Charlemagne was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and Emperor of the Carolingian Empire from 800, holding all these titles until his death in 814. Charlemagne succeeded in uniting the majority of Western Central Europe, and was the first recognized emperor to rule in the west after the fall of the Western Roman Empire approximately three centuries earlier. Charlemagne's rule saw a program of political and social changes that had a lasting impact on Europe in the Middle Ages.

Louis the Pious, also called the Fair and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aquitaine from 781. As the only surviving son of Charlemagne and Hildegard, he became the sole ruler of the Franks after his father's death in 814, a position that he held until his death except from November 833 to March 834, when he was deposed.

Pope Adrian I was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 1 February 772 to his death. He was the son of Theodore, a Roman nobleman.

The Second Council of Nicaea is recognized as the last of the first seven ecumenical councils by the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church. In addition, it is also recognized as such by the Old Catholics, and others. Protestant opinions on it are varied.

Year 794 (DCCXCIV) was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar, the 794th year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 794th year of the 1st millennium, the 94th year of the 8th century, and the 5th year of the 790s decade. The denomination 794 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

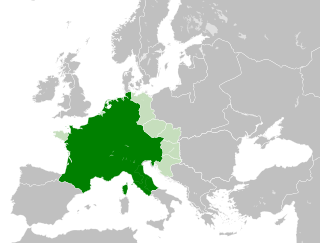

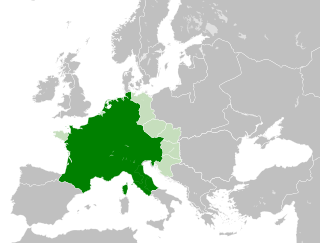

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lombards in Italy from 774. In 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III in an effort to transfer the Roman Empire from the Byzantine Empire to Western Europe. The Carolingian Empire is sometimes considered the first phase in the history of the Holy Roman Empire.

A missus dominicus, Latin for "envoy[s] of the lord [ruler]" or palace inspector, also known in Dutch as Zendgraaf, meaning "sent Graf", was an official commissioned by the Frankish king or Holy Roman Emperor to supervise the administration, mainly of justice, in parts of his dominions too remote for frequent personal visits. As such, the missus performed important intermediary functions between royal and local administrations. There are superficial points of comparison with the original Roman corrector, except that the missus was sent out on a regular basis. Four points made the missi effective as instruments of the centralized monarchy: the personal character of the missus, yearly change, isolation from local interests and the free choice of the king.

The Kingdom of the Franks, also known as the Frankish Kingdom, the Frankish Empire or Francia, was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Frankish Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties during the Early Middle Ages. Francia was among the last surviving Germanic kingdoms from the Migration Period era.

Fastrada was queen consort of East Francia by marriage to Charlemagne, as his third wife.

Iconodulism designates the religious service to icons. The term comes from Neoclassical Greek εἰκονόδουλος (eikonodoulos), meaning "one who serves images (icons)". It is also referred to as iconophilism designating a positive attitude towards the religious use of icons. In the history of Christianity, iconodulism was manifested as a moderate position, between two extremes: iconoclasm and iconolatry.

Tassilo III was the duke of Bavaria from 748 to 788, the last of the house of the Agilolfings. He was the son of Duke Odilo of Bavaria and Hitrud, daughter of Charles Martel.

A capitulary was a series of legislative or administrative acts emanating from the Frankish court of the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties, especially that of Charlemagne, the first emperor of the Romans in the west since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century. They were so called because they were formally divided into sections called capitula.

