Wat Bowaniwet Wihan Ratchaworawihan is a major Buddhist temple (wat) in Phra Nakhon district, Bangkok, Thailand. Being the residence of Nyanasamvara Suvaddhana, the late Supreme Patriarch of Thailand, it is the final resting place of two former kings of Chakri Dynasty: King Vajiravudh and King Bhumibol Adulyadej. The temple was established in 1824 by Mahasakti Pol Sep, viceroy during the reign of King Rama III.

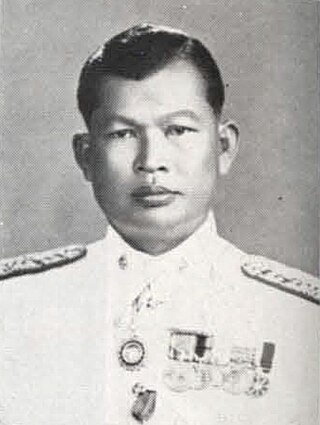

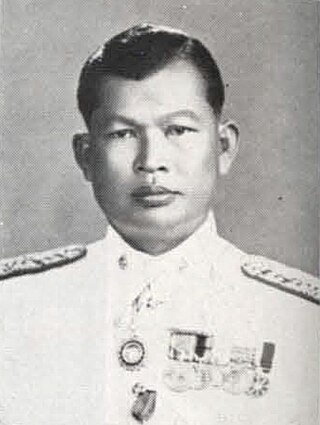

Admiral Sangad Chaloryu was a Thai admiral and politician who served as head of the National Administrative Reform Council (NARC), a military junta that ruled Thailand from 1976 to 1980.

A wat is a type of Buddhist and Hindu temple in Cambodia, Laos, East Shan State, Yunnan, the Southern Province of Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

Somdet Phra Bawonratchao Maha Sakdiphonlasep was the viceroy appointed by Nangklao as the titular heir to the throne as he was the uncle to the king.

Wat Mongkolratanaram is a Buddhist Thai temple on the bank of the Palm River in Tampa, Florida. It was founded in 1981 as well as dedicated and registered as a temple on 19 May 1981. Besides a temple, it acts as an education and support centre.

Wat Bueng Thonglang is a Buddhist temple in Bang Kapi District, Bangkok, Thailand. It was measured under Theravada School, Section of Maha Nikai. It is located at Lat Phrao 101 Road. The temple was founded in King Rama V period by Longpoo Puk who was ordained in Wat Suthatthepvararam, and was a student of Sangaraja Phea.

Thawathotsamat is a poem of 1,042 lines in Thai, probably composed in the late fifteenth century CE. The title is a Thai adaptation of the Pali-Sanskrit words dvā dasa māsa, two ten months. The male speaker laments over a lost lover through the course of one year, drawing on the seasonal weather for similes of his emotions. Both the speaker and beloved are addressed with royal forms. A late verse declares that the poem was written by a "young-king" with the help of three court poets. The work has sometimes been mistakenly classified as a treatise on Siamese royal ceremonies. The work is less studied and less well-known than other early works of Thai literature, partly because of the obscurity of its archaic language, and partly because of conservative concerns over its erotic passages. A new annotated Thai edition appeared in 2017.

The Kammatthana meditation tradition originally grew out of the Dhammayut reform movement, founded by Mongkut in the 1820s as an attempt to raise the bar for what was perceived as the "lax" Buddhist practice of the regional Buddhist traditions at the time. Mongkut's reforms were originally focused on scriptural study of the earliest extant Buddhist texts, revival of the dhutanga ascetic practices, and close adherence to the Buddhist Monastic Code. However, the Dhammayut began to have an increasing emphasis on meditation as the 19th century progressed. During this time, a newly ordained Mun Bhuridatto went to stay with Ajahn Sao Kantasīlo, who was then the abbot of a small meditation-oriented monastery on the outskirts of Ubon Ratchathani, a province in the predominantly Lao-speaking cultural region of Northeast Thailand known as Isan.

King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand died at the age of 88 on 13 October 2016, after a long illness. A year-long period of mourning was subsequently announced. A royal cremation ceremony took place over five days at the end of October 2017. The actual cremation, which was not broadcast on television, was held in the late evening of 26 October 2017. Following cremation his remains and ashes were taken to the Grand Palace and were enshrined at the Chakri Maha Phasat Throne Hall, the Royal Cemetery at Wat Ratchabophit and the Wat Bowonniwet Vihara Royal Temple. Following burial, the mourning period officially ended on midnight of 30 October 2017 and Thais resumed wearing colors other than black in public.

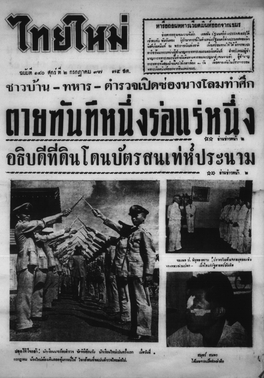

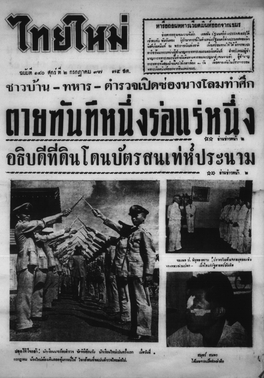

Thai Mai was a Thai daily newspaper. Its publication started at the end of 1930 (2473) and was in continuous operation as a daily newspaper in Thailand up into the 1950s. It was an early business venture of Lek Komet. Lek was in his late thirties in 1930. His first success in business was as a compradore with the Burley Company. He subsequently started Haang Komet (ห้างโกเมศ) and then went on to his own branded line of cosmetics. He sold that business and used the capital to develop other ventures. Thai Mai was an early one of those ventures. He had a partner in the Thai Mai startup, one Ek Wisakul, another successful compradore.

