In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term crime does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition, though statutory definitions have been provided for certain purposes. The most popular view is that crime is a category created by law; in other words, something is a crime if declared as such by the relevant and applicable law. One proposed definition is that a crime or offence is an act harmful not only to some individual but also to a community, society, or the state. Such acts are forbidden and punishable by law.

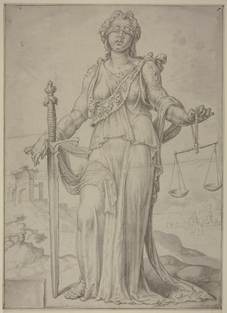

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspectives, including the concepts of moral correctness based on ethics, rationality, law, religion, equity and fairness.

Punishment, commonly, is the imposition of an undesirable or unpleasant outcome upon a group or individual, meted out by an authority—in contexts ranging from child discipline to criminal law—as a response and deterrent to a particular action or behavior that is deemed undesirable or unacceptable. It is, however, possible to distinguish between various different understandings of what punishment is.

Retributive justice is a theory of punishment that when an offender breaks the law, justice requires that they suffer in return, and that the response to a crime is proportional to the offence. As opposed to revenge, retribution—and thus retributive justice—is not personal, is directed only at wrongdoing, has inherent limits, involves no pleasure at the suffering of others, and employs procedural standards. Retributive justice contrasts with other purposes of punishment such as deterrence and rehabilitation of the offender.

The Youth Criminal Justice Act is a Canadian statute, which came into effect on April 1, 2003. It covers the prosecution of youths for criminal offences. The Act replaced the Young Offenders Act, which itself was a replacement for the Juvenile Delinquents Act.

In criminology, a political crime or political offence is an offence involving overt acts or omissions, which prejudice the interests of the state, its government, or the political system. It is to be distinguished from state crime, in which it is the states that break both their own criminal laws or public international law.

The term sentence in law refers to punishment that was actually ordered or could be ordered by a trial court in a criminal procedure. A sentence forms the final explicit act of a judge-ruled process as well as the symbolic principal act connected to their function. The sentence can generally involve a decree of imprisonment, a fine, and/or punishments against a defendant convicted of a crime. Those imprisoned for multiple crimes usually serve a concurrent sentence in which the period of imprisonment equals the length of the longest sentence where the sentences are all served together at the same time, while others serve a consecutive sentence in which the period of imprisonment equals the sum of all the sentences served sequentially, or one after the other. Additional sentences include intermediate, which allows an inmate to be free for about 8 hours a day for work purposes; determinate, which is fixed on a number of days, months, or years; and indeterminate or bifurcated, which mandates the minimum period be served in an institutional setting such as a prison followed by street time period of parole, supervised release or probation until the total sentence is completed.

Articles related to criminology and law enforcement.

Capital punishment is a legal punishment in India, permitted for some crimes under the country's main substantive penal legislation, the Indian Penal Code, as well as other laws. Executions are carried out by hanging.

Mandatory sentence requires that offenders serve a predefined term for certain crimes, commonly serious and violent offenses. Judges are bound by law; these sentences are produced through the legislature, not the judicial system. They are instituted to expedite the sentencing process and limit the possibility of irregularity of outcomes due to judicial discretion. Mandatory sentences are typically given to people who are convicted of certain serious and/or violent crimes, and require a prison sentence. Mandatory sentencing laws vary across nations; they are more prevalent in common law jurisdictions because civil law jurisdictions usually prescribe minimum and maximum sentences for every type of crime in explicit laws.

The Italian school of criminology was founded at the end of the 19th century by Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909) and two of his Italian disciples, Enrico Ferri (1856–1929) and Raffaele Garofalo (1851–1934).

The Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 (c.53) of the UK Parliament enables some criminal convictions to be ignored after a rehabilitation period. Its purpose is that people do not have a lifelong blot on their records because of a relatively minor offence in their past. The rehabilitation period is automatically determined by the sentence. After this period, if there has been no further conviction the conviction is "spent" and, with certain exceptions, need not be disclosed by the ex-offender in any context such as when applying for a job, obtaining insurance, or in civil proceedings. A conviction for the purposes of the ROA includes a conviction issued outside Great Britain and therefore foreign convictions are eligible to receive the protection of the ROA.

A discharge is a type of sentence imposed by a court whereby no punishment is imposed.

Right realism, in criminology, also known as New Right Realism, Neo-Classicism, Neo-Positivism, or Neo-Conservatism, is the ideological polar opposite of left realism. It considers the phenomenon of crime from the perspective of political conservatism and asserts that it takes a more realistic view of the causes of crime and deviance, and identifies the best mechanisms for its control. Unlike the other Schools of criminology, there is less emphasis on developing theories of causality in relation to crime and deviance. The school employs a rationalist, direct and scientific approach to policy-making for the prevention and control of crime. Some politicians who ascribe to the perspective may address aspects of crime policy in ideological terms by referring to freedom, justice, and responsibility. For example, they may be asserting that individual freedom should only be limited by a duty not to use force against others. This, however, does not reflect the genuine quality in the theoretical and academic work and the real contribution made to the nature of criminal behaviour by criminologists of the school.

In criminology, public-order crime is defined by Siegel (2004) as "crime which involves acts that interfere with the operations of society and the ability of people to function efficiently", i.e., it is behaviour that has been labelled criminal because it is contrary to shared norms, social values, and customs. Robertson (1989:123) maintains a crime is nothing more than "an act that contravenes a law". Generally speaking, deviancy is criminalized when it is too disruptive and has proved uncontrollable through informal sanctions.

In criminology, the classical school usually refers to the 18th-century work during the Enlightenment by the utilitarian and social-contract philosophers Jeremy Bentham and Cesare Beccaria. Their interests lay in the system of criminal justice and penology and indirectly, through the proposition that "man is a calculating animal", in the causes of criminal behavior. The classical school of thought was premised on the idea that people have free will in making decisions, and that punishment can be a deterrent for crime, so long as the punishment is proportional, fits the crime, and is carried out promptly.

Deterrence in relation to criminal offending is the idea or theory that the threat of punishment will deter people from committing crime and reduce the probability and/or level of offending in society. It is one of five objectives that punishment is thought to achieve; the other four objectives are denunciation, incapacitation, retribution and rehabilitation.

The sociology of punishment seeks to understand why and how we punish; the general justifying aim of punishment and the principle of distribution. Punishment involves the intentional infliction of pain and/or the deprivation of rights and liberties. Sociologists of punishment usually examine state-sanctioned acts in relation to law-breaking; why, for instance, citizens give consent to the legitimation of acts of violence.

Canadian criminal law is governed by the Criminal Code, which includes the principles and powers in relation to criminal sentencing in Canada.

Daṇḍa is the Hindu term for punishment. In ancient India, punishments were generally sanctioned by the ruler, but other legal officials could also play a part. The punishments that were handed out were in response to criminal activity. In the Hindu law tradition, there is a counterpart to daṇḍa which is prāyaścitta, or atonement. Where as daṇḍa is sanctioned primarily by the king, prāyaścitta is taken up by a person upon his or her own volition. Furthermore, daṇḍa provides a way for an offender to right any violations of dharma that he or she may have committed. In essence, daṇḍa functions as the ruler's tool to protect the system of life stages and castes. Daṇḍa makes up a part of vyavahāra, or legal procedure, which was also a responsibility afforded to the king.