Related Research Articles

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was a United States federal law of the New Deal era designed to boost agricultural prices by reducing surpluses. The government bought livestock for slaughter and paid farmers subsidies not to plant on part of their land. The money for these subsidies was generated through an exclusive tax on companies that processed farm products. The Act created a new agency, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, also called "AAA" (1933–1942), an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, to oversee the distribution of the subsidies. The Agriculture Marketing Act, which established the Federal Farm Board in 1929, was seen as an important precursor to this act. The AAA, along with other New Deal programs, represented the federal government's first substantial effort to address economic welfare in the United States.

An agricultural subsidy is a government incentive paid to agribusinesses, agricultural organizations and farms to supplement their income, manage the supply of agricultural commodities, and influence the cost and supply of such commodities.

The causes of the Great Depression in the early 20th century in the United States have been extensively discussed by economists and remain a matter of active debate. They are part of the larger debate about economic crises and recessions. The specific economic events that took place during the Great Depression are well established.

The Farm Service Agency (FSA) is the United States Department of Agriculture agency that was formed by merging the farm loan portfolio and staff of the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) and the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS). The Farm Service Agency implements agricultural policy, administers credit and loan programs, and manages conservation, commodity, disaster, and farm marketing programs through a national network of offices. The Administrator of FSA reports to the Under Secretary of Agriculture for Farm Production and Conservation. The current administrator is Zach Ducheneaux. The FSA of each state is led by a politically appointed State Executive Director (SED).

The history of agriculture in the United States covers the period from the first English settlers to the present day. In Colonial America, agriculture was the primary livelihood for 90% of the population, and most towns were shipping points for the export of agricultural products. Most farms were geared toward subsistence production for family use. The rapid growth of population and the expansion of the frontier opened up large numbers of new farms, and clearing the land was a major preoccupation of farmers. After 1800, cotton became the chief crop in southern plantations, and the chief American export. After 1840, industrialization and urbanization opened up lucrative domestic markets. The number of farms grew from 1.4 million in 1850, to 4.0 million in 1880, and 6.4 million in 1910; then started to fall, dropping to 5.6 million in 1950 and 2.2 million in 2008.

The Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act is a 1946 United States federal law that created the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) to provide low-cost or free school lunch meals to qualified students through subsidies to schools. The program was established as a way to prop up food prices by absorbing farm surpluses, while at the same time providing food to school-age children. It was named after Richard Russell Jr., signed into law by President Harry S. Truman in 1946, and entered the federal government into schools' dietary programs on June 4, 1946.

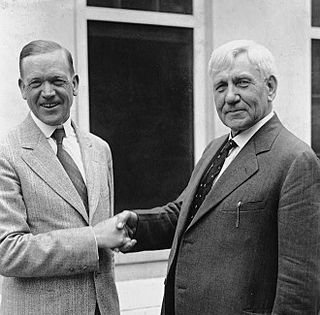

The McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Act, which never became law, was a controversial plan in the 1920s to subsidize American agriculture by raising the domestic prices of five crops. The plan was for the government to buy each crop and then store it or export it at a loss. It was co-authored by Charles L. McNary (R-Oregon) and Gilbert N. Haugen (R-Iowa). Despite attempts in 1924, 1926, 1927, and 1931 to pass the bill, it was vetoed by President Calvin Coolidge, and not approved. It was supported by Secretary of Agriculture Henry Cantwell Wallace and Vice President Charles Dawes.

A smallholding or smallholder is a small farm operating under a small-scale agriculture model. Definitions vary widely for what constitutes a smallholder or small-scale farm, including factors such as size, food production technique or technology, involvement of family in labor and economic impact. There are an estimated 500 million smallholder farms in developing countries of the world alone, supporting almost two billion people. Smallholdings are usually farms supporting a single family with a mixture of cash crops and subsistence farming. As a country becomes more affluent, smallholdings may not be self-sufficient, but may be valued for providing supplemental sustenance, recreation, and general rural lifestyle appreciation. As the sustainable food and local food movements grow in affluent countries, some of these smallholdings are gaining increased economic viability in the developed world as well.

Gilbert Nelson Haugen was a seventeen-term Republican U.S. Representative from Iowa's 4th congressional district, then located in northeastern Iowa. For nearly five years, he was the longest-serving member of the House. Born before the American Civil War, and first elected to Congress in the 19th century, Haugen served until his defeat in the 1932 Franklin D. Roosevelt landslide.

In the United States, the farm bill is comprehensive omnibus bill that is the primary agricultural and food policy instrument of the federal government. Congress typically passes a new farm bill every five to six years.

George Nelson Peek was an American agricultural economist, business executive, and civil servant. He was the first administrator of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) and the first president of the two banks that would become the Export-Import Bank of the United States.

