Related Research Articles

Freemasonry was introduced by the Dutch to what is today Indonesia during the VOC era in the 18th century, and spread throughout the Dutch East Indies during a wave of westernisation in the 19th century. Freemasons originally only included Europeans and Indo-Europeans, but later also indigenous people with a Western education.

The Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad was one of the leading and largest daily newspapers in the Dutch East Indies. It was based in Batavia on Java, but read throughout the archipelago. It was founded by the famous Dutch newspaperman and author P. A. Daum in 1885 and existed to 1957.

Victor Ido is the main alias of the Indo (Eurasian) Dutch language writer and journalist Hans van de Wall. Born in Surabaya, Dutch East Indies from a Dutch father and Indo (Eurasian) mother. Ido was the Art Editor of P.A.Daum's Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad and later the Chief Editor of newspaper Batavia's Handelsblad as well as an accomplished musician (organist).

De Stem des Bloeds, also known as Njai Siti, is a 1930 film from the Dutch East Indies. It was directed by Ph. Carli and starred Annie Krohn, Sylvain Boekebinder, Vally Lank, and Jan Kruyt. The film follows a man and his mistress who reunite after their son and step-daughter unwittingly fall in love. The black-and-white film, which may now be lost, was tinted different colours for certain scenes. It was released in early 1930 to commercial success, although critical opinion was mixed.

Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië was a Dutch-language newspaper published on the island of Java in the Dutch East Indies. Originally called De Indische Courant, it was published in Batavia from 1895 or 1896 to 1900 until it was renamed. One of the paper's contributors was Dutch author and critic of the colonial system Multatuli.

The Suikerbond was a trade union for European workers in the sugar industry in the Dutch East Indies. The organization was founded on 14 March 1907 in Surabaya, as the Bond van Geëmployeerden in de Suikerindustrie in Nederlandsch-Indië. One of the two strongest unions for Europeans, in the early 1920s, during a wave of strikes by factory workers, the Suikerbond had been "bought off" by the sugar industry which had raised wages for European workers. In 1921 the organization founded its own newspaper, De Indische Courant, which was run by the union's president, W. Burger, and appears in two editions on the island of Java; initially leaning social-democratic, under pressure from union members a more conservative editor in chief was installed. By 1922 the organization numbered over 3800 members and had a strike fund of a half a million guilders.

Soeara Berbisa is a 1941 film from the Dutch East Indies. Produced by Ang Hock Liem for Union Films and directed by R Hu, this black-and-white film stars Raden Soekarno, Ratna Djoewita, Oedjang, and Soehaena. The story, written by Djojopranoto, follows two young men who compete for the affections of a woman before learning that they are long-lost brothers.

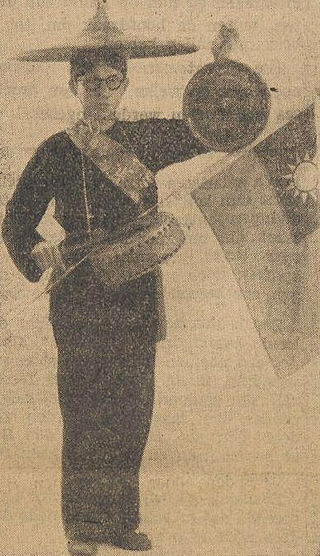

Louis Victor Wijnhamer, better known as Pah Wongso, was an Indo social worker popular within the ethnic Chinese community of the Dutch East Indies, and subsequently Indonesia. Educated in Semarang and Surabaya, Pah Wongso began his social work in the early 1930s, using traditional arts such as wayang golek to promote such causes as monogamy and abstinence. By 1938, he had established a school for the poor, and was raising money for the Red Cross to send aid to China.

The Bank of Java was a note-issuing bank in the Dutch East Indies, founded in 1828, and nationalized in 1951 by the government of Indonesia to become the newly independent country’s central bank, later renamed Bank Indonesia. For more than a century, the Bank of Java was the central institution of the Dutch East Indies’ financial system, alongside the “big three” commercial banks. It was both a note-issuing bank and a commercial bank.

Petrus Hendrik Willem "Peter" Sitsen was a military officer, building contractor and public servant in colonial Indonesia. He was the architect of Indonesia's industralisation policies during 1937–1942 and 1946–1950.

