Joanna, historically known as Joanna the Mad, was the nominal queen of Castile from 1504 and queen of Aragon from 1516 to her death in 1555. She was the daughter of Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. Joanna was married by arrangement to the Austrian archduke Philip the Handsome on 20 October 1496. Following the deaths of her elder brother John, elder sister Isabella, and nephew Miguel between 1497 and 1500, Joanna became the heir presumptive to the crowns of Castile and Aragon. When her mother died in 1504, she became queen of Castile. Her father proclaimed himself governor and administrator of Castile.

John II, called the Great or the Faithless, was King of Aragon from 1458 until his death in 1479. As the husband of Queen Blanche I of Navarre, he was King of Navarre from 1425 to 1479. John was also King of Sicily from 1458 to 1468.

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the de facto unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being both descended from John I of Castile; to remove the obstacle that this consanguinity would otherwise have posed to their marriage under canon law, they were given a papal dispensation by Sixtus IV. They married on October 19, 1469, in the city of Valladolid; Isabella was 18 years old and Ferdinand a year younger. Most scholars generally accept that the unification of Spain can essentially be traced back to the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella. Their reign was called by W.H. Prescott "the most glorious epoch in the annals of Spain".

The count of Barcelona was the ruler of the County of Barcelona and also, by extension and according with the Usages and Catalan constitutions, of the Principality of Catalonia as Princeps for much of Catalan history, from the 9th century until the 18th century. After 1164, with Alfonso II of Aragon and I of Barcelona, the title of count of Barcelona was united with that of king of Aragon, and after the 16th century, with that of king of Spain.

The Kingdom of Aragon was a medieval and early modern kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, corresponding to the modern-day autonomous community of Aragon, in Spain. It should not be confused with the larger Crown of Aragon, which also included other territories—the Principality of Catalonia, the Kingdom of Valencia, the Kingdom of Majorca, and other possessions that are now part of France, Italy, and Greece—that were also under the rule of the King of Aragon, but were administered separately from the Kingdom of Aragon.

The Crown of Aragon was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of Barcelona and ended as a consequence of the War of the Spanish Succession. At the height of its power in the 14th and 15th centuries, the Crown of Aragon was a thalassocracy controlling a large portion of present-day eastern Spain, parts of what is now southern France, and a Mediterranean empire which included the Balearic Islands, Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia, Malta, Southern Italy, and parts of Greece.

Spain in the Middle Ages is a period in the history of Spain that began in the 5th century following the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ended with the beginning of the early modern period in 1492.

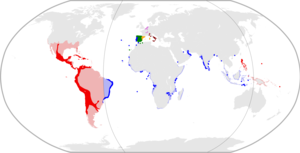

The Iberian Union is a historiographical term used to describe the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Portugal with the Monarchy of Spain, which in turn was itself the personal union of the crowns of Castile and Aragon, and of their respective colonial empires, that existed between 1580 and 1640 and brought the entire Iberian Peninsula except Andorra, as well as Portuguese and Spanish overseas possessions, under the Spanish Habsburg monarchs Philip II, Philip III, and Philip IV. The union began after the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580 and the ensuing War of the Portuguese Succession, and lasted until the Portuguese Restoration War, during which the House of Braganza was established as Portugal's new ruling dynasty with the acclamation of John IV as the new king of Portugal.

The Kingdom of Valencia, located in the eastern shore of the Iberian Peninsula, was one of the component realms of the Crown of Aragon.

The Principality of Catalonia was a medieval and early modern state in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula. During most of its history it was in dynastic union with the Kingdom of Aragon, constituting together the Crown of Aragon. Between the 13th and the 18th centuries, it was bordered by the Kingdom of Aragon to the west, the Kingdom of Valencia to the south, the Kingdom of France and the feudal lordship of Andorra to the north and by the Mediterranean Sea to the east. The term Principality of Catalonia was official until the 1830s, when the Spanish government implemented the centralized provincial division, but remained in popular and informal contexts. Today, the term Principat (Principality) is used primarily to refer to the autonomous community of Catalonia in Spain, as distinct from the other Catalan Countries, and usually including the historical region of Roussillon in Southern France.

The Council of the Indies, officially the Royal and Supreme Council of the Indies, was the most important administrative organ of the Spanish Empire for the Americas and those territories it governed, such as the Spanish East Indies. The crown held absolute power over the Indies and the Council of the Indies was the administrative and advisory body for those overseas realms. It was established in 1524 by Charles V to administer "the Indies", Spain's name for its territories. Such an administrative entity, on the conciliar model of the Council of Castile, was created following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire in 1521, which demonstrated the importance of the Americas. Originally an itinerary council that followed Charles V, it was subsequently established as an autonomous body with legislative, executive and judicial functions by Philip II of Spain and placed in Madrid in 1561.

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accession of the then Castilian king, Ferdinand III, to the vacant Leonese throne. It continued to exist as a separate entity after the personal union in 1469 of the crowns of Castile and Aragon with the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs up to the promulgation of the Nueva Planta decrees by Philip V in 1716.

The Council of Castile, known earlier as the Royal Council, was a ruling body and key part of the domestic government of the Crown of Castile, second only to the monarch himself.

Ferdinand II was King of Aragon from 1479 until his death in 1516. As the husband of and co-ruler with Queen Isabella I of Castile, he was also King of Castile from 1475 to 1504. He reigned jointly with Isabella over a dynastically unified Spain; together they are known as the Catholic Monarchs. Ferdinand is considered the de facto first king of Spain, and was described as such during his reign, even though, legally, Castile and Aragon remained two separate kingdoms until they were formally united by the Nueva Planta decrees issued between 1707 and 1716.

Pedro Folc de Cardona, an illegitimate son of Joan Ramon Folc de Cardona y de Prades, 3rd Count of Cardona, was bishop of Urgell (1472–1515), president of the Generalitat of Catalonia (1482–85), editor of the Usatges de Barcelona (1505), viceroy of Catalonia (1521–23) and archbishop of Tarragona (1515–30).

The Council of Italy, officially the Royal and Supreme Council of Italy, was a ruling body and key part of the government of the Spanish Empire in Europe, second only to the monarch himself. It was based in Madrid and administered the Spanish territories in Italy: the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Sicily, the Duchy of Milan, State of the Presidi, Marquisate of Finale and other minor territories.

The Polysynodial System, Polysynodial Regime or System of Councils was the way of organization of the composite monarchy ruled by the Catholic Monarchs and the Spanish Habsburgs, which entrusted the central administration in a group of collegiate bodies (councils) already existing or created ex novo. Most of the councils were formed by lawyers trained in academic study of Roman law. After its creation in 1521, the Council of State, chaired by the monarch and formed by the high nobility and clergy, became the supreme body of the monarchy. The polysynodial system met its demise in the early 18th century in the wake of the promulgation of the Nueva Planta decrees by the incoming Bourbon dynasty, which organized a system underpinned by Secretaries of State.