Herbert Hoover's tenure as the 31st president of the United States began on his inauguration on March 4, 1929, and ended on March 4, 1933. Hoover, a Republican, took office after a landslide victory in the 1928 presidential election over Democrat Al Smith of New York. His presidency ended following his defeat in the 1932 presidential election by Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The agricultural policy of the United States is composed primarily of the periodically renewed federal U.S. farm bills. The Farm Bills have a rich history which initially sought to provide income and price support to US farmers and prevent them from adverse global as well as local supply and demand shocks. This implied an elaborate subsidy program which supports domestic production by either direct payments or through price support measures. The former incentivizes farmers to grow certain crops which are eligible for such payments through environmentally conscientious practices of farming. The latter protects farmers from vagaries of price fluctuations by ensuring a minimum price and fulfilling their shortfalls in revenue upon a fall in price. Lately, there are other measures through which the government encourages crop insurance and pays part of the premium for such insurance against various unanticipated outcomes in agriculture.

The Great Depression in India was a period of economic depression in the Indian subcontinent, then under British colonial rule. Beginning in 1929 in the United States, the Great Depression soon began to spread to countries around the globe. A global financial crisis, combined with protectionist policies adopted by the colonial government resulted in a rapid increase in the price of commodities in British India. During the period 1929–1937, exports and imports in India fell drastically, crippling seaborne international trade in the region; the Indian railway and agricultural sectors were the most affected by the depression. Discontent from farmers resulted in riots and rebellions against colonial rule, while increasing Indian nationalism led to the Salt Satyagraha of 1930, in which Mahatma Gandhi undertook marches to the sea in order to protest against the British salt tax.

A farm crisis describes times of agricultural recession, low crop prices and low farm incomes. The most recent US farm crisis occurred during the 1980s.

The latter part of the 19th century was a period of agrarian unrest in the Midwestern United States. From 1865 to 1896, farmer protests led to the formation of organized movements including the Grange, the Populist Party, the Greenbacks, and other alliances. Farmers cited the reasons for their unhappiness as declining prices, decreasing purchasing power, and monopolistic practices of: 1) moneylenders, 2) railroad corporations, and 3) other middlemen. Recent research has led scholars to question the validity of these explanations. Currently there is no scholarly consensus on the causes of agrarian discontent.

The Agricultural Act of 1948 was enacted by the United States Congress and signed into law by President Harry S. Truman on July 3, 1948. The legislation revised and authorized several aspects of U.S. agricultural policy and agricultural subsidies.

Wheat is produced in almost every state in the United States, and is one of the most grown grains in the country. The type and quantity vary between regions. The US is ranked fourth in production volume of wheat, with almost 50 million tons produced in 2020, behind only China, India and Russia. The US is ranked first in crop export volume; almost 50% of its total wheat production is exported.

The Brannan Plan was a failed United States farm bill from 1949. It called for "compensatory payments" to American farmers in response to the major problem of large agricultural surpluses stemming from price supports for farmers. The Brannan Plan was named after Charles Brannan, who served as the fourteenth United States Secretary of Agriculture from 1948 to 1953 as a liberal member of President Harry S. Truman's cabinet. It was blocked by conservatives and never became law. The start of the Korean War in June 1950 made the surpluses a vital weapon and prices soared as surpluses were used up, making the proposal irrelevant.

Milburn Lincoln Wilson was an American Undersecretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman under the New Deal and Fair Deal. His main interest was social justice for farmers. He made major contributions to federal agricultural policies, including creating the first domestic allotment plan for the Agricultural Adjustment Act and helping to create the first agricultural commodity programs and for the United States. He also convinced the Millers' National Federation and others to begin enriching bread and cereals.

References

- ↑ Boulding, K.E. (August 1947). "Economic Analysis and Agricultural Policy". Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science. 3. 13 (3): 439–440. doi:10.2307/137769. JSTOR 137769.

- ↑ Libecap, Gary D. (1998). "6". In Michael Bordo; Claudia Goldin; Eugene White (eds.). The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century (PDF). University of Chicago Press. p. 185.

- ↑ Libecap, pg. 190

- ↑ Libecap, pg. 211

- ↑ Bean, L.H.; P.H. Bollinger (Feb 1939). "The Base Period for Parity Prices". Journal of Farm Economics. 21 (1): 253. doi:10.2307/1230643. JSTOR 1230643.

- ↑ Libecap, pg. 185

- ↑ Libecap, pg.186

- ↑ Libecap, pg.188

- ↑ Elizabeth Hoffman & Gary Libecap (1994). "6". In Claudia Goldin & Gary Libecap (eds.). The Regulated Economy: A Historical Approach to Political Economy (PDF). University of Chicago Press. p. 189.

- ↑ Fausold, Martin (April 1977). "President Hoover's Farm Policies 1929-1933". Agricultural History. 51 (2): 372. JSTOR 3741165.

- ↑ Libecap, pg. 190

- ↑ Hoffman and Libecap, pg. 191

- ↑ Bean and Bollinger, pg. 254

- ↑ Libecap, pg. 197

- ↑ Bowers, Douglas; Wayne Rasmussen; Gladys Baker (Dec 1984). "History of Agricultural Price-Support and Adjustment Programs, 1933-84". Agriculture Information Bulletin (485): 18. Archived from the original on 2010-10-15. Retrieved 2011-03-01.

- ↑ Bean and Bollinger, pg. 253-254

- ↑ Boulding, pg. 439