Related Research Articles

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, responding to stimuli, providing structure to cells and organisms, and transporting molecules from one location to another. Proteins differ from one another primarily in their sequence of amino acids, which is dictated by the nucleotide sequence of their genes, and which usually results in protein folding into a specific 3D structure that determines its activity.

The proteome is the entire set of proteins that is, or can be, expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism at a certain time. It is the set of expressed proteins in a given type of cell or organism, at a given time, under defined conditions. Proteomics is the study of the proteome.

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein, after synthesis by a ribosome as a linear chain of amino acids, changes from an unstable random coil into a more ordered three-dimensional structure. This structure permits the protein to become biologically functional.

Proteomics is the large-scale study of proteins. Proteins are vital macromolecules of all living organisms, with many functions such as the formation of structural fibers of muscle tissue, enzymatic digestion of food, or synthesis and replication of DNA. In addition, other kinds of proteins include antibodies that protect an organism from infection, and hormones that send important signals throughout the body.

Small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) is an experimental technique that uses elastic neutron scattering at small scattering angles to investigate the structure of various substances at a mesoscopic scale of about 1–100 nm.

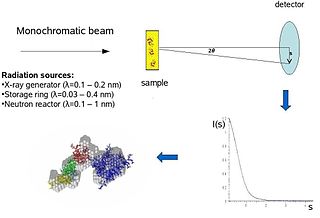

Biological small-angle scattering is a small-angle scattering method for structure analysis of biological materials. Small-angle scattering is used to study the structure of a variety of objects such as solutions of biological macromolecules, nanocomposites, alloys, and synthetic polymers. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) are the two complementary techniques known jointly as small-angle scattering (SAS). SAS is an analogous method to X-ray and neutron diffraction, wide angle X-ray scattering, as well as to static light scattering. In contrast to other X-ray and neutron scattering methods, SAS yields information on the sizes and shapes of both crystalline and non-crystalline particles. When used to study biological materials, which are very often in aqueous solution, the scattering pattern is orientation averaged.

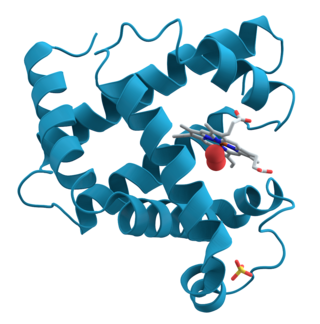

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers – specifically polypeptides – formed from sequences of amino acids, which are the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid monomer may also be called a residue, which indicates a repeating unit of a polymer. Proteins form by amino acids undergoing condensation reactions, in which the amino acids lose one water molecule per reaction in order to attach to one another with a peptide bond. By convention, a chain under 30 amino acids is often identified as a peptide, rather than a protein. To be able to perform their biological function, proteins fold into one or more specific spatial conformations driven by a number of non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, Van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic packing. To understand the functions of proteins at a molecular level, it is often necessary to determine their three-dimensional structure. This is the topic of the scientific field of structural biology, which employs techniques such as X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and dual polarisation interferometry, to determine the structure of proteins.

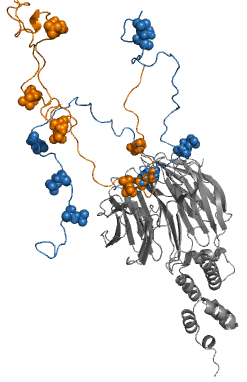

In molecular biology, an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) is a protein that lacks a fixed or ordered three-dimensional structure, typically in the absence of its macromolecular interaction partners, such as other proteins or RNA. IDPs range from fully unstructured to partially structured and include random coil, molten globule-like aggregates, or flexible linkers in large multi-domain proteins. They are sometimes considered as a separate class of proteins along with globular, fibrous and membrane proteins.

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

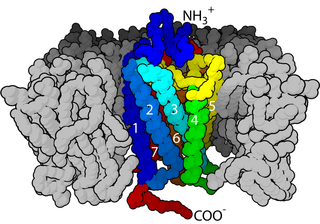

Arrestins are a small family of proteins important for regulating signal transduction at G protein-coupled receptors. Arrestins were first discovered as a part of a conserved two-step mechanism for regulating the activity of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in the visual rhodopsin system by Hermann Kühn, Scott Hall, and Ursula Wilden and in the β-adrenergic system by Martin J. Lohse and co-workers.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) is a small-angle scattering technique by which nanoscale density differences in a sample can be quantified. This means that it can determine nanoparticle size distributions, resolve the size and shape of (monodisperse) macromolecules, determine pore sizes, characteristic distances of partially ordered materials, and much more. This is achieved by analyzing the elastic scattering behaviour of X-rays when travelling through the material, recording their scattering at small angles. It belongs to the family of small-angle scattering (SAS) techniques along with small-angle neutron scattering, and is typically done using hard X-rays with a wavelength of 0.07 – 0.2 nm. Depending on the angular range in which a clear scattering signal can be recorded, SAXS is capable of delivering structural information of dimensions between 1 and 100 nm, and of repeat distances in partially ordered systems of up to 150 nm. USAXS can resolve even larger dimensions, as the smaller the recorded angle, the larger the object dimensions that are probed.

