Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival style of architecture. His work culminated in designing the interior of the Palace of Westminster in Westminster, London, and its renowned clock tower, the Elizabeth Tower, which houses the bell known as Big Ben. Pugin designed many churches in England, and some in Ireland and Australia. He was the son of Auguste Pugin, and the father of Edward Welby Pugin, Cuthbert Welby Pugin, and Peter Paul Pugin, who continued his architectural and interior design firm as Pugin & Pugin.

Gothic Revival is an architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half of the 19th century, mostly in England. Increasingly serious and learned admirers sought to revive medieval Gothic architecture, intending to complement or even supersede the neoclassical styles prevalent at the time. Gothic Revival draws upon features of medieval examples, including decorative patterns, finials, lancet windows, and hood moulds. By the middle of the 19th century, Gothic Revival had become the pre-eminent architectural style in the Western world, only to begin to fall out of fashion in the 1880s and early 1890s.

Victorian architecture is a series of architectural revival styles in the mid-to-late 19th century. Victorian refers to the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901), called the Victorian era, during which period the styles known as Victorian were used in construction. However, many elements of what is typically termed "Victorian" architecture did not become popular until later in Victoria's reign, roughly from 1850 and later. The styles often included interpretations and eclectic revivals of historic styles (see Historicism). The name represents the British and French custom of naming architectural styles for a reigning monarch. Within this naming and classification scheme, it followed Georgian architecture and later Regency architecture and was succeeded by Edwardian architecture.

The architecture of England is the architecture of modern England and in the historic Kingdom of England. It often includes buildings created under English influence or by English architects in other parts of the world, particularly in the English and later British colonies and Empire, which developed into the Commonwealth of Nations.

William Wilkinson Wardell (1823–1899) was a civil engineer and architect, notable not only for his work in Australia, the country to which he emigrated in 1858, but for a successful career as a surveyor and ecclesiastical architect in England and Scotland before his departure.

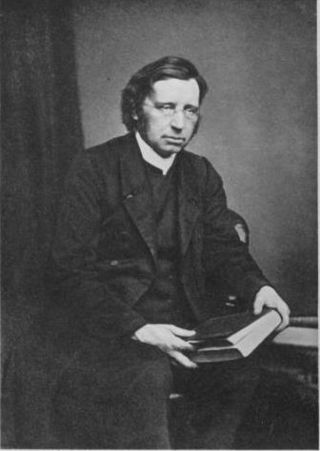

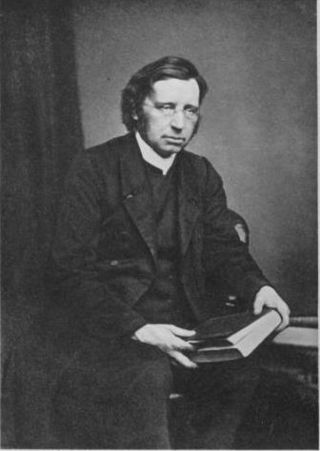

Richard Cromwell Carpenter was an English architect. He is chiefly remembered as an ecclesiastical and tractarian architect working in the Gothic style.

Romanesque Revival is a style of building employed beginning in the mid-19th century inspired by the 11th- and 12th-century Romanesque architecture. Unlike the historic Romanesque style, Romanesque Revival buildings tended to feature more simplified arches and windows than their historic counterparts.

The Cambridge Camden Society, known from 1845 as the Ecclesiological Society, was a learned society founded in 1839 to promote "the study of Gothic Architecture, and of Ecclesiastical Antiques". Its activities came to include publishing a monthly journal, The Ecclesiologist, advising church builders on their blueprints, and advocating a return to a medieval style of church architecture in England, known as Gothic Revival Architecture. At its peak influence in the 1840s, the society had over 700 members, including bishops of the Church of England, deans at the University of Cambridge, and Members of Parliament. The society and its publications enjoyed wide influence over the design of English churches throughout the 19th century, and are often known as the ecclesiological movement.

Abney Park Chapel, is a Grade II Listed chapel, designed by William Hosking and built by John Jay that is situated in Europe's first wholly nondenominational cemetery, Abney Park Cemetery, London.

Benjamin Woolfield Mountfort was an English emigrant to New Zealand, where he became one of the country's most prominent 19th-century architects. He was instrumental in shaping the city of Christchurch's unique architectural identity and culture, and was appointed the first official Provincial Architect of the developing province of Canterbury. Heavily influenced by the Anglo-Catholic philosophy behind early Victorian architecture, he is credited with importing the Gothic revival style to New Zealand. His Gothic designs constructed in both wood and stone in the province are considered unique to New Zealand. Today, he is considered the founding architect of the province of Canterbury.

