Legacy

British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli wrote the 1833 novel The Wondrous Tale of Alroy based on David Alroy and his revolt.

David Alroy or Alrui (Arabic : داود ابن الروحي, [1] Kurdish : داود ئەلۆی, Hebrew : דָּוִד אַלְרוֹאִי, fl. 1160), also known as Ibn ar-Ruhi and David El-David, was a Jewish Messiah claimant born in Amadiya, Iraq under the name Menaḥem ben Solomon (Hebrew : מְנַחֵם בֵּן שְׁלֹמֹה). David Alroy studied Torah and Talmud under Hasdai the Exilarch, and Ali, the head of the Academy in Baghdad. [2] He was also well-versed in Muslim literature and known as a worker of magic.

The caliphate in the days of Alroy was in a chaotic state. The Crusades had caused a general condition of unrest and a weakening of the authority of the sultans of Asia Minor and Persia. Defiant chieftains set up small independent states and heavy poll taxes were levied on all males above the age of fifteen. [3]

David Alroy led an uprising against Seljuk Sultan Muktafi and called upon the Jewish community to follow him to Jerusalem, where he would be their king and free the Jews from the hands of the Muslims. Alroy recruited supporters in the mountains of Chaftan, and sent letters to Mosul, Baghdad, and other towns, proclaiming his divine mission. He was born Menaḥem ben Solomon, but adopted the name "David Alroy" ("Alroy" possibly meaning "the inspired one") when he began claiming to be the Messiah. [4]

He was able to convince many Jewish people to join him and Alroy soon found himself with a considerable following. He resolved to attack the citadel of his native town, Amadiya, and directed his supporters to assemble in that city, with swords and other weapons concealed under their robes, and to give, as a pretext for their presence, their desire to study the Talmud. [5]

What followed is uncertain, for the sources of the life of Alroy each tell a different tale in which events are interwoven with legend. It is believed that Alroy and his followers were defeated, and Alroy was put to death. Despite Alroy's death, Jewish communities in Iran, particularly in Tabriz, Khoy and Maragheh continued to regard David Alroy as their messiah according to mathematician and historian Al-Samawal al-Maghribi. [6]

Benjamin of Tudela relates that the news of Alroy's revolt reached the ears of the Sultan, who sent for him. "Art thou the King of the Jews?" asked the Muslim sovereign, to which Alroy replied, "I am." [7] The Sultan thereupon cast him into prison in Tabaristan. Three days later, while the Sultan and his council were engaged in considering Alroy's rebellion, he suddenly appeared in their midst, having miraculously made his escape from prison. The Sultan at once ordered Alroy's rearrest; but, using magic, he made himself invisible and left the palace. Guided by the voice of Alroy the Sultan and his nobles followed him to the banks of a river, where, having made himself visible, he was seen to cross the water on a shawl, and made his escape with ease. On the same day he returned to Amadia, a journey which ordinarily took ten days, and related the story to his followers.

The Sultan threatened to put the Jews of his dominion to the sword if Alroy did not surrender, and the Jewish authorities in Baghdad pressed Alroy to abandon his messianic aspirations. From Mosul also an appeal was made to him by Zakkai and Joseph Barihan Alfalaḥ, the leaders of the Jewish community; but all in vain. The governor of Amadia, Saïf al-Din, bribed his father-in-law to assassinate him, and the revolt was brought to an end. The Jews of Persia had considerable difficulty in appeasing the wrath of the Sultan, and were obliged to pay a large indemnity.

Alroy's death did not entirely destroy the belief in his mission. Two impostors came to Bagdad and announced that upon a certain night they were all commanded to commence a flight through the air from Bagdad to Jerusalem, and, in the meantime, the followers of Alroy were to give their property into the charge of these two messengers from their dead leader. For many years afterward, a sect of Menaḥemites, as they were termed, continued to revere the memory of Alroy.

The principal source of the life of Alroy is Benjamin of Tudela's Travels. [8] This version is followed in its main outlines by Solomon ibn Verga, in his Shebeṭ Yehudah. [9] Ibn Verga states, on the authority of Maimonides, that when asked for a proof that he was truly the Messiah, Alroy (or David El-David, as Ibn Verga and David Gans in his ẒemaḦ David call him) replied, "Cut off my head and I shall yet live." David Gans, Gedaliah ibn Yahya (in his Shalshelet ha-Ḳabbalah), who calls him David Almusar, and R. Joseph ben Isaac Sambari closely follow Benjamin of Tudela's version. [10] The name Menahem ibn Alruhi ("the inspired one"), and the concluding episode of the imposters of Baghdad, are derived from the contemporaneous chronicle of the apostate, Samuel ibn Abbas. [11] The name Menahem (i.e., the comforter) was a common Messianic appellation. The name Alroy is probably identical with Alruhi. [12]

British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli wrote the 1833 novel The Wondrous Tale of Alroy based on David Alroy and his revolt.

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of mashiach, messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a mashiach is a king or High Priest traditionally anointed with holy anointing oil.

