An emulsion is a mixture of two or more liquids that are normally immiscible owing to liquid-liquid phase separation. Emulsions are part of a more general class of two-phase systems of matter called colloids. Although the terms colloid and emulsion are sometimes used interchangeably, emulsion should be used when both phases, dispersed and continuous, are liquids. In an emulsion, one liquid is dispersed in the other. Examples of emulsions include vinaigrettes, homogenized milk, liquid biomolecular condensates, and some cutting fluids for metal working.

Surface tension is the tendency of liquid surfaces at rest to shrink into the minimum surface area possible. Surface tension is what allows objects with a higher density than water such as razor blades and insects to float on a water surface without becoming even partly submerged.

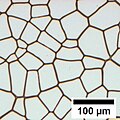

Soap films are thin layers of liquid surrounded by air. For example, if two soap bubbles come into contact, they merge and a thin film is created in between. Thus, foams are composed of a network of films connected by Plateau borders. Soap films can be used as model systems for minimal surfaces, which are widely used in mathematics.

In surface science, surface energy quantifies the disruption of intermolecular bonds that occurs when a surface is created. In solid-state physics, surfaces must be intrinsically less energetically favorable than the bulk of the material, otherwise there would be a driving force for surfaces to be created, removing the bulk of the material by sublimation. The surface energy may therefore be defined as the excess energy at the surface of a material compared to the bulk, or it is the work required to build an area of a particular surface. Another way to view the surface energy is to relate it to the work required to cut a bulk sample, creating two surfaces. There is "excess energy" as a result of the now-incomplete, unrealized bonding between the two created surfaces.

Electrowetting is the modification of the wetting properties of a surface with an applied electric field.

An artificial membrane, or synthetic membrane, is a synthetically created membrane which is usually intended for separation purposes in laboratory or in industry. Synthetic membranes have been successfully used for small and large-scale industrial processes since the middle of the twentieth century. A wide variety of synthetic membranes is known. They can be produced from organic materials such as polymers and liquids, as well as inorganic materials. Most commercially utilized synthetic membranes in industry are made of polymeric structures. They can be classified based on their surface chemistry, bulk structure, morphology, and production method. The chemical and physical properties of synthetic membranes and separated particles as well as separation driving force define a particular membrane separation process. The most commonly used driving forces of a membrane process in industry are pressure and concentration gradient. The respective membrane process is therefore known as filtration. Synthetic membranes utilized in a separation process can be of different geometry and flow configurations. They can also be categorized based on their application and separation regime. The best known synthetic membrane separation processes include water purification, reverse osmosis, dehydrogenation of natural gas, removal of cell particles by microfiltration and ultrafiltration, removal of microorganisms from dairy products, and dialysis.

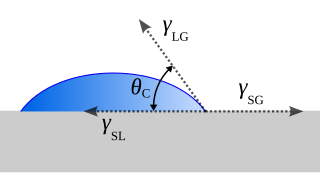

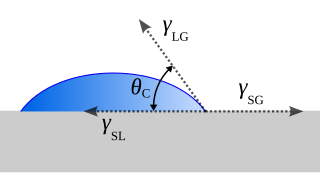

Wetting is the ability of a liquid to displace gas to maintain contact with a solid surface, resulting from intermolecular interactions when the two are brought together. This happens in presence of a gaseous phase or another liquid phase not miscible with the first one. The degree of wetting (wettability) is determined by a force balance between adhesive and cohesive forces. There are two types of wetting: non-reactive wetting and reactive wetting.

The Marangoni effect is the mass transfer along an interface between two phases due to a gradient of the surface tension. In the case of temperature dependence, this phenomenon may be called thermo-capillary convection.

The contact angle is the angle between a liquid surface and a solid surface where they meet. More specifically, it is the angle between the surface tangent on the liquid–vapor interface and the tangent on the solid–liquid interface at their intersection. It quantifies the wettability of a solid surface by a liquid via the Young equation.

A Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) film is an emerging kind of 2D materials to fabricate heterostructures for nanotechnology, formed when Langmuir films—or Langmuir monolayers (LM)—are transferred from the liquid-gas interface to solid supports during the vertical passage of the support through the monolayers. LB films can contain one or more monolayers of an organic material, deposited from the surface of a liquid onto a solid by immersing the solid substrate into the liquid. A monolayer is adsorbed homogeneously with each immersion or emersion step, thus films with very accurate thickness can be formed. This thickness is accurate because the thickness of each monolayer is known and can therefore be added to find the total thickness of a Langmuir–Blodgett film.

Microemulsions are clear, thermodynamically stable, isotropic liquid mixtures of oil, water and surfactant, frequently in combination with a cosurfactant. The aqueous phase may contain salt(s) and/or other ingredients, and the "oil" may actually be a complex mixture of different hydrocarbons. In contrast to ordinary emulsions, microemulsions form upon simple mixing of the components and do not require the high shear conditions generally used in the formation of ordinary emulsions. The three basic types of microemulsions are direct, reversed and bicontinuous.

