In quantum mechanics, the Hamiltonian of a system is an operator corresponding to the total energy of that system, including both kinetic energy and potential energy. Its spectrum, the system's energy spectrum or its set of energy eigenvalues, is the set of possible outcomes obtainable from a measurement of the system's total energy. Due to its close relation to the energy spectrum and time-evolution of a system, it is of fundamental importance in most formulations of quantum theory.

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. If m is an object's mass and v is its velocity, then the object's momentum p is:

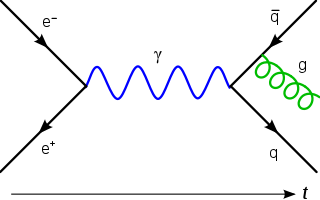

In particle physics, the Dirac equation is a relativistic wave equation derived by British physicist Paul Dirac in 1928. In its free form, or including electromagnetic interactions, it describes all spin-1/2 massive particles, called "Dirac particles", such as electrons and quarks for which parity is a symmetry. It is consistent with both the principles of quantum mechanics and the theory of special relativity, and was the first theory to account fully for special relativity in the context of quantum mechanics. It was validated by accounting for the fine structure of the hydrogen spectrum in a completely rigorous way. It has become vital in the building of the Standard Model.

The Schrödinger equation is a partial differential equation that governs the wave function of a quantum-mechanical system. Its discovery was a significant landmark in the development of quantum mechanics. It is named after Erwin Schrödinger, who postulated the equation in 1925 and published it in 1926, forming the basis for the work that resulted in his Nobel Prize in Physics in 1933.

In quantum chemistry and molecular physics, the Born–Oppenheimer (BO) approximation is the best-known mathematical approximation in molecular dynamics. Specifically, it is the assumption that the wave functions of atomic nuclei and electrons in a molecule can be treated separately, based on the fact that the nuclei are much heavier than the electrons. Due to the larger relative mass of a nucleus compared to an electron, the coordinates of the nuclei in a system are approximated as fixed, while the coordinates of the electrons are dynamic. The approach is named after Max Born and his 23-year-old graduate student J. Robert Oppenheimer, the latter of whom proposed it in 1927 during a period of intense fervent in the development of quantum mechanics.

In quantum physics, a wave function is a mathematical description of the quantum state of an isolated quantum system. The most common symbols for a wave function are the Greek letters ψ and Ψ. Wave functions are complex-valued. For example, a wave function might assign a complex number to each point in a region of space. The Born rule provides the means to turn these complex probability amplitudes into actual probabilities. In one common form, it says that the squared modulus of a wave function that depends upon position is the probability density of measuring a particle as being at a given place. The integral of a wavefunction's squared modulus over all the system's degrees of freedom must be equal to 1, a condition called normalization. Since the wave function is complex-valued, only its relative phase and relative magnitude can be measured; its value does not, in isolation, tell anything about the magnitudes or directions of measurable observables. One has to apply quantum operators, whose eigenvalues correspond to sets of possible results of measurements, to the wave function ψ and calculate the statistical distributions for measurable quantities.

Matter waves are a central part of the theory of quantum mechanics, being half of wave–particle duality. At all scales where measurements have been practical, matter exhibits wave-like behavior. For example, a beam of electrons can be diffracted just like a beam of light or a water wave.

In condensed matter physics, Bloch's theorem states that solutions to the Schrödinger equation in a periodic potential can be expressed as plane waves modulated by periodic functions. The theorem is named after the Swiss physicist Felix Bloch, who discovered the theorem in 1929. Mathematically, they are written

A continuity equation or transport equation is an equation that describes the transport of some quantity. It is particularly simple and powerful when applied to a conserved quantity, but it can be generalized to apply to any extensive quantity. Since mass, energy, momentum, electric charge and other natural quantities are conserved under their respective appropriate conditions, a variety of physical phenomena may be described using continuity equations.

In quantum mechanics, the particle in a one-dimensional lattice is a problem that occurs in the model of a periodic crystal lattice. The potential is caused by ions in the periodic structure of the crystal creating an electromagnetic field so electrons are subject to a regular potential inside the lattice. It is a generalization of the free electron model, which assumes zero potential inside the lattice.

