In finance, default is failure to meet the legal obligations of a loan, for example when a home buyer fails to make a mortgage payment, or when a corporation or government fails to pay a bond which has reached maturity. A national or sovereign default is the failure or refusal of a government to repay its national debt.

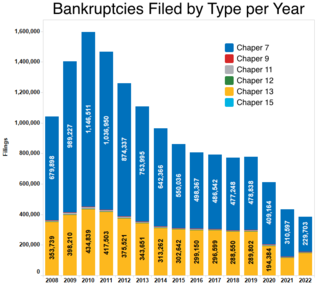

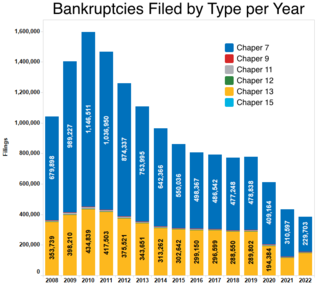

Chapter 7 of Title 11 of the United States Code governs the process of liquidation under the bankruptcy laws of the United States, in contrast to Chapters 11 and 13, which govern the process of reorganization of a debtor. Chapter 7 is the most common form of bankruptcy in the United States.

Debt is an obligation that requires one party, the debtor, to pay money or other agreed-upon value to another party, the creditor. Debt is a deferred payment, or series of payments, which differentiates it from an immediate purchase. The debt may be owed by sovereign state or country, local government, company, or an individual. Commercial debt is generally subject to contractual terms regarding the amount and timing of repayments of principal and interest. Loans, bonds, notes, and mortgages are all types of debt. In financial accounting, debt is a type of financial transaction, as distinct from equity.

Debt consolidation is a form of debt refinancing that entails taking out one loan to pay off many others. This commonly refers to a personal finance process of individuals addressing high consumer debt, but occasionally it can also refer to a country's fiscal approach to consolidate corporate debt or government debt. The process can secure a lower overall interest rate to the entire debt load and provide the convenience of servicing only one loan or debt.

Title 11 of the United States Code sets forth the statutes governing the various types of relief for bankruptcy in the United States. Chapter 13 of the United States Bankruptcy Code provides an individual with the opportunity to propose a plan of reorganization to reorganize their financial affairs while under the bankruptcy court's protection. The purpose of chapter 13 is to enable an individual with a regular source of income to propose a chapter 13 plan that provides for their various classes of creditors. Under chapter 13, the Bankruptcy Court has the power to approve a chapter 13 plan without the approval of creditors as long as it meets the statutory requirements under chapter 13. Chapter 13 plans are usually three to five years in length and may not exceed five years. Chapter 13 is in contrast to the purpose of Chapter 7, which does not provide for a plan of reorganization, but provides for the discharge of certain debt and the liquidation of non-exempt property. A Chapter 13 plan may be looked at as a form of debt consolidation, but a Chapter 13 allows a person to achieve much more than simply consolidating his or her unsecured debt such as credit cards and personal loans. A chapter 13 plan may provide for the four general categories of debt: priority claims, secured claims, priority unsecured claims, and general unsecured claims. Chapter 13 plans are often used to cure arrearages on a mortgage, avoid "underwater" junior mortgages or other liens, pay back taxes over time, or partially repay general unsecured debt. In recent years, some bankruptcy courts have allowed Chapter 13 to be used as a platform to expedite a mortgage modification application.

Debt restructuring is a process that allows a private or public company or a sovereign entity facing cash flow problems and financial distress to reduce and renegotiate its delinquent debts to improve or restore liquidity so that it can continue its operations.

Foreclosure is a legal process in which a lender attempts to recover the balance of a loan from a borrower who has stopped making payments to the lender by forcing the sale of the asset used as the collateral for the loan.

A creditor or lender is a party that has a claim on the services of a second party. It is a person or institution to whom money is owed. The first party, in general, has provided some property or service to the second party under the assumption that the second party will return an equivalent property and service. The second party is frequently called a debtor or borrower. The first party is called the creditor, which is the lender of property, service, or money.

Refinancing is the replacement of an existing debt obligation with another debt obligation under a different term and interest rate. The terms and conditions of refinancing may vary widely by country, province, or state, based on several economic factors such as inherent risk, projected risk, political stability of a nation, currency stability, banking regulations, borrower's credit worthiness, and credit rating of a nation. In many industrialized nations, common forms of refinancing include primary residence mortgages and car loans.

In the United States, bankruptcy is largely governed by federal law, commonly referred to as the "Bankruptcy Code" ("Code"). The United States Constitution authorizes Congress to enact "uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States". Congress has exercised this authority several times since 1801, including through adoption of the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978, as amended, codified in Title 11 of the United States Code and the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (BAPCPA).