Cell surface receptors are receptors that are embedded in the plasma membrane of cells. They act in cell signaling by receiving extracellular molecules. They are specialized integral membrane proteins that allow communication between the cell and the extracellular space. The extracellular molecules may be hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, growth factors, cell adhesion molecules, or nutrients; they react with the receptor to induce changes in the metabolism and activity of a cell. In the process of signal transduction, ligand binding affects a cascading chemical change through the cell membrane.

In molecular biology, proteins are generally thought to adopt unique structures determined by their amino acid sequences. However, proteins are not strictly static objects, but rather populate ensembles of conformations. Transitions between these states occur on a variety of length scales and time scales , and have been linked to functionally relevant phenomena such as allosteric signaling and enzyme catalysis.

Anna Elizabeth Rhoades is a molecular biophysicist at University of Pennsylvania. She is known for pioneering studies of protein folding using single-molecule techniques.

Fuzzy complexes are protein complexes, where structural ambiguity or multiplicity exists and is required for biological function. Alteration, truncation or removal of conformationally ambiguous regions impacts the activity of the corresponding complex. Fuzzy complexes are generally formed by intrinsically disordered proteins. Structural multiplicity usually underlies functional multiplicity of protein complexes following a fuzzy logic. Distinct binding modes of the nucleosome are also regarded as a special case of fuzziness.

A thermal shift assay (TSA) measures changes in the thermal denaturation temperature and hence stability of a protein under varying conditions such as variations in drug concentration, buffer formulation, redox potential, or sequence mutation. The most common method for measuring protein thermal shifts is differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). DSF methodology includes techniques such as nanoDSF, which relies on the intrinsic fluorescence from native tryptophan or tyrosine residues, and Thermofluor, which utilizes extrinsic fluorogenic dyes.

In computational chemistry, conformational ensembles, also known as structural ensembles, are experimentally constrained computational models describing the structure of intrinsically unstructured proteins. Such proteins are flexible in nature, lacking a stable tertiary structure, and therefore cannot be described with a single structural representation. The techniques of ensemble calculation are relatively new on the field of structural biology, and are still facing certain limitations that need to be addressed before it will become comparable to classical structural description methods such as biological macromolecular crystallography.

G. Marius Clore MAE, FRSC, FMedSci, FRS is a British-born, Anglo-American molecular biophysicist and structural biologist. He was born in London, U.K. and is a dual U.S./U.K. Citizen. He is a Member of the National Academy of Sciences, a Fellow of the Royal Society, a Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences, a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a NIH Distinguished Investigator, and the Chief of the Molecular and Structural Biophysics Section in the Laboratory of Chemical Physics of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the U.S. National Institutes of Health. He is known for his foundational work in three-dimensional protein and nucleic acid structure determination by biomolecular NMR spectroscopy, for advancing experimental approaches to the study of large macromolecules and their complexes by NMR, and for developing NMR-based methods to study rare conformational states in protein-nucleic acid and protein-protein recognition. Clore's discovery of previously undetectable, functionally significant, rare transient states of macromolecules has yielded fundamental new insights into the mechanisms of important biological processes, and in particular the significance of weak interactions and the mechanisms whereby the opposing constraints of speed and specificity are optimized. Further, Clore's work opens up a new era of pharmacology and drug design as it is now possible to target structures and conformations that have been heretofore unseen.

Rohit Pappu is an Indian-born computational and molecular biophysicist. He is the Gene K. Beare Distinguished Professor of Engineering and the director of the Center for Biomolecular Condensates (CBC) at Washington University in St. Louis.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Perdigão, Nelson; Rosa, Agostinho (2019). "Dark Proteome Database: Studies on Dark Proteins". High-Throughput. 8 (2): 8. doi: 10.3390/ht8020008 . PMC 6630768 . PMID 30934744.

- 1 2 Perdigão, Nelson; et al. (2015). "Unexpected features of the dark proteome". PNAS. 112 (52): 15898–15903. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11215898P. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508380112 . PMC 4702990 . PMID 26578815.

- ↑ Ross, Jennifer L. (2016). "The Dark Matter of Biology". Biophysical Journal. 111 (5): 909–916. Bibcode:2016BpJ...111..909R. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2016.07.037. PMC 5018137 . PMID 27602719.

- ↑ Bhowmick, Asmit; Brookes, David H.; Yost, Shane R.; Dyson, H. Jane; Forman-Kay, Julie D.; Gunter, Daniel; Head-Gordon, Martin; Hura, Gregory L.; Pande, Vijay S.; Wemmer, David E.; Wright, Peter E.; Head-Gordon, Teresa (2016). "Finding Our Way in the Dark Proteome". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 138 (31): 9730–9742. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b06543. PMC 5051545 . PMID 27387657.