Thai funerals usually follow Buddhist funerary rites, with variations in practice depending on the culture of the region. People of certain religious and ethnic groups also have their own specific practices. Thai Buddhist funerals generally consist of a bathing ceremony shortly after death, daily chanting by Buddhist monks, and a cremation ceremony. Cremation is practised by most peoples throughout the country, with the major exceptions being ethnic Chinese, Muslims and Christians.

Thai royal funerals are elaborate events, organised as royal ceremonies akin to state funerals. They are held for deceased members of the royal family, and consist of numerous rituals which typically span several months to over a year. Featuring a mixture of Buddhist and animist beliefs, as well as Hindu symbolism, these rituals include the initial rites that take place after death, a lengthy period of lying-in-state, during which Buddhist ceremonies take place, and a final cremation ceremony. For the highest-ranking royalty, the cremation ceremonies are grand public spectacles, featuring the pageantry of large funeral processions and ornate purpose-built funeral pyres or temporary crematoria known as merumat or men. The practices date to at least the 17th century, during the time of the Ayutthaya Kingdom. Today, the cremation ceremonies are held in the royal field of Sanam Luang in the historic centre of Bangkok.

Bang Lamphu, also spelled Banglampoo or Banglamphu is a neighbourhood in Bangkok located in Phra Nakhon District. The history of the Bang Lamphu community dates to the establishment of the Rattanakosin Kingdom, or earlier. Bang Lamphu covers an area north of Phra Nakhon both inside and outside Rattanakosin Island from Phra Athit to Samsen Roads, which leads toward Dusit District. Most of the area of Bang Lamphu is in Talat Yot Subdistrict, with some spreading to various nearby subdistricts including Chana Songkhram, Bowon Niwet, Ban Phan Thom up till Wat Sam Phraya.

Phra Malai Kham Luang is the royal version of a Thai legendary poem of the Sri Lankan monk Arhat Maliyadeva, whose stories are popular in Thai Theravada Buddhism. The vernacular version is known as Phra Malai Klon Suat. Phra Malai is the subject of numerous palm-leaf manuscripts, folding books, and artworks. His story, which includes concepts such as reincarnation, merit, and Buddhist cosmology, was a popular part of Thai funeral practices in the nineteenth century.

Mom Luang Dej Snidvongs was a Thai honorary academic. He was the President of the Privy Council of Thailand to King Bhumibol Adulyadej and Governor of the Bank of Thailand in 1949 to 1952. He was given the title of Luang Dejsahakorn.

Wat Ratchapradit Sathit Mahasimaram Ratcha Wora Maha Viharn is a Buddhist temple in the Phra Nakhon District of Bangkok. Wat Ratchaparadit was designated a first-class royal monastery in 1915, making it one of the most significant temples in Thailand.

Wat Phra Si Mahathat Wora Maha Viharn is a Buddhist temple in the Bang Khen District of Bangkok. Construction began in 20 March 1941 in commemoration of the government victory over the Boworadet rebellion in 1933. Wat Phra Si Mahathat was designated a first-class royal monastery in 1942, making it one of the most significant temples in Thailand.

Thai typography concerns the representation of the Thai script in print and on displays, and dates to the earliest printed Thai text in 1819. The printing press was introduced by Western missionaries during the mid-nineteenth century, and the printed word became an increasingly popular medium, spreading modern knowledge and aiding reform as the country modernized. The printing of textbooks for a new education system and newspapers and magazines for a burgeoning press in the early twentieth century spurred innovation in typography and type design, and various styles of Thai typefaces were developed through the ages as metal type gave way to newer technologies. Modern media is now served by digital typography, and despite early obstacles including lack of copyright protection, the market now sees contributions by several type designers and digital type foundries.

Pavares Variyalongkorn was a Buddhist scholar, historian and a prince of the Chakri dynasty. A son of the Viceroy Maha Senanurak and Noi Lek, the prince became a monk in 1830 and was given the dharma name Paññāaggo. In 1851 he succeed Mongkut as the second abbot of Wat Bowonniwet Vihara, upon the latter's accession to the throne as king. In the same year he was elevated in princely rank and received a new name; Krom Muen Bowonrangsisuriphan. In 1873 he was once again elevated in princely rank and became Krom Phra Pavares Variyalongkorn. In 1891 he was appointed Supreme Patriarch by King Chulalongkorn. He remained in this position until his death in 1892.

Folding-book manuscripts are a type of writing material historically used in Mainland Southeast Asia, particularly in the areas of present-day Myanmar, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia. They are known as parabaik in Burmese, samut thai in Thai or samut khoi in Thai and Lao, phap sa in Northern Thai and Lao, and kraing in Khmer.