagne in 800. The Annales laureshamenses have been translated into English.

Spanish Adoptionism was a Christian theological position which was articulated in Umayyad and Christian-held regions of the Iberian peninsula in the 8th- and 9th centuries. The issue seems to have begun with the claim of archbishop Elipandus of Toledo that – in respect to his human nature – Jesus Christ was adoptive Son of God. Another leading advocate of this Christology was Felix of Urgel. In Spain, Adoptionism was opposed by Beatus of Liebana, and in the Carolingian territories, the Adoptionist position was condemned by Pope Hadrian I, Alcuin of York, Agobard, and officially in Carolingian territory by the Council of Frankfurt (794).

The Collectiones canonum Dionysianae, also known as Collectio Dionysiana or Dionysiana Collectio, are the several collections of ancient canons prepared by a Scythian monk, Dionysius 'the humble' (exiguus). They include the Collectio conciliorum Dionysiana I, the Collectio conciliorum Dionysiana II, and the Collectio decretalium Dionysiana. They are of the utmost importance for the development of the canon law tradition in the West.

Leo I was archbishop of Ravenna from A.D. 770, following a disputed election, until his death in A.D. 777. Archbishop Leo played an important role in the arrest of Paul Afiarta and was the subject of letters from Pope Hadrian I to Charlemagne collected in the Codex Carolinus and dated from late 774.

Wilchar was the archbishop of the province of the Gauls, succeeding Chrodegang after 766 as the leading bishop in the kingdom of the Franks. Before receiving the pallium, he ruled a suburbicarian diocese in Rome. As archbishop, he held the diocese of Sens for a time (762/769–772/778) and afterwards held authority over all Gaul without a fixed see.

The Migetians or Cassianists were a rigorist Christian sect in Muslim Spain in the late 8th and early 9th centuries. Their writings are lost and they are known primarily through the letters of their opponents, Archbishop Elipand of Toledo and Pope Hadrian I. The founder of the sect, Migetius, was condemned as a heretic by the Spanish church before 785 and again in 839. He managed to convert a bishop sent from Francia, which briefly brought the sect to the attention of foreign powers. A larger consequence of this was to bring to Frankish and papal awareness the prevalence of Adoptionism in the Spanish church.

References

- ↑ "Codex Epistolaris Carolinus". Liverpool University Press. 2021. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ↑ van Espelo, Dorine (August 2013). "A testimony of Carolingian rule? The Codex epistolaris carolinus, its historical context, and the meaning of imperium in Early Medieval Europe". Early Medieval Europe. 21 (3): 254–282 (p.260). doi:10.1111/emed.12018. S2CID 247659439.

- ↑ McKitterick, Rosamund; Espelo, Dorine van; Pollard, Richard; Price, Richard (2021). Codex Epistolaris Carolinus Letters from the popes to the Frankish rulers, 739-791. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- 1 2 Ibid., p.255

- ↑ Ibid., p.268.

- ↑ Ibid., p.265.

- ↑ Ibid., p.255.

- ↑ Ibid., p.281.

- ↑ Noble, Thomas (1986). The Republic of St. Peter : The Birth of the Papal State, 680-825. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 280.

- ↑ Espelo, Early Medieval Europe, p.280.

- ↑ Ibid., p.257-8.