Tjahaja Timoer was a Malay-language Peranakan newspaper printed in Malang, Dutch East Indies, from 1907 to 1942.

Parada Harahap was an important journalist and writer from the late colonial period and early independence era in Indonesia. In the 1930s, he was called the "king of the Java press". He pioneered a new kind of politically neutral Malay language newspaper in the 1930s which would cater to the rising middle class of the Indies.

Algemeen handelsblad voor Nederlandsch-Indië was a Dutch language newspaper which was published in Semarang, Dutch East Indies from 1924 to 1942.

Evert Jansen was a newspaper editor, journalist and politician from the Dutch East Indies. From the 1910s to the 1940s, he was editor of a number of major papers including De Locomotief, Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, Algemeen handelsblad voor Nederlandsch-Indië, and De Indische Courant.

Selompret Melajoe was one of the first Malay language newspapers to publish in the Dutch East Indies. It was printed in Semarang, Central Java from 1860 to 1920.

Louis Johan Alexander Schoonheyt (1903-1986), commonly known as L. J. A. Schoonheyt, was a Dutch medical doctor, writer, and supporter of the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands before World War II. From 1935 to 1936 he was the camp doctor at the Boven-Digoel concentration camp in New Guinea, Dutch East Indies, and is mostly known today for the book he wrote about his experiences there, Boven-Digoel: Het land van communisten en kannibalen (1936). His praise for the conditions in the camp earned him the ire of the internees, Indonesian nationalists, and Dutch human rights advocates; E. du Perron called him a 'colonial bandit', while many internees burned his book after reading it in the camp.

Soekaesih was a Communist Party of Indonesia activist known for being one of only a handful of female political prisoners exiled by the Netherlands government to Boven-Digoel concentration camp. After being released she traveled to the Netherlands in the late 1930s and campaigned for the camp to be shut down.

Paul Alex Blaauw, usually known as P. A. Blaauw, was an Indo politician, lawyer, and member of the Dutch East Indies Volksraad representing the Indo Europeesch Verbond from the 1920s to the 1940s. During the period of transition to Indonesian independence and the 1949 Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference he was a leader of the largest faction advocating for the rights of Indos.

Censorship in the Dutch East Indies was significantly stricter than in the Netherlands, as the freedom of the press guaranteed in the Constitution of the Netherlands did not apply in the country's overseas colonies. Before the twentieth century, official censorship focused mainly on Dutch-language materials, aiming at protecting the trade and business interests of the colony and the reputation of colonial officials. In the early twentieth century, with the rise of Indonesian nationalism, censorship also encompassed materials printed in local languages such as Malay and Javanese, and enacted a repressive system of arrests, surveillance and deportations to combat anti-colonial sentiment.

The Nederlandsch-Indische Escompto Maatschappij was a significant Dutch bank, founded in 1857 in Batavia, Dutch East Indies. In the first half of the 20th century, it was the smallest of the “big three” commercial banks, behind the Netherlands Trading Society and the Nederlandsch-Indische Handelsbank, that dominated the Dutch East Indies’ financial system alongside the note-issuing Bank of Java.

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 "Indische Pers". Journalistiek in de Tropen (in Dutch). International Institute of Social History. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ Van der Veur 18.

- ↑ Maters 37-38.

- ↑ Ingleson 69.

- ↑ Maters 143–45.

- ↑ Maters 214.

- 1 2 Witte 17.

- ↑ Vogel 190.

- ↑ Vogel 193.

Bibliography

- Ingleson, John (2014). Workers, Unions and Politics: Indonesia in the 1920s and 1930s. Brill. ISBN 9789004264762.

- Maters, Mirjam (1998). Van zachte wenk tot harde hand: persvrijheid en persbreidel in Nederlands-Indië, 1906-1942 (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 9789065505965.

- Veur, Paul W. Van der (2006). The lion and the gadfly: Dutch colonialism and the spirit of E.F.E. Douwes Dekker. KITLV Press. ISBN 9789067182423.

- Vogel, Jaap (1992). De opkomst van het Indocentrische geschiedbeeld: leven en werken van B.J.O. Schrieke en J.C. van Leur (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 9789065504067.

- Witte, René (1998). De Indische radio-omroep: overheidsbeleid en ontwikkeling, 1923-1942 (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 9789065505903.