The Romaniote Jews or the Romaniotes are a Greek-speaking ethnic Jewish community native to the Eastern Mediterranean. They are one of the oldest Jewish communities in existence and the oldest Jewish community in Europe. The Romaniotes have been, and remain, historically distinct from the Sephardim, some of whom settled in Ottoman Greece after the expulsion of Jews from Spain and Portugal after 1492.

Karaite Judaism or Karaism is a Jewish religious movement characterized by the recognition of the written Tanakh alone as its supreme authority in halakha and theology. Karaites believe that all of the divine commandments which were handed down to Moses by God were recorded in the written Torah without any additional Oral Law or explanation. Unlike mainstream Rabbinic Judaism, which regards the Oral Torah, codified in the Talmud and subsequent works, as authoritative interpretations of the Torah, Karaite Jews do not treat the written collections of the oral tradition in the Midrash or the Talmud as binding.

Yevanic, also known as Judaeo-Greek, Romaniyot, Romaniote, and Yevanitika, is a Greek dialect formerly used by the Romaniotes and by the Constantinopolitan Karaites. The Romaniotes are a group of Greek Jews whose presence in the Levant is documented since the Byzantine period. Its linguistic lineage stems from the Jewish Koine spoken primarily by Hellenistic Jews throughout the region, and includes Hebrew and Aramaic elements. It was mutually intelligible with the Greek dialects of the Christian population. The Romaniotes used the Hebrew alphabet to write Greek and Yevanic texts. Judaeo-Greek has had in its history different spoken variants depending on different eras, geographical and sociocultural backgrounds. The oldest Modern Greek text was found in the Cairo Geniza and is actually a Jewish translation of the Book of Ecclesiastes (Kohelet).

Yefet ben Ali was perhaps the foremost Karaite commentator on the Bible, during the "Golden Age of Karaism". He lived about 95 years, c. 914-1009. Born in Basra in the Abbasid Caliphate, he later moved to Jerusalem between 950 and 980, where he died. The Karaites distinguished him by the epithet maskil ha-Golah.

Schisms among the Jews are cultural as well as religious. They have happened as a product of historical accident, geography, and theology.

The Krymchaks are Jewish ethno-religious communities of Crimea derived from Turkic-speaking adherents of Rabbinic Judaism. They have historically lived in close proximity to the Crimean Karaites, who follow Karaite Judaism.

Benjamin Nahawandi or Benjamin ben Moses Nahawendi was a prominent Persian Jewish scholar of Karaite Judaism. He was claimed to be one of the greatest of the Karaite scholars of the early Middle Ages. The Karaite historian Solomon ben Jeroham regarded him as greater even than Anan ben David. His name indicates that he is originally from Nahawand, a town in Iran (Persia).

Abraham (Avraham) ben Samuel Firkovich was a famous Karaite writer and archaeologist, collector of ancient manuscripts, and a Karaite Hakham. He was born in Lutsk, Volhynia, then lived in Lithuania, and finally settled in Çufut Qale, Crimea, where he also died. Gabriel Firkovich of Troki was his son-in-law.

Aaron ben Elijah, the Latter, of Nicomedia is often considered to be the most prominent Karaite theologian. He is referred to as "the Younger" to distinguish him from Aaron the Elder. Even though Aaron lived for much of his life in Constantinople, he is sometimes distinguished from another Aaron Ben Elijah by the title "of Nicomedia," signifying another place he lived.

Elijah Mizrachi was a Talmudist and posek, an authority on Halakha, and a mathematician. He is best known for his Sefer ha-Mizrachi, a supercommentary on Rashi's commentary on the Torah. He is also known as Re'em, the Hebrew acronym for "Rabbi Elijah Mizrachi", coinciding with the Biblical name of an animal, the re'em, which sometimes translated as "unicorn".

Aaron ben Joseph of Constantinople, was an eminent teacher, philosopher, physician, and liturgical poet in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire.

