Dada or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century, with early centres in Zürich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire, founded by Hugo Ball with his companion Emmy Hennings, and in Berlin in 1917. New York Dada began c. 1915, and after 1920 Dada flourished in Paris. Dadaist activities lasted until the mid 1920s.

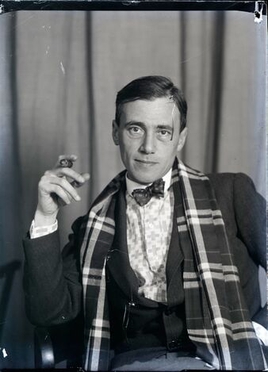

Tristan Tzara was a Romanian avant-garde poet, essayist and performance artist. Also active as a journalist, playwright, literary and art critic, composer and film director, he was known best for being one of the founders and central figures of the anti-establishment Dada movement. Under the influence of Adrian Maniu, the adolescent Tzara became interested in Symbolism and co-founded the magazine Simbolul with Ion Vinea and painter Marcel Janco.

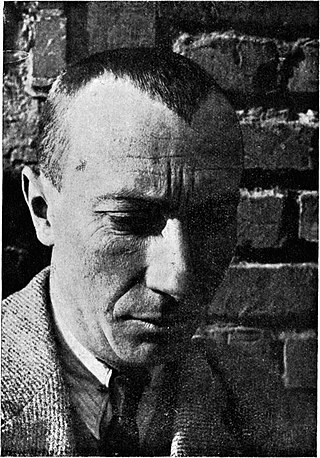

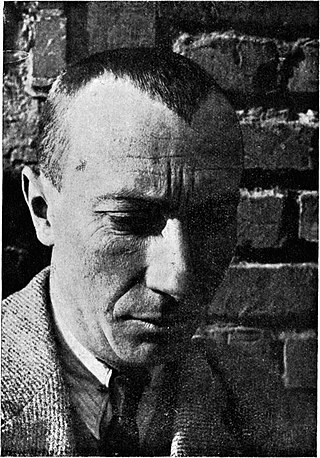

HansRichter was a German Dada painter, graphic artist, avant-garde film producer, and art historian. In 1965 he authored the book Dadaism about the history of the Dada movement. He was born in Berlin into a well-to-do family and died in Minusio, near Locarno, Switzerland.

Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp was a French painter, sculptor, chess player, and writer whose work is associated with Cubism, Dada, and conceptual art. He is commonly regarded, along with Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, as one of the three artists who helped to define the revolutionary developments in the plastic arts in the opening decades of the 20th century, responsible for significant developments in painting and sculpture. He has had an immense impact on 20th- and 21st-century art, and a seminal influence on the development of conceptual art. By the time of World War I, he had rejected the work of many of his fellow artists as "retinal", intended only to please the eye. Instead, he wanted to use art to serve the mind.

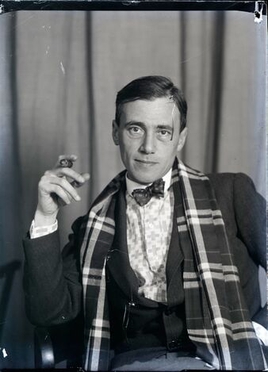

Francis Picabia was a French avant-garde painter, writer, filmmaker, magazine publisher, poet, and typographist closely associated with Dada.

Hans Peter Wilhelm Arp, better known as Jean Arp in English, was a German-French sculptor, painter, and poet. He was known as a Dadaist and an abstract artist.

Suzanne Duchamp-Crotti was a French Dadaist painter, collagist, sculptor, and draughtsman. Her work was significant to the development of Paris Dada and modernism and her drawings and collages explore fascinating gender dynamics. Due to the fact that she was a woman in the male prominent Dada movement, she was rarely considered an artist in her own right. She constantly lived in the shadows of her famous older brothers, who were also artists, or she was referred to as "the wife of." Her work in painting turns out to be significantly influential to the landscape of Dada in Paris and to the interests of women in Dada. She took a large role as an avant-garde artist, working through a career that spanned five decades, during a turbulent time of great societal change. She used her work to express certain subject matter such as personal concerns about modern society, her role as a modern woman artist, and the effects of the First World War. Her work often weaves painting, collage, and language together in complex ways.

