South West Pacific Area (SWPA) was the name given to the Allied supreme military command in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands in the Pacific War. SWPA included the Philippines, Borneo, the Dutch East Indies, East Timor, Australia, the Territories of Papua and New Guinea, and the western part of the Solomon Islands. It primarily consisted of United States and Australian forces, although Dutch, Filipino, British, and other Allied forces also served in the SWPA.

The Women's Royal Australian Naval Service (WRANS) was the women's branch of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). In 1941, fourteen members of the civilian Women's Emergency Signalling Corps (WESC) were recruited for wireless telegraphy work at the Royal Australian Navy Wireless/Transmitting Station Canberra, as part of a trial to free up men for service aboard ships. Although the RAN and the Australian government were initially reluctant to support the idea, the demand for seagoing personnel imposed by the Pacific War saw the WRANS formally established as a women's auxiliary service in 1942. The surge in recruitment led to the development of an internal officer corps. Over the course of World War II, over 3,000 women served in the WRANS.

Australia entered World War II on 3 September 1939, following the government's acceptance of the United Kingdom's declaration of war on Nazi Germany. Australia later entered into a state of war with other members of the Axis powers, including the Kingdom of Italy on 11 June 1940, and the Empire of Japan on 9 December 1941. By the end of the war almost one million Australians had served in the armed forces, whose military units fought primarily in the European theatre, North African campaign, and the South West Pacific theatre. In addition, Australia came under direct attack for the first time in its post-colonial history. Its casualties from enemy action during the war were 27,073 killed and 23,477 wounded. Many more suffered from tropical disease, hunger, and harsh conditions in captivity; of the 21,467 Australian prisoners taken by the Japanese, only 14,000 survived.

Australia in the War of 1939–1945 is a 22-volume official history series covering Australian involvement in the Second World War. The series was published by the Australian War Memorial between 1952 and 1977, most of the volumes being edited by Gavin Long, who also wrote three volumes and the summary volume The Six Year War.

The 26th Brigade was an Australian Army infantry brigade of World War II. Formed in mid-1940, the brigade was assigned to the 7th Division initially, but later transferred to the 9th Division. It was primarily recruited from Victoria and South Australia. After training in Australia, in late 1940, the brigade deployed to the Middle East and subsequently took part in the siege of Tobruk, defending the vital port town between April and October 1941. After being relieved, the brigade undertook garrison duties in Syria in the first half of 1942, before taking part in the First and Second Battles of El Alamein between July and November 1942. After returning to Australia in early 1943, the brigade fought against the Japanese in New Guinea in 1943 and 1944, including the capture of Lae and the Huon Peninsula campaign, and then took part in the fighting on Tarakan in 1945. It was disbanded in early 1946.

Soldier settlement was the settlement of land throughout parts of Australia by returning discharged soldiers under soldier settlement schemes administered by state governments after World War I and World War II. The post-World War II settlements were co-ordinated by the Commonwealth Soldier Settlement Commission.

Although most Australian civilians lived far from the front line, the Australian home front during World War II played a significant role in the Allied victory and led to permanent changes to Australian society.

The 35th Battalion was an infantry battalion of the Australian Army. Originally raised in late 1915 for service during the First World War, the battalion saw service on the Western Front in France and Belgium before being disbanded in 1919. In 1921, it was re-raised in the Newcastle region of New South Wales as a unit of the Citizens Force. It was subsequently amalgamated a number of times during the inter-war years following the Great Depression, firstly with the 33rd Battalion and then the 2nd Battalion, before being re-raised in its own right upon the outbreak of the Second World War. Following this the battalion undertook garrison duties in Australia before being deployed to New Guinea where they took part in the Huon Peninsula campaign. After the end of the war, the 35th Battalion was disbanded in early 1946.

Clare Grant Stevenson, AM, MBE was the inaugural Director of the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF), from May 1941 to March 1946. As such, she was described in 2001 as "the most significant woman in the history of the Air Force". Formed as a branch of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) in March 1941, the WAAAF was the first and largest uniformed women's service in Australia during World War II, numbering more than 18,000 members by late 1944 and making up over thirty per cent of RAAF ground staff.

Air Vice-Marshal Joseph Eric Hewitt, was a senior commander in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). He joined the Royal Australian Navy in 1915, and transferred permanently to the Air Force in 1928. Hewitt commanded No. 101 Flight in the early 1930s, and No. 104 (Bomber) Squadron RAF on exchange in Britain shortly before World War II. He was appointed the RAAF's Assistant Chief of the Air Staff in 1941. The following year he was posted to Allied Air Forces Headquarters, South West Pacific Area, as Director of Intelligence. In 1943, he took command of No. 9 Operational Group, the RAAF's main mobile strike force, but was controversially sacked by the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Vice Marshal George Jones, less than a year later over alleged morale and disciplinary issues.

The Australian Army was the largest service in the Australian military during World War II. Prior to the outbreak of war the Australian Army was split into the small full-time Permanent Military Forces (PMF) and the larger part-time Militia. Following the outbreak of war on the 3rd of September 1939, 11 days later, on 14 September 1939 Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced that 40,000 members of the Militia would be called up for training and a 20,000-strong expeditionary force, designated the Second Australian Imperial Force, would be formed for overseas service. Meanwhile, conscription was introduced in October 1939 to keep the Militia at strength as its members volunteered for the AIF. The Australian Army subsequently made an important contribution to the Allied campaigns in the Mediterranean, the Middle East and North Africa fighting the Germans, Italians, and Vichy French during 1940 and 1941, and later in the jungles of the South West Pacific Area fighting the Japanese between late 1941 and 1945. Following the Japanese surrender Australian Army units were deployed as occupation forces across the South West Pacific. Meanwhile, the Army contributed troops to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) in Japan from 1946.

