Acrylic paint is a fast-drying paint made of pigment suspended in acrylic polymer emulsion and plasticizers, silicone oils, defoamers, stabilizers, or metal soaps. Most acrylic paints are water-based, but become water-resistant when dry. Depending on how much the paint is diluted with water, or modified with acrylic gels, mediums, or pastes, the finished acrylic painting can resemble a watercolor, a gouache, or an oil painting, or it may have its own unique characteristics not attainable with other media.

Paul Jackson Pollock was an American painter. A major figure in the abstract expressionist movement, Pollock was widely noticed for his "drip technique" of pouring or splashing liquid household paint onto a horizontal surface, enabling him to view and paint his canvases from all angles. It was called all-over painting and action painting, since he covered the entire canvas and used the force of his whole body to paint, often in a frenetic dancing style. This extreme form of abstraction divided critics: some praised the immediacy of the creation, while others derided the random effects.

Oil painting is a painting method involving the procedure of painting with pigments with a medium of drying oil as the binder. It has been the most common technique for artistic painting on canvas, wood panel or copper for several centuries, spreading from Europe to the rest of the world. The advantages of oil for painting images include "greater flexibility, richer and denser color, the use of layers, and a wider range from light to dark". But the process is slower, especially when one layer of paint needs to be allowed to dry before another is applied.

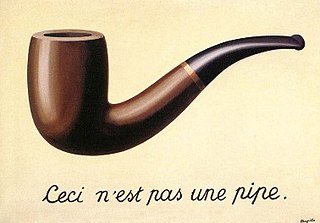

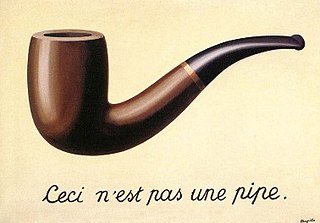

Surrealism is an art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike scenes and ideas. Its intention was, according to leader André Breton, to "resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality", or surreality. It produced works of painting, writing, theatre, filmmaking, photography, and other media as well.

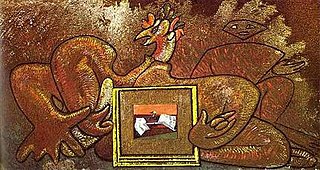

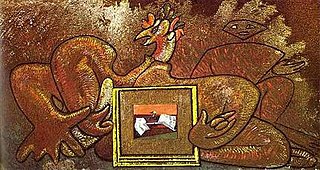

Max Ernst was a German painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and Surrealism in Europe. He had no formal artistic training, but his experimental attitude toward the making of art resulted in his invention of frottage—a technique that uses pencil rubbings of textured objects and relief surfaces to create images—and grattage, an analogous technique in which paint is scraped across canvas to reveal the imprints of the objects placed beneath. Ernst is noted for his unconventional drawing methods as well as for creating novels and pamphlets using the method of collages. He served as a soldier for four years during World War I, and this experience left him shocked, traumatised and critical of the modern world. During World War II he was designated an "undesirable foreigner" while living in France.

Surrealist automatism is a method of art-making in which the artist suppresses conscious control over the making process, allowing the unconscious mind to have great sway. This drawing technique was popularized in the early 1920s, by Andre Masson and Hans Arp.

Surrealism in art, poetry, and literature uses numerous techniques and games to provide inspiration. Many of these are said to free imagination by producing a creative process free of conscious control. The importance of the unconscious as a source of inspiration is central to the nature of surrealism.

Gouache, body color, or opaque watercolor is a water-medium paint consisting of natural pigment, water, a binding agent, and sometimes additional inert material. Gouache is designed to be opaque. Gouache has a long history, having been used for at least twelve centuries. It is used most consistently by commercial artists for posters, illustrations, comics, and other design work.

Fingerpaint is a kind of paint intended to be applied with the fingers; it typically comes in tubes and is used by small children, though it has occasionally been used by adults either to teach art to children, or for their own use.

A decal or transfer is a plastic, cloth, paper, or ceramic substrate that has printed on it a pattern or image that can be moved to another surface upon contact, usually with the aid of heat or water.

Jean-Paul Riopelle, was a Canadian painter and sculptor from Quebec. He had one of the longest and most important international careers of the sixteen signatories of the Refus Global, the 1948 manifesto that announced the Quebecois artistic community's refusal of clericalism and provincialism. He is best known for his abstract painting style, in particular his "mosaic" works of the 1950s when he famously abandoned the paintbrush, using only a palette knife to apply paint to canvas, giving his works a distinctive sculptural quality. He became the first Canadian painter since James Wilson Morrice to attain widespread international recognition and high praise, both during his career and after his death. He was a leading artist of French Lyrical Abstraction.

Loplop, or more formally, Loplop, Father Superior of the Birds, is the name of a birdlike character that was an alter ego of the Dada-Surrealist artist Max Ernst. Ernst had a ongoing fascination with birds, which often appear in his work. Loplop functioned as a familiar animal. William Rubin wrote of Ernst "Among his more successful works of the thirties are a series begun in 1930 around the theme of his alter ego, Loplop, Superior of the Birds." Loplop is an iconic image of surrealist art, the painting Loplop Introduces Loplop (1930) appears on the front cover of the Gaëtan Picon's book Surrealist and Surrealism 1919-1939, and the drawing and collage Loplop Presents (1932) was used as the frontispiece of Patrick Waldberg's book Surrealism.

The paranoiac-critical method is a surrealist technique developed by Salvador Dalí in the early 1930s. He employed it in the production of paintings and other artworks, especially those that involved optical illusions and other multiple images. The technique consists of the artist invoking a paranoid state. The result is a deconstruction of the psychological concept of identity, such that subjectivity becomes the primary aspect of the artwork.

Óscar M. Domínguez was a Spanish surrealist painter.

Valentine Hugo (1887–1968) was a French artist and writer. She was born Valentine Marie Augustine Gross, only daughter to Auguste Gross and Zélie Démelin, in Boulogne-sur-Mer. She is best known for her work with the Russian ballet and with the French Surrealists. Hugo died in Paris.

Sir Roland Algernon Penrose was an English artist, historian and poet. He was a major promoter and collector of modern art and an associate of the surrealists in the United Kingdom. During the Second World War he put his artistic skills to practical use as a teacher of camouflage.

Minotaure was a Surrealist-oriented magazine founded by Albert Skira and E. Tériade in Paris and published in French between 1933 and 1939. Minotaure published on the plastic arts, poetry, and literature, avant garde, as well as articles on esoteric and unusual aspects of literary and art history. Also included were psychoanalytical studies and artistic aspects of anthropology and ethnography. It was a lavish and extravagant magazine by the standards of the 1930s, profusely illustrated with high quality reproductions of art, often in color.

Underglaze is a method of decorating pottery in which painted decoration is applied to the surface before it is covered with a transparent ceramic glaze and fired in a kiln. Because the glaze subsequently covers it, such decoration is completely durable, and it also allows the production of pottery with a surface that has a uniform sheen. Underglaze decoration uses pigments derived from oxides which fuse with the glaze when the piece is fired in a kiln. It is also a cheaper method, as only a single firing is needed, whereas overglaze decoration requires a second firing at a lower temperature.

Painting is a visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface. The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and airbrushes, may be used. One who produces paintings is called a painter.

Judit Reigl was a Hungarian painter who lived in France.