Benguet, officially the Province of Benguet, is a landlocked province of the Philippines located in the southern tip of the Cordillera Administrative Region in the island of Luzon. Its capital is La Trinidad.

The Cordillera Administrative Region, also known as the Cordillera Region and Cordillera, is an administrative region in the Philippines, situated within the island of Luzon. It is the only landlocked region in the insular country, bordered by the Ilocos Region to the west and southwest, and by the Cagayan Valley Region to the north, east, and southeast. It is the least populous region in the Philippines, with a population less than that of the city of Manila.

The Cordillera Central or Cordillera Range is a massive mountain range 320 km long north-south and 118 km east-west. The Cordillera mountain range is situated in the north-central part of the island of Luzon, in the Philippines. The mountain range encompasses all provinces of the Cordillera Administrative Region, as well as portions of eastern Ilocos Norte, eastern Ilocos Sur, eastern La Union, northeastern Pangasinan, western Nueva Vizcaya, and western Cagayan.

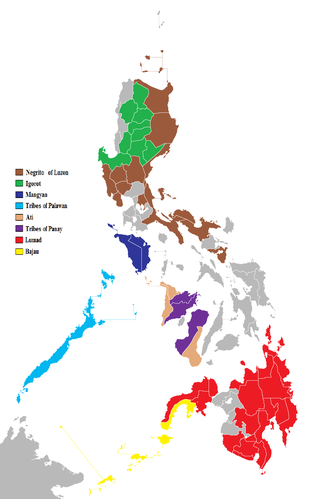

The indigenous peoples of the Cordillera Mountain Range of northern Luzon, Philippines, often referred to by the exonym Igorot people, or more recently, as the Cordilleran peoples, are an ethnic group composed of nine main ethnolinguistic groups whose domains are in the Cordillera Mountain Range, altogether numbering about 1.5 million people in the early 21st century.

Kankanaey is a South-Central Cordilleran language under the Austronesian family spoken on the island of Luzon in the Philippines primarily by the Kankanaey people. Alternate names for the language include Central Kankanaey, Kankanai, and Kankanay. It is widely used by Cordillerans, alongside Ilocano, specifically people from Mountain Province and people from the northern part of the Benguet Province. Kankanaey has a slight mutual intelligibility with the Ilocano language.

Hanging coffins are coffins which have been placed on cliffs. They are practiced by various cultures in China, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

Cervantes, officially the Municipality of Cervantes, is a 4th class municipality in the province of Ilocos Sur, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 19,449 people.

Bontoc, officially the Municipality of Bontoc, is a 2nd class municipality and capital of the province of Mountain Province, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 24,104 people.

Sagada, officially the Municipality of Sagada is a 5th class municipality in the province of Mountain Province, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 11,510 people.

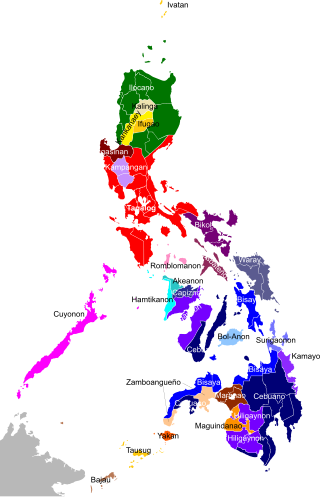

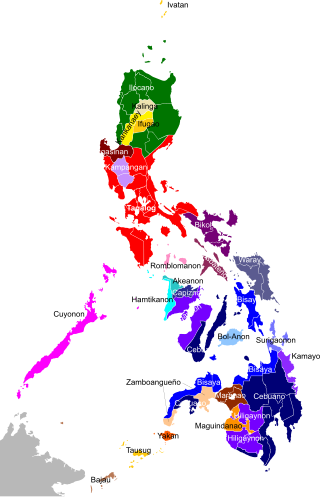

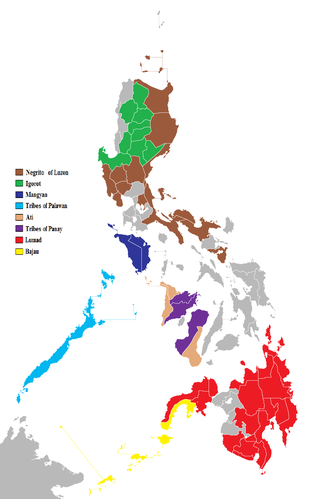

The Philippines is inhabited by more than 182 ethnolinguistic groups, many of which are classified as "Indigenous Peoples" under the country's Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997. Traditionally-Muslim peoples from the southernmost island group of Mindanao are usually categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are classified as Indigenous peoples or not. About 142 are classified as non-Muslim Indigenous People groups, and about 19 ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither indigenous nor moro. Various migrant groups have also had a significant presence throughout the country's history.