At the end of the Second World War, there were approximately five million servicemembers in the British Armed Forces. The demobilisation and reassimilation of this vast force back into civilian life was one of the first and greatest challenges facing the postwar British government.

The Royal Australian Army Dental Corps (RAADC) is a corps within the Australian Army. It was formed on 23 April 1943 during World War II as the Australian Army Dental Corps, before being granted the 'Royal' prefix in 1948. Prior to its formation dentists were part of the Australian Army Medical Corps. The role of the RAADC is to provide dental care to army personnel in order to minimise the requirement for the evacuation of dental casualties, to conserve manpower and to reduce the burden of casualty evacuation. In the post-war years, the corps has provided personnel to deployments in Japan, Korea and Vietnam. It has also contributed to peace-keeping operations in Somalia, Rwanda, Bougainville and East Timor.

The 27th Battalion was an infantry battalion of the Australian Army. It was initially raised in 1915 as part of the all-volunteer First Australian Imperial Force for service during World War I. During the conflict, the battalion saw action briefly at Gallipoli before later fighting on the Western Front between 1916 and 1918. It was disbanded in 1919, but was re-raised in 1921 as part of the Citizens Force, which later became the "Militia". During World War II the battalion was used mainly in a garrison role until the last year of the war when it was committed to the fighting against the Japanese during the Bougainville campaign. Following the end of hostilities it was disbanded in May 1946. Between 1948 and 1965 the battalion was re-raised and disbanded a number of times before eventually becoming part of the Royal South Australia Regiment. It was disbanded for a final time in 1987, when it was amalgamated with the 10th Battalion, Royal South Australia Regiment to form the 10th/27th Battalion, Royal South Australia Regiment.

The 37th/52nd Battalion was an infantry battalion of the Australian Army. Formed in 1930 from two previously existing Militia battalions, the battalion remained on the Australian order of battle until 1937. During World War II it was revived in 1942 and subsequently saw active service with the 4th Brigade against the Japanese in the Huon Peninsula and New Britain campaigns. It was disbanded after the war in 1946.

The 28th Battalion was an infantry battalion of the Australian Army. It was raised in early 1915 as part of the First Australian Imperial Force for service during the First World War and formed part of the 7th Brigade, attached to the 2nd Division. It fought during the final stages of the Gallipoli campaign in late 1915 and then on the Western Front between 1916 and 1918. At the end of the war, the 28th was disbanded in 1919 but was re-raised in 1921, as a part-time unit based in Western Australia. During the Second World War, the 28th undertook defensive duties in Australia for the majority of the conflict, before seeing action against the Japanese in the New Britain campaign in 1944–1945. The battalion was disbanded in March 1946 but was re-formed in 1948 as an amalgamated unit with the 16th Battalion, before being unlinked in 1952 and re-raised as a full battalion following the reintroduction of national service. It remained on the Australian Army's order of battle until 1960 when it was subsumed into the Royal Western Australia Regiment, but was later re-raised in 1966 as a remote area infantry battalion. In 1977, the 28th was reduced to an independent rifle company, and in 1987 was amalgamated into the 11th/28th Battalion, Royal Western Australia Regiment.

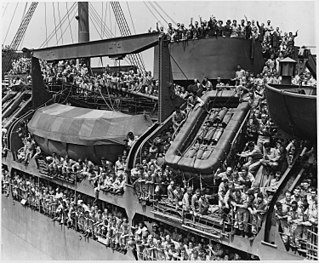

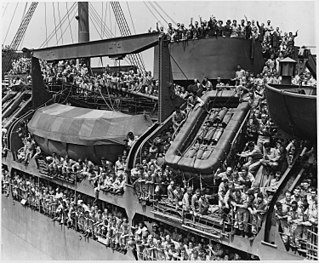

The Demobilization of United States armed forces after the Second World War began with the defeat of Germany in May 1945 and continued through 1946. The United States had more than 12 million men and women in the armed forces at the end of World War II, of whom 7.6 million were stationed abroad. The American public demanded a rapid demobilization and soldiers protested the slowness of the process. Military personnel were returned to the United States in Operation Magic Carpet. By June 30, 1947, the number of active duty soldiers, sailors, Marines, and airmen in the armed forces had been reduced to 1,566,000.

Operation Pamphlet, also called Convoy Pamphlet, was a World War II convoy operation conducted during January and February 1943 to transport the 9th Australian Division home from Egypt. The convoy involved five transports, which were protected from Japanese warships by several Allied naval task forces during the trip across the Indian Ocean and along the Australian coast. The division embarked in late January 1943 and the convoy operation began on 4 February. No contact was made between Allied and Japanese ships, and the division arrived in Australian ports during late February with no losses from enemy action.

Elements of the Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF) were located in the United Kingdom (UK) throughout World War II. For most of the war, these comprised only a small number of liaison officers. However, between June and December 1940 around 8,000 Australian soldiers organised into two infantry brigades and supporting units were stationed in the country. Several small engineer units were also sent to the UK, and up to 600 forestry troops were active there between July 1940 and mid-1943. A prisoner of war (POW) repatriation unit arrived in the UK in August 1944, and over 5,600 released AIF prisoners eventually passed through the country. Following the war, small numbers of Australian soldiers formed part of a military cricket team which toured England, and the Army contributed most members of the Australian contingent to the June 1946 victory parade in London.

Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme (CRTS) was an Australian government scheme started during World War II to offer vocational or academic training to both men and women who had served in the Australian Defence Force. Its purpose was to aid in the return of ex-service personnel to civilian employment. It operated from 1942 until last acceptances were taken in 1950. It was managed by the Department of Post-War Reconstruction.