Related Research Articles

A dam is a barrier that stops or restricts the flow of surface water or underground streams. Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, human consumption, industrial use, aquaculture, and navigability. Hydropower is often used in conjunction with dams to generate electricity. A dam can also be used to collect or store water which can be evenly distributed between locations. Dams generally serve the primary purpose of retaining water, while other structures such as floodgates or levees are used to manage or prevent water flow into specific land regions.

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical ancient Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often considered one body of classical architecture. Roman architecture flourished in the Roman Republic and to an even greater extent under the Empire, when the great majority of surviving buildings were constructed. It used new materials, particularly Roman concrete, and newer technologies such as the arch and the dome to make buildings that were typically strong and well engineered. Large numbers remain in some form across the former empire, sometimes complete and still in use today.

Glanum was an ancient and wealthy city which still enjoys a magnificent setting below a gorge on the flanks of the Alpilles mountains. It is located about one kilometre south of the town of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

The Aniene, formerly known as the Teverone, is a 99-kilometer (62 mi) river in Lazio, Italy. It originates in the Apennines at Trevi nel Lazio and flows westward past Subiaco, Vicovaro, and Tivoli to join the Tiber in northern Rome. It formed the principal valley east of ancient Rome and became an important water source as the city's population expanded. The falls at Tivoli were noted for their beauty. Historic bridges across the river include the Ponte Nomentano, Ponte Mammolo, Ponte Salario, and Ponte di San Francesco, all of which were originally fortified with towers.

Shushtar is a city in the Central District of Shushtar County, Khuzestan province, Iran, serving as capital of both the county and the district.

Dara or Daras was an important East Roman fortress city in northern Mesopotamia on the border with the Sassanid Empire. Because of its great strategic importance, it featured prominently in the Roman-Persian conflicts. The former archbishopric remains a multiple Catholic titular see. Today, the village of Dara, in the Mardin Province occupies its location.

Ancient Roman technology is the collection of techniques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices which supported Roman civilization and made possible the expansion of the economy and military of ancient Rome.

The Cornalvo Dam is a Roman gravity dam built to supply water to the Roman colonia of Emerita Augusta –present-day Mérida, Spain–, capital of the Roman province of Lusitania. It was built in the 1st–2nd century AD as part of the infrastructure which supplied water to the city. The earth dam Roman concrete and stone cladding on the water face is still in use.

The Proserpina Dam is a Roman gravity dam built to supply water to the Roman colonia of Emerita Augusta –present-day Mérida, Spain–, capital of the Roman province of Lusitania. It was built in the 1st–2nd century AD as part of the infrastructure which supplied water to the city through the aqueduct of the Miracles. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the aqueduct fell into decay, but the earth dam with retaining wall is still in use.

The Alcantarilla Dam is a Roman gravity dam built to supply water to the Roman city of Toletum –present-day Toledo, Spain–, in the Roman province of Hispania Tarraconensis. It was built in the 2nd century BC on a tributary of the River Tagus. Currently in ruins, it is located in present-day Mazarambroz (Toledo). It is believed to be the oldest dam in Spain, and is possibly the oldest known Roman dam.

The Esparragalejo Dam was a Roman multiple arch buttress dam at Esparragalejo, Badajoz province, Extremadura, Spain. Dating to the 1st century AD, it is the earliest known multiple arch dam.

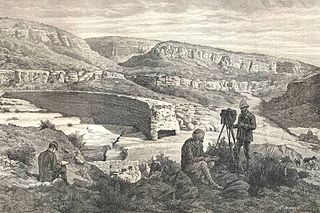

The Glanum Dam, also known as the Vallon de Baume dam, was a Roman arch dam built to supply water to the Roman town of Glanum, the remains of which stand outside the town of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in Southern France. It was situated south of Glanum, in a gorge that cut into the hills of the Alpilles in the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis. Dating to the 1st century BC, it was the earliest known dam of its kind. The remains of the dam were destroyed during the construction of a modern replacement in 1891, which now facilitates the supply of water to Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in the Bouches-du-Rhône region of France.

The Subiaco Dams were a group of three Roman gravity dams at Subiaco, Lazio, Italy, devised as pleasure lakes for Emperor Nero. The biggest one was the highest dam in the Roman Empire, and even in the world until its accidental destruction in 1305.

The Kasserine Dam was a Roman dam at Kasserine, Tunisia. The curved structure which dates to the 2nd century AD is variously classified as arch-gravity dam or gravity dam.

The Lake Homs Dam, also known as Qattinah Dam, is a Roman-built dam near the city of Homs, Syria, which is in use to this day.

The Muro Dam was a Roman dam in Portugal. Located near the eastern municipality of Campo Maior, it is the largest surviving ancient dam in the country south of the Tagus river.

The Shushtar Historical Hydraulic System is a complex irrigation system of the island city Shushtar from the Sassanid era. It consists of 13 dams, bridges, canals and structures which work together as a hydraulic system.

The Band-e Kaisar, Pol-e Kaisar, Bridge of Valerian or Shadirwan was an ancient arch bridge in the city of Shushtar, Khuzestan province, Iran, and the first in the country to combine it with a dam. Built by the Sassanids during the 3rd century CE, using Roman prisoners of war as the workforce, it is the easternmost example of Roman bridge design and Roman dam. Its dual-purpose design exerted a profound influence on Iranian civil engineering and was instrumental in developing Sassanid water management techniques.

References

- ↑ Smith 1971 , pp. 54f.; Schnitter 1987a , p. 13; Schnitter 1987b , p. 80; Hodge 1992 , p. 92; Hodge 2000 , p. 332, fn. 2

- 1 2 3 4 Garbrecht & Vogel 1991 , pp. 266–270

- ↑ Smith 1971 , pp. 54f.; Schnitter 1978 , p. 32; Schnitter 1987a , p. 13; Schnitter 1987b , p. 80; Hodge 1992 , p. 92; Hodge 2000 , p. 332, fn. 2

- ↑ Smith 1971 , pp. 53f.

- ↑ Garbrecht 2004 , p. 130

- ↑ Garbrecht & Vogel 1991 , p. 270