In chemistry and materials science, ultrahydrophobic surfaces are highly hydrophobic, i.e., extremely difficult to wet. The contact angles of a water droplet on an ultrahydrophobic material exceed 150°. This is also referred to as the lotus effect, after the superhydrophobic leaves of the lotus plant. A droplet striking these kinds of surfaces can fully rebound like an elastic ball. Interactions of bouncing drops can be further reduced using special superhydrophobic surfaces that promote symmetry breaking, pancake bouncing or waterbowl bouncing.

In physics, a "coffee ring" is a pattern left by a puddle of particle-laden liquid after it evaporates. The phenomenon is named for the characteristic ring-like deposit along the perimeter of a spill of coffee. It is also commonly seen after spilling red wine. The mechanism behind the formation of these and similar rings is known as the coffee ring effect or in some instances, the coffee stain effect, or simply ring stain.

The vapor–liquid–solid method (VLS) is a mechanism for the growth of one-dimensional structures, such as nanowires, from chemical vapor deposition. The growth of a crystal through direct adsorption of a gas phase on to a solid surface is generally very slow. The VLS mechanism circumvents this by introducing a catalytic liquid alloy phase which can rapidly adsorb a vapor to supersaturation levels, and from which crystal growth can subsequently occur from nucleated seeds at the liquid–solid interface. The physical characteristics of nanowires grown in this manner depend, in a controllable way, upon the size and physical properties of the liquid alloy.

Paint has four major components: pigments, binders, solvents, and additives. Pigments serve to give paint its color, texture, toughness, as well as determining if a paint is opaque or not. Common white pigments include titanium dioxide and zinc oxide. Binders are the film forming component of a paint as it dries and affects the durability, gloss, and flexibility of the coating. Polyurethanes, polyesters, and acrylics are all examples of common binders. The solvent is the medium in which all other components of the paint are dissolved and evaporates away as the paint dries and cures. The solvent also modifies the curing rate and viscosity of the paint in its liquid state. There are two types of paint: solvent-borne and water-borne paints. Solvent-borne paints use organic solvents as the primary vehicle carrying the solid components in a paint formulation, whereas water-borne paints use water as the continuous medium. The additives that are incorporated into paints are a wide range of things which impart important effects on the properties of the paint and the final coating. Common paint additives are catalysts, thickeners, stabilizers, emulsifiers, texturizers, biocides to fight bacterial growth, etc.

Adsorption is the adhesion of ions or molecules onto the surface of another phase. Adsorption may occur via physisorption and chemisorption. Ions and molecules can adsorb to many types of surfaces including polymer surfaces. A polymer is a large molecule composed of repeating subunits bound together by covalent bonds. In dilute solution, polymers form globule structures. When a polymer adsorbs to a surface that it interacts favorably with, the globule is essentially squashed, and the polymer has a pancake structure.

Polymeric materials have widespread application due to their versatile characteristics, cost-effectiveness, and highly tailored production. The science of polymer synthesis allows for excellent control over the properties of a bulk polymer sample. However, surface interactions of polymer substrates are an essential area of study in biotechnology, nanotechnology, and in all forms of coating applications. In these cases, the surface characteristics of the polymer and material, and the resulting forces between them largely determine its utility and reliability. In biomedical applications for example, the bodily response to foreign material, and thus biocompatibility, is governed by surface interactions. In addition, surface science is integral part of the formulation, manufacturing, and application of coatings.

Elasto-capillarity is the ability of capillary force to deform an elastic material. From the viewpoint of mechanics, elastocapillarity phenomena essentially involve competition between the elastic strain energy in the bulk and the energy on the surfaces/interfaces. In the modeling of these phenomena, some challenging issues are, among others, the exact characterization of energies at the micro scale, the solution of strongly nonlinear problems of structures with large deformation and moving boundary conditions, and instability of either solid structures or droplets/films.The capillary forces are generally negligible in the analysis of macroscopic structures but often play a significant role in many phenomena at small scales.

Self-cleaning surfaces are a class of materials with the inherent ability to remove any debris or bacteria from their surfaces in a variety of ways. The self-cleaning functionality of these surfaces are commonly inspired by natural phenomena observed in lotus leaves, gecko feet, and water striders to name a few. The majority of self-cleaning surfaces can be placed into three categories:

- superhydrophobic

- superhydrophilic

- photocatalytic.

Wetting solutions are liquids containing active chemical compounds that minimise the distance between two immiscible phases by lowering the surface tension to induce optimal spreading. The two phases, known as an interface, can be classified into five categories, namely, solid-solid, solid-liquid, solid-gas, liquid-liquid and liquid-gas.