In physics, specifically relativistic quantum mechanics (RQM) and its applications to particle physics, relativistic wave equations predict the behavior of particles at high energies and velocities comparable to the speed of light. In the context of quantum field theory (QFT), the equations determine the dynamics of quantum fields. The solutions to the equations, universally denoted as ψ or Ψ, are referred to as "wave functions" in the context of RQM, and "fields" in the context of QFT. The equations themselves are called "wave equations" or "field equations", because they have the mathematical form of a wave equation or are generated from a Lagrangian density and the field-theoretic Euler–Lagrange equations.

In physics, a free particle is a particle that, in some sense, is not bound by an external force, or equivalently not in a region where its potential energy varies. In classical physics, this means the particle is present in a "field-free" space. In quantum mechanics, it means the particle is in a region of uniform potential, usually set to zero in the region of interest since the potential can be arbitrarily set to zero at any point in space.

In solid-state physics, the nearly free electron model is a quantum mechanical model of physical properties of electrons that can move almost freely through the crystal lattice of a solid. The model is closely related to the more conceptual empty lattice approximation. The model enables understanding and calculation of the electronic band structures, especially of metals.

Surface states are electronic states found at the surface of materials. They are formed due to the sharp transition from solid material that ends with a surface and are found only at the atom layers closest to the surface. The termination of a material with a surface leads to a change of the electronic band structure from the bulk material to the vacuum. In the weakened potential at the surface, new electronic states can be formed, so called surface states.

In quantum mechanics, the probability current is a mathematical quantity describing the flow of probability. Specifically, if one thinks of probability as a heterogeneous fluid, then the probability current is the rate of flow of this fluid. It is a real vector that changes with space and time. Probability currents are analogous to mass currents in hydrodynamics and electric currents in electromagnetism. As in those fields, the probability current is related to the probability density function via a continuity equation. The probability current is invariant under gauge transformation.

In solid-state physics, the k·p perturbation theory is an approximated semi-empirical approach for calculating the band structure and optical properties of crystalline solids. It is pronounced "k dot p", and is also called the "k·p method". This theory has been applied specifically in the framework of the Luttinger–Kohn model, and of the Kane model.

Spin is an intrinsic form of angular momentum carried by elementary particles, and thus by composite particles such as hadrons, atomic nuclei, and atoms. Spin is quantized, and accurate models for the interaction with spin require relativistic quantum mechanics or quantum field theory.

Heat transfer physics describes the kinetics of energy storage, transport, and energy transformation by principal energy carriers: phonons, electrons, fluid particles, and photons. Heat is thermal energy stored in temperature-dependent motion of particles including electrons, atomic nuclei, individual atoms, and molecules. Heat is transferred to and from matter by the principal energy carriers. The state of energy stored within matter, or transported by the carriers, is described by a combination of classical and quantum statistical mechanics. The energy is different made (converted) among various carriers. The heat transfer processes are governed by the rates at which various related physical phenomena occur, such as the rate of particle collisions in classical mechanics. These various states and kinetics determine the heat transfer, i.e., the net rate of energy storage or transport. Governing these process from the atomic level to macroscale are the laws of thermodynamics, including conservation of energy.

Symmetries in quantum mechanics describe features of spacetime and particles which are unchanged under some transformation, in the context of quantum mechanics, relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum field theory, and with applications in the mathematical formulation of the standard model and condensed matter physics. In general, symmetry in physics, invariance, and conservation laws, are fundamentally important constraints for formulating physical theories and models. In practice, they are powerful methods for solving problems and predicting what can happen. While conservation laws do not always give the answer to the problem directly, they form the correct constraints and the first steps to solving a multitude of problems. In application, understanding symmetries can also provide insights on the eigenstates that can be expected. For example, the existence of degenerate states can be inferred by the presence of non commuting symmetry operators or that the non degenerate states are also eigenvectors of symmetry operators.

In quantum mechanics, a translation operator is defined as an operator which shifts particles and fields by a certain amount in a certain direction. It is a special case of the shift operator from functional analysis.