Aerodynamics is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dynamics and its subfield of gas dynamics, and is an important domain of study in aeronautics. The term aerodynamics is often used synonymously with gas dynamics, the difference being that "gas dynamics" applies to the study of the motion of all gases, and is not limited to air. The formal study of aerodynamics began in the modern sense in the eighteenth century, although observations of fundamental concepts such as aerodynamic drag were recorded much earlier. Most of the early efforts in aerodynamics were directed toward achieving heavier-than-air flight, which was first demonstrated by Otto Lilienthal in 1891. Since then, the use of aerodynamics through mathematical analysis, empirical approximations, wind tunnel experimentation, and computer simulations has formed a rational basis for the development of heavier-than-air flight and a number of other technologies. Recent work in aerodynamics has focused on issues related to compressible flow, turbulence, and boundary layers and has become increasingly computational in nature.

The Mach number, often only Mach, is a dimensionless quantity in fluid dynamics representing the ratio of flow velocity past a boundary to the local speed of sound. It is named after the Austrian physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach.

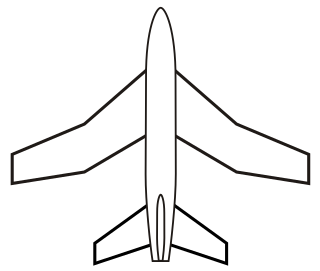

The Whitcomb area rule, named after NACA engineer Richard Whitcomb and also called the transonic area rule, is a design procedure used to reduce an aircraft's drag at transonic speeds which occur between about Mach 0.75 and 1.2. For supersonic speeds a different procedure called the supersonic area rule, developed by NACA aerodynamicist Robert Jones, is used.

A delta wing is a wing shaped in the form of a triangle. It is named for its similarity in shape to the Greek uppercase letter delta (Δ).

The sound barrier or sonic barrier is the large increase in aerodynamic drag and other undesirable effects experienced by an aircraft or other object when it approaches the speed of sound. When aircraft first approached the speed of sound, these effects were seen as constituting a barrier, making faster speeds very difficult or impossible. The term sound barrier is still sometimes used today to refer to aircraft approaching supersonic flight in this high drag regime. Flying faster than sound produces a sonic boom.

A swept wing is a wing angled either backward or occasionally forward from its root rather than perpendicular to the fuselage.

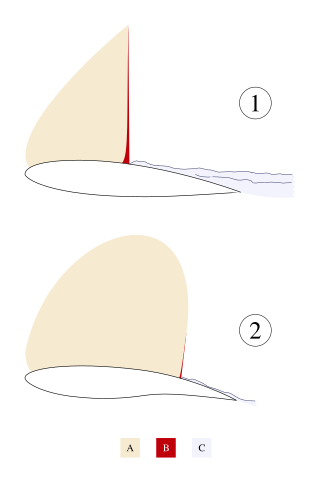

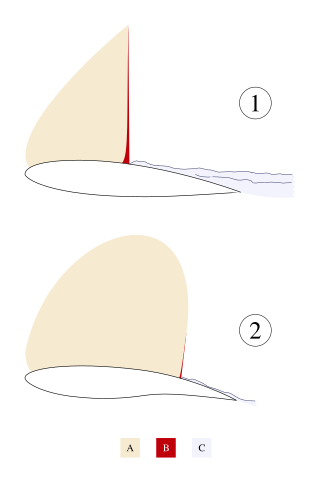

Transonic flow is air flowing around an object at a speed that generates regions of both subsonic and supersonic airflow around that object. The exact range of speeds depends on the object's critical Mach number, but transonic flow is seen at flight speeds close to the speed of sound, typically between Mach 0.8 and 1.2.

In aeronautics, wave drag is a component of the aerodynamic drag on aircraft wings and fuselage, propeller blade tips and projectiles moving at transonic and supersonic speeds, due to the presence of shock waves. Wave drag is independent of viscous effects, and tends to present itself as a sudden and dramatic increase in drag as the vehicle increases speed to the critical Mach number. It is the sudden and dramatic rise of wave drag that leads to the concept of a sound barrier.

Indicated airspeed (IAS) is the airspeed of an aircraft as measured by its pitot-static system and displayed by the airspeed indicator (ASI). This is the pilots' primary airspeed reference.

Hans Guido Mutke was a fighter pilot for the German Luftwaffe during World War II. He was born in Neisse, Upper Silesia.

Aircraft flight mechanics are relevant to fixed wing and rotary wing (helicopters) aircraft. An aeroplane, is defined in ICAO Document 9110 as, "a power-driven heavier than air aircraft, deriving its lift chiefly from aerodynamic reactions on surface which remain fixed under given conditions of flight".

A supercritical aerofoil is an airfoil designed primarily to delay the onset of wave drag in the transonic speed range.

Mach tuck is an aerodynamic effect whereby the nose of an aircraft tends to pitch downward as the airflow around the wing reaches supersonic speeds. This diving tendency is also known as tuck under. The aircraft will first experience this effect at significantly below Mach 1.

A supersonic aircraft is an aircraft capable of supersonic flight, that is, flying faster than the speed of sound. Supersonic aircraft were developed in the second half of the twentieth century. Supersonic aircraft have been used for research and military purposes, but only two supersonic aircraft, the Tupolev Tu-144 and the Concorde, ever entered service for civil use as airliners. Fighter jets are the most common example of supersonic aircraft.

In high-speed flight, the assumptions of incompressibility of the air used in low-speed aerodynamics no longer apply. In subsonic aerodynamics, the theory of lift is based upon the forces generated on a body and a moving gas (air) in which it is immersed. At airspeeds below about 260 kn, air can be considered incompressible in regards to an aircraft, in that, at a fixed altitude, its density remains nearly constant while its pressure varies. Under this assumption, air acts the same as water and is classified as a fluid.

The drag-divergence Mach number is the Mach number at which the aerodynamic drag on an airfoil or airframe begins to increase rapidly as the Mach number continues to increase. This increase can cause the drag coefficient to rise to more than ten times its low-speed value.

Coffin corner is the region of flight where a fast but subsonic fixed-wing aircraft's stall speed is near the critical Mach number, at a given gross weight and G-force loading. In this region of flight, it is very difficult to keep an airplane in stable flight. Because the stall speed is the minimum speed required to maintain level flight, any reduction in speed will cause the airplane to stall and lose altitude. Because the critical Mach number is the maximum speed at which air can travel over the wings without losing lift due to flow separation and shock waves, any increase in speed will cause the airplane to lose lift, or to pitch heavily nose-down, and lose altitude.

A subsonic aircraft is an aircraft with a maximum speed less than the speed of sound. The term technically describes an aircraft that flies below its critical Mach number, typically around Mach 0.8. All current civil aircraft, including airliners, helicopters, future passenger drones, personal air vehicles and airships, as well as many military types, are subsonic.

Aerodynamics is a branch of dynamics concerned with the study of the motion of air. It is a sub-field of fluid and gas dynamics, and the term "aerodynamics" is often used when referring to fluid dynamics

The crescent wing is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration in which a swept wing has a greater sweep angle on the inboard section than the outboard, giving the wing a crescent shape.