Cabaret Voltaire was the name of a short-lived artistic nightclub in Zürich, Switzerland in 1916. It was founded by Hugo Ball, with his companion Emmy Hennings, in the back room of Holländische Meierei, Spiegelgasse 1, on February 5, 1916, as a cabaret for artistic and political purposes. Other founding members were Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp.

Johannes Theodor Baargeld was a pseudonym of Alfred Emanuel Ferdinand Grünwald, a German painter and poet who, together with Max Ernst, founded the Cologne Dada group. He also used the name Zentrodada in connection with Dada.

Sophie Henriette Gertrud Taeuber-Arp was a Swiss artist, painter, sculptor, textile designer, furniture and interior designer, architect, and dancer.

Events from the year 1916 in art.

Viking Eggeling was a Swedish avant-garde artist and filmmaker connected to dadaism, Constructivism, and abstract art and was one of the pioneers in absolute film and visual music. His 1924 film Diagonal-Symphonie is one of the seminal abstract films in the history of experimental cinema.

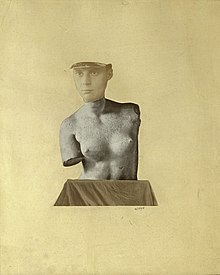

Object to Be Destroyed is a work by American artist Man Ray, originally created in 1923. The work consists of a metronome with a photograph of an eye attached to its swinging arm. After the piece was destroyed in 1957, later remakes in multiple copies were renamed Indestructible Object. Considered a "readymade" piece, in the style established by Marcel Duchamp, it employs an ordinary manufactured object, with little modification, as a work of art. Examples of the work are held in various public collections including Tate Modern London, MOMA New York and Reina Sofía, Madrid.

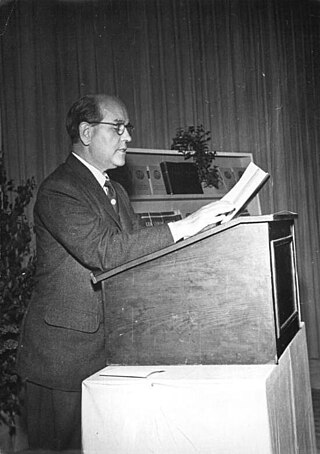

Michel Sanouillet was a French art historian and one of the foremost specialists of the Dada movement.

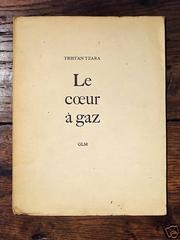

The Gas Heart or The Gas-Operated Heart is a French-language play by Romanian-born author Tristan Tzara. It was written as a series of non sequiturs and a parody of classical drama—it has three acts despite being short enough to qualify as a one-act play. A part-musical performance that features ballet numbers, it is one of the most recognizable plays inspired by the anti-establishment trend known as Dadaism. The Gas Heart was first staged in Paris, as part of the 1921 "Dada Salon" at the Galerie Montaigne.

Wieland Herzfelde was a German publisher and writer. He is particularly known for his links with German avant-garde art and Marxist thought, and was the brother of the photo montage artist John Heartfield, with whom he often worked.

New York Dada was a regionalized extension of Dada, an artistic and cultural movement between the years 1913 and 1923. Usually considered to have been instigated by Marcel Duchamp's Fountain exhibited at the first exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in 1917, and becoming a movement at the Cabaret Voltaire in February, 1916, in Zürich, the Dadaism as a loose network of artists spread across Europe and other countries, with New York becoming the primary center of Dada in the United States. The very word Dada is notoriously difficult to define and its origins are disputed, particularly amongst the Dadaists themselves.

Gabrièle Buffet-Picabia was a French art critic and writer affiliated with Dadaism. She was an organiser of the French resistance and the first wife of artist Francis Picabia.

Pierre de Massot was a French writer associated with the Dada and surrealist movements.