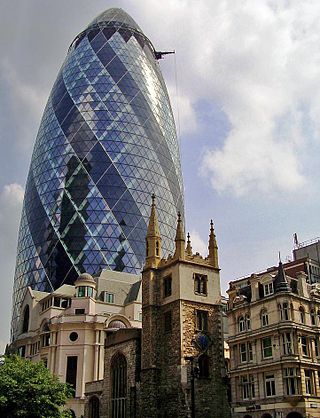

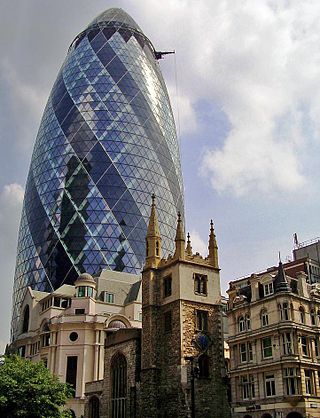

London's architectural heritage consists of buildings from a wide variety of styles and historical periods. London's distinctive architectural eclecticism stems from its long history, continual redevelopment, destruction by the Great Fire of London and The Blitz, and state recognition of private property rights which have limited large-scale state planning. This sets London apart from other European capitals such as Paris and Rome which are more architecturally homogeneous. London's diverse architecture ranges from the Romanesque central keep of The Tower of London, the great Gothic church of Westminster Abbey, the Palladian royal residence Queen's House, Christopher Wren's Baroque masterpiece St Paul's Cathedral, the High Victorian Gothic of The Palace of Westminster, the industrial Art Deco of Battersea Power Station, the post-war Modernism of The Barbican Estate and the Postmodern skyscraper 30 St Mary Axe 'The Gherkin'.

John Louis Petit was an artist and architectural historian whose paintings of buildings and landscapes, almost exclusively in watercolour, complemented his activities as one of the mid-19th century's leading writers and speakers on ecclesiastical architecture. He was a vocal opponent of the dominant architectural orthodoxies of the Gothic Revival.

A revival of the art and craft of stained-glass window manufacture took place in early 19th-century Britain, beginning with an armorial window created by Thomas Willement in 1811–12. The revival led to stained-glass windows becoming such a common and popular form of coloured pictorial representation that many thousands of people, most of whom would never commission or purchase a painting, contributed to the commission and purchase of stained-glass windows for their parish church.

Gothic Revival architecture in Canada is an historically influential style, with many prominent examples. The Gothic Revival style was imported to Canada from Britain and the United States in the early 19th century, and it rose to become the most popular style for major projects throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Rev. Frederick James Jobson D.D. - commonly styled F. J. Jobson - painter, architect and Wesleyan Methodist minister, became President of the Methodist Conference in 1869, and Treasurer of the Wesleyan Methodist Foreign Mission Society, 1869–1882. Alongside his important role in encouraging Methodist architecture, he was the author of devotional, architectural, biographical and travel books - which, combined with his role superintending the Wesleyan Methodist Magazine for over a decade and related duties - led to a great expansion of Methodist publishing. His topographical paintings provide a further legacy.

The Seven Lamps of Architecture is an extended essay, first published in May 1849 and written by the English art critic and theorist John Ruskin. The 'lamps' of the title are Ruskin's principles of architecture, which he later enlarged upon in the three-volume The Stones of Venice. To an extent, they codified some of the contemporary thinking behind the Gothic Revival. At the time of its publication, A. W. N. Pugin and others had already advanced the ideas of the Revival and it was well under way in practice. Ruskin offered little new to the debate, but the book helped to capture and summarise the thoughts of the movement. The Seven Lamps also proved a great popular success, and received the approval of the ecclesiologists typified by the Cambridge Camden Society, who criticised in their publication The Ecclesiologist lapses committed by modern architects in ecclesiastical commissions.

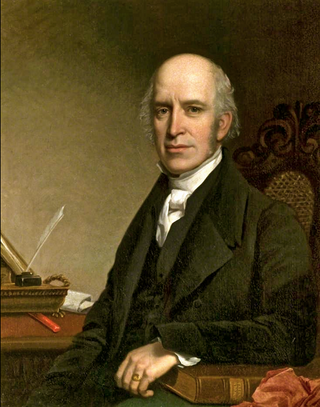

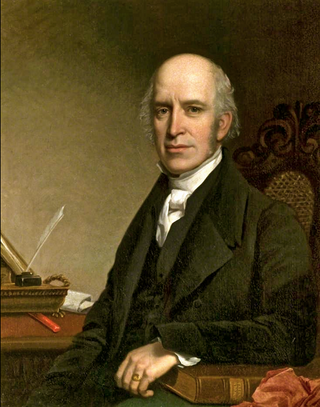

Edward James Willson was an English architect, antiquary, architectural writer, and mayor of Lincoln in 1851–2.

Church architecture of England refers to the architecture of buildings of Christian churches in England. It has evolved over the two thousand years of the Christian religion, partly by innovation and partly by imitating other architectural styles as well as responding to changing beliefs, practices and local traditions. Christian architecture encompasses a wide range of both secular and religious styles from the foundation of Christianity to the present day, influencing the design and construction of buildings and structures in Christian culture. From the birth of Christianity to the present, the most significant period of transformation for Christian architecture and design was the Gothic cathedral.

Romanesque Revival, Norman Revival or Neo-Norman styles of building in the United Kingdom were inspired by the Romanesque architecture of the 11th and 12th centuries AD.

Michael O'Connor was an Irish stained-glass artist based successively in Dublin, Bristol and London. A pupil of Thomas Willement, he developed a Gothic Revival style under the influence of Augustus Pugin, with whom he worked. He acquired a high reputation, and was commissioned to create windows for several cathedrals in England, Wales and Ireland. He is now seen as one of the leading stained-glass artists of his generation working in Britain. His stained-glass firm survived his death, initially under the management of his sons, and lasted until 1915.