In finance, unsecured debt refers to any type of debt or general obligation that is not protected by a guarantor, or collateralized by a lien on specific assets of the borrower in the case of a bankruptcy or liquidation or failure to meet the terms for repayment. Unsecured debts are sometimes called signature debt or personal loans. These differ from secured debt such as a mortgage, which is backed by a piece of real estate.

Second mortgages, commonly referred to as junior liens, are loans secured by a property in addition to the primary mortgage. Depending on the time at which the second mortgage is originated, the loan can be structured as either a standalone second mortgage or piggyback second mortgage. Whilst a standalone second mortgage is opened subsequent to the primary loan, those with a piggyback loan structure are originated simultaneously with the primary mortgage. With regard to the method in which funds are withdrawn, second mortgages can be arranged as home equity loans or home equity lines of credit. Home equity loans are granted for the full amount at the time of loan origination in contrast to home equity lines of credit which permit the homeowner access to a predetermined amount which is repaid during the repayment period.

In finance, a security interest is a legal right granted by a debtor to a creditor over the debtor's property which enables the creditor to have recourse to the property if the debtor defaults in making payment or otherwise performing the secured obligations. One of the most common examples of a security interest is a mortgage: a person borrows money from the bank to buy a house, and they grant a mortgage over the house so that if they default in repaying the loan, the bank can sell the house and apply the proceeds to the outstanding loan.

A secured loan is a loan in which the borrower pledges some asset as collateral for the loan, which then becomes a secured debt owed to the creditor who gives the loan. The debt is thus secured against the collateral, and if the borrower defaults, the creditor takes possession of the asset used as collateral and may sell it to regain some or all of the amount originally loaned to the borrower. An example is the foreclosure of a home. From the creditor's perspective, that is a category of debt in which a lender has been granted a portion of the bundle of rights to specified property. If the sale of the collateral does not raise enough money to pay off the debt, the creditor can often obtain a deficiency judgment against the borrower for the remaining amount.

Bankruptcy is a legally declared inability or impairment of ability of an individual or organization to pay their creditors. In most cases personal bankruptcy is initiated by the bankrupt individual. Bankruptcy is a legal process that discharges most debts, but has the disadvantage of making it more difficult for an individual to borrow in the future. To avoid the negative impacts of personal bankruptcy, individuals in debt have a number of bankruptcy alternatives.

In finance, a secured transaction is a loan or a credit transaction in which the lender acquires a security interest in collateral owned by the borrower and is entitled to foreclose on or repossess the collateral in the event of the borrower's default. The terms of the relationship are governed by a contract, or security agreement. A common example would be a consumer who purchases a car on credit. If the consumer fails to make the payments on time, the lender will take the car and resell it, applying the proceeds of the sale toward the loan. Mortgages and deeds of trust are another example. In the United States, secured transactions in personal property are governed by Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code (U.C.C.).

In the United States, a mortgage note is a promissory note secured by a specified mortgage loan.

A mortgage loan or simply mortgage, in civil law jurisdicions known also as a hypothec loan, is a loan used either by purchasers of real property to raise funds to buy real estate, or by existing property owners to raise funds for any purpose while putting a lien on the property being mortgaged. The loan is "secured" on the borrower's property through a process known as mortgage origination. This means that a legal mechanism is put into place which allows the lender to take possession and sell the secured property to pay off the loan in the event the borrower defaults on the loan or otherwise fails to abide by its terms. The word mortgage is derived from a Law French term used in Britain in the Middle Ages meaning "death pledge" and refers to the pledge ending (dying) when either the obligation is fulfilled or the property is taken through foreclosure. A mortgage can also be described as "a borrower giving consideration in the form of a collateral for a benefit (loan)".

Loan modification is the systematic alteration of mortgage loan agreements that help those having problems making the payments by reducing interest rates, monthly payments or principal balances. Lending institutions could make one or more of these changes to relieve financial pressure on borrowers to prevent the condition of foreclosure. Loan modifications have been practiced in the United States since the 1930s. During the Great Depression, loan modification programs took place at the state level in an effort to reduce levels of loan foreclosures.

The Helping Families Save Their Homes Act of 2009 is an enacted public law in the United States. On May 20, 2009, the Senate bill was signed into law by President Barack Obama. The stated purpose of the act, a product of the 111th United States Congress, was to allow bankruptcy judges to modify mortgages on primary residences, among other purposes; however, that provision was dropped in the Senate and is not included in the version that was eventually signed into law. In addition, the bill amends the Hope for Homeowners Program as well as provide additional provisions to help borrowers avoid foreclosure.