Private equity (PE) is stock in a private company that does not offer stock to the general public. In the field of finance, private equity is offered instead to specialized investment funds and limited partnerships that take an active role in the management and structuring of the companies. In casual usage, "private equity" can refer to these investment firms, rather than the companies in which they invest.

Venture capital (VC) is a form of private equity financing provided by firms or funds to startup, early-stage, and emerging companies, that have been deemed to have high growth potential or that have demonstrated high growth in terms of number of employees, annual revenue, scale of operations, etc. Venture capital firms or funds invest in these early-stage companies in exchange for equity, or an ownership stake. Venture capitalists take on the risk of financing start-ups in the hopes that some of the companies they support will become successful. Because startups face high uncertainty, VC investments have high rates of failure. Start-ups are usually based on an innovative technology or business model and often come from high technology industries such as information technology (IT) or biotechnology.

Gary Albert Doer is a former Canadian politician and diplomat from Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. He served as Canada's ambassador to the United States from 19 October 2009, to 3 March 2016. Doer previously served as the 20th premier of Manitoba from 1999 to 2009, leading a New Democratic Party government.

Fidelity Investments, formerly known as Fidelity Management & Research (FMR), is an American multinational financial services corporation based in Boston, Massachusetts. Established in 1946, the company is one of the largest asset managers in the world, with $5.8 trillion in assets under management, and $15.0 trillion in assets under administration, as of September 2024, Fidelity Investments operates a brokerage firm, manages a large family of mutual funds, provides fund distribution and investment advice, retirement services, index funds, wealth management, securities execution and clearance, asset custody, and life insurance.

Stuart Murray is a former politician from Manitoba, Canada. He served as leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Manitoba and leader of the opposition in the Manitoba legislature from 2000 to 2006. From 2006 until 2009, Murray was the President and Chief Executive Officer of the St. Boniface Hospital Research Foundation. He subsequently served as director and chief executive officer of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights from 2009 to 2014.

Jim Rondeau is a former politician in Manitoba, Canada. He served as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba from 1999 to 2016, and served as cabinet minister in the provincial governments of Gary Doer and Greg Selinger from 2003 to 2013. Rondeau is a member of the New Democratic Party. Rondeau did not seek re-election in the 2016 Manitoba election.

Drew Caldwell is a politician in Manitoba, Canada. He was a member of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba for the constituency of Brandon East from 1999 until 2016, serving as a Cabinet Minister in the governments of Gary Doer and Greg Selinger. Caldwell is a member of the New Democratic Party.

John Loewen is a businessman and politician in Manitoba, Canada. He served in the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba from 1999 to 2005 as a member of the Progressive Conservative Party, and campaigned for the House of Commons of Canada in 2006 and 2008 as a Liberal. He is the nephew of Bill and Shirley Loewen, prominent entrepreneurs and philanthropists in Winnipeg.

Heather Dorothy Stefanson is a Canadian former politician who served as the 24th premier of Manitoba from 2021 to 2023; the first woman in the province's history to hold that role.

Rebecca Catherine Barrett was an American-born Canadian politician. She served as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba from 1990 to 2003, and was a cabinet minister in the New Democratic Party (NDP) government of Gary Doer from 1999 to 2003.

Manitoba Finance is the department of finance for the Canadian province of Manitoba.

An institutional investor is an entity that pools money to purchase securities, real property, and other investment assets or originate loans. Institutional investors include commercial banks, central banks, credit unions, government-linked companies, insurers, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, charities, hedge funds, real estate investment trusts, investment advisors, endowments, and mutual funds. Operating companies which invest excess capital in these types of assets may also be included in the term. Activist institutional investors may also influence corporate governance by exercising voting rights in their investments. In 2019, the world's top 500 asset managers collectively managed $104.4 trillion in Assets under Management (AuM).

The Canada Life Assurance Company, commonly known as Canada Life (Canada-Vie), is a Canadian insurance and financial services company with its headquarters in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The current company is the result of the 2020 amalgamation of The Great-West Life Assurance Company, London Life Insurance Company and The Canada Life Assurance Company, along with their holding companies. The company is a wholly owned subsidiary of Great-West Lifeco.

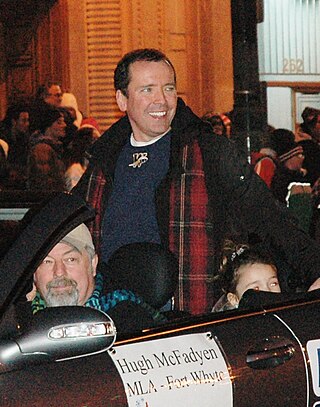

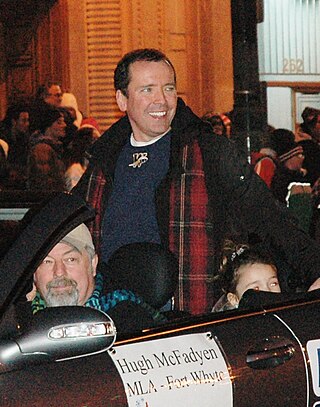

Hugh Daniel McFadyen is a lawyer and politician in Manitoba, Canada. From 2006 to 2012, he was the leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Manitoba, and Leader of the Opposition in the Manitoba legislature.

A labour-sponsored venture capital corporation(LSVCC), known alternately as labour-sponsored investment fund(LSIF) or simply retail venture capital (RVC), is a fund managed by investment professionals that invests in small to mid-sized Canadian companies. The Canadian federal government and some provincial governments offer tax credits to LSVCC investors to promote the growth of such companies.

Jon Singleton is a public servant in Manitoba, Canada. He is best known for his high-profile tenure as Auditor General of Manitoba from 1996 to 2006.

Peter Olfert is a Canadian labour leader in Manitoba, Canada. Olfert was president of the Manitoba Government and General Employees’ Union from 1986 to 2010. He has also served as a vice-president of the National Union of Public and General Employees.

Canad Corporation of Manitoba Ltd. is a Winnipeg-based hospitality company. It owns or operates ten hotels in Canada and one in the United States, with all but one of its properties operating under the Canad Inns Destination Centre branding.

The New Zealand Superannuation Fund is a sovereign wealth fund in New Zealand. New Zealand currently provides universal superannuation for people over 65 years of age and the purpose of the Fund is to partially pre-fund the future cost of the New Zealand Superannuation pension, which is expected to increase as a result of New Zealand's ageing population. The fund is a member of the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds and is therefore signed up to the Santiago Principles on best practice in managing sovereign wealth funds.

Fund governance refers to a system of checks and balances and work performed by the governing body (board) of an investment fund to ensure that the fund is operated not only in accordance with law, but also in the best interests of the fund and its investors. The objective of fund governance is to uphold the regulatory principles commonly known as the four pillars of investor protection that are typically promulgated through the investment fund regulation applicable in the jurisdiction of the fund. These principles vary by jurisdiction and in the US, the 1940 Act generally ensure that: (i) The investment fund will be managed in accordance with the fund's investment objectives, (ii) The assets of the investment fund will be kept safe, (iii) When investors redeem they will get their pro rata share of the investment fund's assets, (iv) The investment fund will be managed for the benefit of the fund's shareholders and not its service providers.