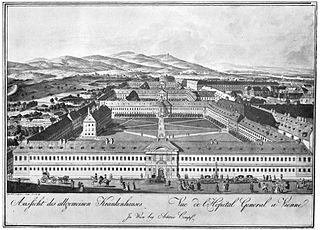

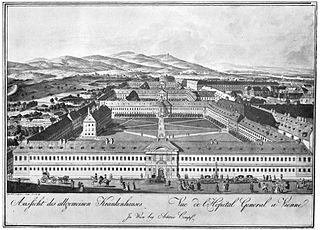

Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis was a Hungarian physician and scientist of German descent who was an early pioneer of antiseptic procedures and was described as the "saviour of mothers". Postpartum infection, also known as puerperal fever or childbed fever, consists of any bacterial infection of the reproductive tract following birth and in the 19th century was common and often fatal. Semmelweis discovered that the incidence of infection could be drastically reduced by requiring healthcare workers in obstetrical clinics to disinfect their hands. In 1847, he proposed hand washing with chlorinated lime solutions at Vienna General Hospital's First Obstetrical Clinic, where doctors' wards had three times the mortality of midwives' wards. The maternal mortality rate dropped from 18% to less than 2%, and he published a book of his findings, Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever, in 1861.

Postpartum infections, also known as childbed fever and puerperal fever, are any bacterial infections of the female reproductive tract following childbirth or miscarriage. Signs and symptoms usually include a fever greater than 38.0 °C (100.4 °F), chills, lower abdominal pain, and possibly bad-smelling vaginal discharge. It usually occurs after the first 24 hours and within the first ten days following delivery.

Ferdinand Karl Franz Schwarzmann, Ritter von Hebra was an Austrian Empire physician and dermatologist known as the founder of the New Vienna School of Dermatology, an important group of physicians who established the foundations of modern dermatology.

Pyaemia is a type of sepsis that leads to widespread abscesses of a metastatic nature. It is usually caused by the staphylococcus bacteria by pus-forming organisms in the blood. Apart from the distinctive abscesses, pyaemia exhibits the same symptoms as other forms of septicaemia. It was almost universally fatal before the introduction of antibiotics.

Johann Baptist Chiari was an Austrian gynecologist and obstetrician born in Salzburg.

The Cry and the Covenant is a novel by Morton Thompson written in 1949 and published by Doubleday. The novel is a fictionalized story of Ignaz Semmelweis, an Austrian-Hungarian physician known for his research into puerperal fever and his advances in medical hygiene. The novel includes historical references, and details into Semmelweis' youth and education, as well as his later studies.

Historically, puerperal fever was a devastating disease. It affected women within the first three days after childbirth and progressed rapidly, causing acute symptoms of severe abdominal pain, fever and debility.

Franz Kiwisch von Rotterau was Professor of Obstetrics at the University of Würzburg and later at the University of Prague. He was one of Semmelweis's principal opponents. In Würzburg he was succeeded by Friedrich Wilhelm Scanzoni von Lichtenfels.

Jakob Kolletschka was Professor of Forensic Medicine at Vienna General Hospital in Austria.

Carl Edvard Marius Levy was professor and head of the Danish Maternity institution in Copenhagen. His name is sometimes spelled "Carl Eduard Marius Levy" or, in foreign literature, "Karl Edouard Marius Levy".

Johann Klein was professor of obstetrics at the University of Salzburg and at the University of Vienna. Johann Baptist Chiari was his son-in-law. In Vienna, he was succeeded by professor Carl Braun in 1856.

Carl Braun, sometimes Carl Rudolf Braun alternative spelling: Karl Braun, or Karl von Braun-Fernwald, name after knighthood Carl Ritter von Fernwald Braun was an Austrian obstetrician. He was born 22 March 1822 in Zistersdorf, Austria, son of the medical doctor Carl August Braun.

Johann Lucas Boër, originally Johann Lucas Boogers was a German medical doctor and obstetrician.

Joseph Späth was professor of obstetrics in Vienna, and from 1873 to 1886 he was director of the second obstetrical clinic at the Vienna General Hospital.

The Semmelweis reflex or "Semmelweis effect" is a metaphor for the reflex-like tendency to reject new evidence or new knowledge because it contradicts established norms, beliefs, or paradigms.

Eduard Lumpe (1813–1876) was an obstetrician working in Vienna General Hospital as assistant to professor Johann Klein. He is mainly known for compiling a list of causes for childbed fever in 1845, reflecting the insights at the time. The disease was predominantly epidemic, i.e. due to miasmatic influences. Other causal factors included: general deprivation, worry, shame, attempted abortion, fear of death, dietary disorders, exposure to cold, local miasmas and difficult delivery. Ignaz Semmelweis ridiculed Lumpe's work.

Joseph Hermann Schmidt was professor of obstetrics in Berlin, and official of the Prussian cultural ministry.

Carl Mayrhofer was a physician conducting work on the role of germs in childbed fever.

Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever is a pioneering medical book written by Ignaz Semmelweis and published in 1861, which explains how hygiene in hospitals can drastically reduce unnecessary deaths. The book and concept saved millions of mothers from a preventable streptococcal infection.

Antoine Germain Labarraque was a French chemist and pharmacist, notable for formulating and finding important uses for "Eau de Labarraque" or "Labarraque's solution", a solution of sodium hypochlorite widely used as a disinfectant and deodoriser.