William Henry Scott was a historian of the Cordillera Central and pre-Hispanic Philippines.

The Gaddang language is spoken by up to 30,000 speakers in the Philippines, particularly along the Magat and upper Cagayan rivers in the Region II provinces of Nueva Vizcaya and Isabela and by overseas migrants to countries in Asia, Australia, Canada, Europe, in the Middle East, United Kingdom and the United States. Most Gaddang speakers also speak Ilocano, the lingua franca of Northern Luzon, as well as Tagalog and English. Gaddang is associated with the "Christianized Gaddang" people, and is closely related to the highland tongues of Ga'dang with 6,000 speakers, Yogad, Cagayan Agta with less than 1,000 and Atta with 2,000, and more distantly to Ibanag, Itawis, Isneg and Malaweg.

The Ifugao people are the ethnic group inhabiting Ifugao province in the Philippines. They reside in the municipalities of Lagawe, Aguinaldo, Alfonso Lista, Asipulo, Banaue, Hingyon, Hungduan, Kiangan, Lamut, Mayoyao, and Tinoc. The province is one of the smallest provinces in the Philippines with an area of only 251,778 hectares, or about 0.8% of the total Philippine land area. As of 1995, the population of the Ifugaos was counted to be 131,635. Although the majority of them are still in Ifugao province, some of them have moved to Baguio, where they work as woodcarvers, and to other parts of the Cordillera Region.

The indigenous peoples of the Philippines are ethnolinguistic groups or subgroups that maintain partial isolation or independence throughout the colonial era, and have retained much of their traditional pre-colonial culture and practices.

The pasiking is the indigenous basket-backpack found among the various ethno-linguistic groups of Northern Luzon in the Philippines. Pasiking designs have sacred allusions, although most are purely aesthetic. These artifacts, whether handwoven traditionally or with contemporary variations, are considered exemplars of functional basketry in the Philippines and among Filipinos.

The Kankanaey people are an Indigenous peoples of the Northern Philippines. They are part of the collective group of indigenous people known as the Igorot people.

The Bontoc ethnolinguistic group can be found in the central and eastern portions of Mountain Province, in the Philippines. Although some Bontocs of Natonin and Paracelis identify themselves as Balangaos, Gaddangs or Kalingas, the term "Bontoc" is used by linguists and anthropologists to distinguish speakers of the Bontoc language from neighboring ethnolinguistic groups. They formerly practiced head-hunting and had distinctive body tattoos.

St. Andrew the Apostle Parish, commonly known as Bacarra Church is a Roman Catholic church located in the municipality of Bacarra, Ilocos Norte, Philippines under the jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Laoag.

Anito, also spelled anitu, refers to ancestor spirits, nature spirits, and deities in the indigenous Philippine folk religions from the precolonial age to the present, although the term itself may have other meanings and associations depending on the Filipino ethnic group. It can also refer to carved humanoid figures, the taotao, made of wood, stone, or ivory, that represent these spirits. Anito is also sometimes known as diwata in certain ethnic groups.

Batok, batek, patik, or batik, among other names, are general terms for indigenous tattoos of the Philippines. Tattooing on both sexes was practiced by almost all ethnic groups of the Philippine Islands during the pre-colonial era. Like in other Austronesian groups, these tattoos were made traditionally with hafted tools tapped with a length of wood. Each ethnic group had specific terms and designs for tattoos, which are also often the same designs used in other artforms and decorations like in pottery and weaving. Tattoos range from being restricted only to certain parts of the body to covering the entire body. Tattoos were symbols of tribal identity and kinship, as well as bravery, beauty, and social or wealth status.