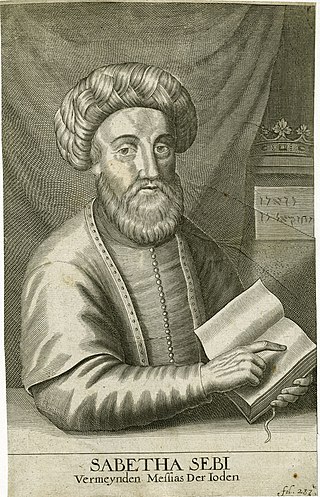

Sabbatai Zevi was an Ottoman Jewish mystic, and ordained rabbi from Smyrna. His family origins may have been Ashkenazi or Spanish. Active throughout the Ottoman Empire, Zevi claimed to be the long-awaited Jewish Messiah and founded the Sabbatean movement.

Ibn Tibbon is a family of Jewish rabbis and translators that lived principally in Provence in the 12th and 13th centuries.

The Davidic line or House of David is the lineage of the Israelite king David. In Judaism it is based on texts from the Hebrew Bible and through the succeeding centuries based on later traditions.

Hasdai ibn Shaprut born about 915 at Jaén, Spain; died about 970 at Córdoba, Andalusia, was a Jewish scholar, physician, diplomat, and patron of science.

Benjamin of Tudela, also known as Benjamin ben Jonah, was a medieval Jewish traveler who visited Europe, Asia, and Africa in the twelfth century. His vivid descriptions of western Asia preceded those of Marco Polo by a hundred years. With his broad education and vast knowledge of languages, Benjamin of Tudela is a major figure in medieval geography and Jewish history.

Ukbara (عكبرا) was a medieval city on the left bank of the Tigris between Samarra and Baghdad. The Tigris has changed course since, and its ruins now lie some distance from the river.

Amedi or Amadiye is a town in the Duhok Governorate of Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It is built on a mesa in the broader Great Zab river valley. Amedi is known for its celebrations of Newroz.

Menahem ben Saruq was a Spanish-Jewish philologist of the tenth century CE. He was a skilled poet and polyglot. He was born in Tortosa around 920 and died around 970 in Cordoba. Menahem produced an early dictionary of the Hebrew language. For a time he was the assistant of the great Jewish statesman Hasdai ibn Shaprut, and was involved in both literary and diplomatic matters; his dispute with Dunash ben Labrat, however, led to his downfall.

Solomon ibn Verga or Salomón ben Verga was a Spanish historian, physician, and author of the Shevet Yehudah.

Judah ibn Verga was a Sefardic historian, kabbalist, perhaps also mathematician, and astronomer of the 15th century. He was born at Seville and was the uncle of Solomon ibn Verga, author of the Scepter of Judah. It is this work that furnishes some details of ibn Verga's life.

Sefer Zerubavel, also called the Book of Zerubbabel or the Apocalypse of Zerubbabel, is a medieval Hebrew-language apocalypse written at the beginning of the seventh century CE in the style of biblical visions placed into the mouth of Zerubbabel, the last descendant of the Davidic line to take a prominent part in Israel's history, who laid the foundation of the Second Temple in the sixth century BCE. The enigmatic postexilic biblical leader receives a revelatory vision outlining personalities and events associated with the restoration of Israel, the End of Days, and the establishment of the Third Temple.

Alroy may refer to:

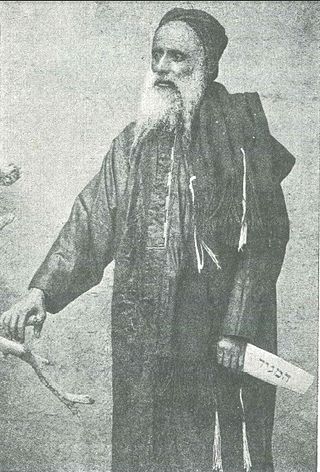

Rabbi Hayyim Habshush was a coppersmith by trade, and a noted nineteenth-century historiographer of Yemenite Jewry. He also served as a guide for the Jewish-French Orientalist and traveler Joseph Halévy. After his journey with Halévy in 1870, he was employed by Eduard Glaser and other later travellers to copy inscriptions and to collect old books.

The history of the Jews in Tudela, Spain goes back well over one thousand years.

David Solomon Sassoon, was a bibliophile and grandson of 19th century Baghdadi Jewish community leader David Sassoon.

The Wondrous Tale of Alroy is the sixth novel written by Benjamin Disraeli, who would later become a Prime Minister of Britain. Originally published in 1833, a "new edition” was published in 1834, a heavily revised edition in 1846 entitled Alroy: A Romance and another in 1871 based on that. It is a fictionalised account of the life of David Alroy. Its significance lies in its portrayal of Disraeli's "ideal ambition" and for its being his only novel with a distinctive Jewish subject. Cecil Roth described it as perhaps the earliest Jewish historical novel and Adam Kirsch as "a significant proto-Zionist text". Philip Rieff described an answer by Alroy as "perhaps one of the earliest Zionist perorations given in Western literature".

Abū Ṭāhir Abraham ben Mazhir was head of the remnant of the Palestinian Gaonate in Damascus in the first half of the 12th century.