Elijah ben Moses Bashyazi of Adrianople or Elijah Bašyazi was a Karaite Jewish hakham of the fifteenth century. After being instructed in the Karaite literature and theology of his father and grandfather, both learned hakhams of the Karaite community of Adrianople, Bashyazi went to Constantinople, where, under the direction of Mordecai Comtino, he studied rabbinical literature as well as mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy, in all of which he soon became most proficient.

Judah ben Tabbai was a Pharisee scholar, av beit din of the Sanhedrin, and one of "the Pairs" (zugot) of Jewish leaders who lived in the first century BCE.

Jews were numerous and had significant roles throughout the history of the Byzantine Empire.

Simḥah Isaac ben Moses Luzki, also known as the "Karaite Rashi" and "Olam Tsa'ir," was a Karaite Kabbalist, writer, and bibliographer.

Daniel Judah Lasker is an American-born Israeli scholar of Jewish philosophy. As of 2017, he is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Jewish thought at Ben Gurion University of the Negev.

Moses ben Elijah Bashyazi (1537–1555) was a Karaite scholar and great-grandson of Elijah Bashyazi. He was born in Constantinople and at 16 years of age, he displayed a remarkable degree of learning and a profound knowledge of foreign languages. He undertook for mere love of knowledge a voyage to the Land of Israel and Syria in order to explore these countries and to collect old manuscripts. Though he died at such an early age, he had composed many works, four of which are extant in manuscript:

- "Sefer Yehudah" or "Sefer 'Arayot," on prohibited marriages. In this work he enumerates former authors who had written on the same subject, such as Joseph ben Abraham, Jeshua ben Judah, and Aaron ben Elijah.

- "Zebach Pesach", on the celebration of the festival days, in which he quotes many passages from the Arabic originals of Jeshuah ben Judah's commentary upon the Torah, from the commentary of Jacob Qirqisani, from Jeshuah ben Judah's other works, and from the "Sefer ha-Mizvot" of Daniel al-Kumisi.

- "Matteh Elohim", which contains a history of the Karaite-Rabbinic schism; the chain of Karaite tradition, which the author claims to have received from Japheth ibn Saghir; interpretation of the Torah, and particularly of the precepts which are arranged in numbers according to the Ten Commandments.

- "Sefer Reuben", on dogmas and articles of belief.

Istanbul became one of the world's most important Jewish centers in the 16th and 17th centuries. In marked contrast to Jews in Europe, Ottoman Jews were allowed to work in any profession and could also enter the Ottoman court. Ottoman Jews in Istanbul excelled in commerce and trade and came to dominate the medical profession. Despite making up only 10% of the city population, Jews constituted 62% of licensed doctors in 1600.

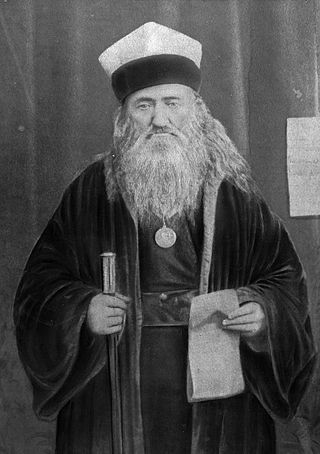

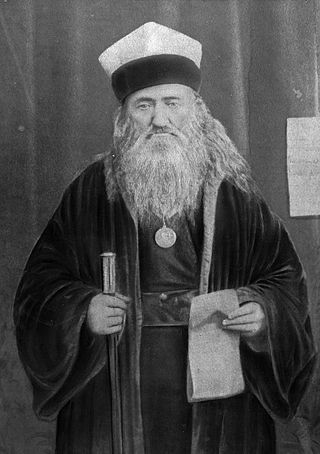

Shlomo ben Afeda Ha-Kohen or Solomon Afeda Cohen (1826–1893) was a Karaite Jewish hakham of the 19th century considered the last of the Karaite sages of Constantinople.