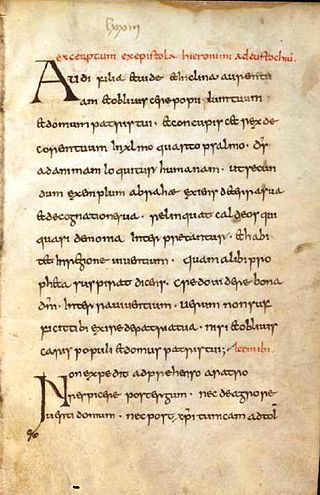

Theodulf of Orléans was a writer, poet and the Bishop of Orléans during the reign of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious. He was a key member of the Carolingian Renaissance and an important figure during the many reforms of the church under Charlemagne, as well as almost certainly the author of the Libri Carolini, "much the fullest statement of the Western attitude to representational art that has been left to us by the Middle Ages". He is mainly remembered for this and the survival of the private oratory or chapel made for his villa at Germigny-des-Prés, with a mosaic probably from about 806. In Bible manuscripts produced under his influence, the Book of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah became part of the Western (Vulgate) Bible canon.

The Libri Carolini, more correctly Opus Caroli regis contra synodum, is a work in four books composed on the command of Charlemagne in the mid 790s to refute the conclusions of the Byzantine Second Council of Nicaea (787), particularly as regards the matter of sacred images. They are "much the fullest statement of the Western attitude to representational art that has been left to us by the Middle Ages".

Liutperga (Liutpirc) (fl 750 - fl. 793) was a Duchess of Bavaria by marriage to Tassilo III, the last Agilolfing Duke of Bavaria. She was the daughter of Desiderius, King of the Lombards, and Ansa.

The Admonitio generalis is a collection of legislation known as a capitulary issued by Charlemagne in 789, which covers educational and ecclesiastical reform within the Frankish kingdom. Capitularies were used in the Frankish kingdom during the Carolingian dynasty by government and administration bodies and covered a variety of topics, sorted into chapters. Admonitio generalis is actually just one of many Charlemagne's capitularies that outlined his desire for a well-governed, disciplined Christian Frankish kingdom. The reforms issued in these capitularies by Charlemagne during the late 8th century reflect the cultural revival known as the Carolingian Renaissance.

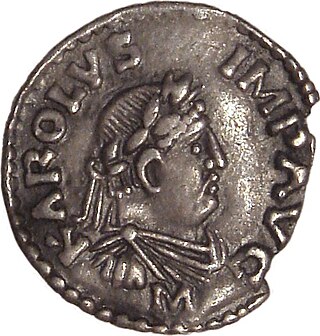

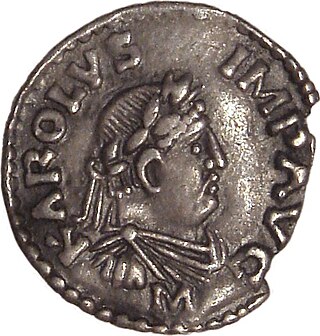

The Aachen penny of Charlemagne, a Carolingian silver coin, was found on 22 February 2008 in the foundations of the Palatine Chapel in Aachen, during archaeological work in the northeastern bay of the hexadecagon. This is the first discovery of coinage from the time of Charlemagne at Aachen.

The Synods of Aachen between 816 and 819 were a landmark in regulations for the monastic life in the Frankish realm. The Benedictine Rule was declared the universally valid norm for communities of monks and nuns, while canonical orders were distinguished from monastic communities and unique regulations were laid down for them: the Institutio canonicorum Aquisgranensis. The synods of 817 and 818/819 completed the reforms. Among other things, the relationship of church properties to the king was clarified.

The Codex epistolaris Carolinus is a collection of 99 letters from reigning popes to Carolingian rulers written between 739 and 791.

The Carolingian Church encompasses the practices and institutions of Christianity in the Frankish kingdoms under the rule of the Carolingian dynasty (751-888). In the eighth and ninth centuries, Western Europe witnessed decisive developments in the structure and organisation of the church, relations between secular and religious authorities, monastic life, theology, and artistic endeavours. Christianity was the principal religion of the Carolingian Empire. Through military conquests and missionary activity, Latin Christendom expanded into new areas, such as Saxony and Bohemia. These developments owed much to the leadership of Carolingian rulers themselves, especially Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, whose courts encouraged successive waves of religious reform and viewed Christianity as a unifying force in their empire.