Related Research Articles

In poetry, a hendecasyllable is a line of eleven syllables. The term may refer to several different poetic meters, the older of which are quantitative and used chiefly in classical poetry, and the newer of which are syllabic or accentual-syllabic and used in medieval and modern poetry.

In poetry, metre or meter is the basic rhythmic structure of a verse or lines in verse. Many traditional verse forms prescribe a specific verse metre, or a certain set of metres alternating in a particular order. The study and the actual use of metres and forms of versification are both known as prosody.

Poetry is a form of literary art that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, literal or surface-level meanings. Any particular instance of poetry is called a poem and is written by a poet. Poets use a variety of techniques called poetic devices, such as assonance, alliteration, euphony and cacophony, onomatopoeia, rhythm, and sound symbolism, to produce musical or other artistic effects. Most written poems are formatted in verse: a series or stack of lines on a page, which follow a rhythmic or other deliberate structure. For this reason, verse has also become a synonym for poetry.

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds in the final stressed syllables and any following syllables of two or more words. Most often, this kind of rhyming is consciously used for a musical or aesthetic effect in the final position of lines within poems or songs. More broadly, a rhyme may also variously refer to other types of similar sounds near the ends of two or more words. Furthermore, the word rhyme has come to be sometimes used as a shorthand term for any brief poem, such as a nursery rhyme or Balliol rhyme.

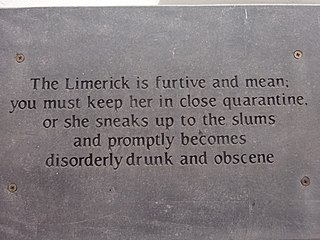

A limerick is a form of verse that appeared in Limerick, County Limerick, Ireland in the early years of the 18th century. In combination with a refrain, it forms a limerick song, a traditional humorous drinking song often with obscene verses. It is written in five-line, predominantly anapestic and amphibrach trimeter with a strict rhyme scheme of AABBA, in which the first, second and fifth line rhyme, while the third and fourth lines are shorter and share a different rhyme.

Poetry analysis is the process of investigating the form of a poem, content, structural semiotics, and history in an informed way, with the aim of heightening one's own and others' understanding and appreciation of the work.

The Sapphic stanza, named after Sappho, is an Aeolic verse form of four lines. Originally composed in quantitative verse and unrhymed, since the Middle Ages imitations of the form typically feature rhyme and accentual prosody. It is "the longest lived of the Classical lyric strophes in the West".

Syllabic verse is a poetic form having a fixed or constrained number of syllables per line, while stress, quantity, or tone play a distinctly secondary role—or no role at all—in the verse structure. It is common in languages that are syllable-timed, such as French or Finnish, as opposed to stress-timed languages such as English, in which accentual verse and accentual-syllabic verse are more common.

Accentual verse has a fixed number of stresses per line regardless of the number of syllables that are present. It is common in languages that are stress-timed, such as English, as opposed to syllabic verse which is common in syllable-timed languages, such as French.

Old Norse poetry encompasses a range of verse forms written in the Old Norse language, during the period from the 8th century to as late as the far end of the 13th century. Old Norse poetry is associated with the area now referred to as Scandinavia. Much Old Norse poetry was originally preserved in oral culture, but the Old Norse language ceased to be spoken and later writing tended to be confined to history rather than for new poetic creation, which is normal for an extinct language. Modern knowledge of Old Norse poetry is preserved by what was written down. Most of the Old Norse poetry that survives was composed or committed to writing in Iceland, after refined techniques for writing were introduced—seemingly contemporaneously with the introduction of Christianity: thus, the general topic area of Old Norse poetry may be referred to as Old Icelandic poetry in literature.

Tail rhyme is a family of stanzaic verse forms used in poetry in French and especially English during and since the Middle Ages, and probably derived from models in medieval Latin versification.

A tribrach is a metrical foot used in formal poetry and Greek and Latin verse. In quantitative meter, it consists of three short syllables occupying a foot, replacing either an iamb or a trochee. In accentual-syllabic verse, the tribrach consists of a run of three short syllables substituted for a trochee.

This is a glossary of poetry terms.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and introduction to poetry:

Higgledy piggledy may refer to:

The double amphibrach is a variation of the double dactyl, similar to the McWhirtle but with stricter formal requirements. Meter and lineation are consistently amphibrachic rather than dactylic, and the shortened fourth and eighth lines rhyme. In narrative sequences, the requirements that the first line be nonsense syllables and second line be a proper name are sometimes waived, but the sixth line requires a single diamphibrachic word.

A masculine ending and feminine ending or weak ending are terms used in prosody, the study of verse form. In general, "masculine ending" refers to a line ending in a stressed syllable; "feminine ending" is its opposite, describing a line ending in a stressless syllable. The terms originate from a grammatical pattern of the French language. When masculine or feminine endings are rhymed with the same type of ending, they respectively result in masculine or feminine rhymes. Poems often arrange their lines in patterns of masculine and feminine endings. The distinction of masculine vs. feminine endings is independent of the distinction between metrical feet.

Aeolic verse is a classification of Ancient Greek lyric poetry referring to the distinct verse forms characteristic of the two great poets of Archaic Lesbos, Sappho and Alcaeus, who composed in their native Aeolic dialect. These verse forms were taken up and developed by later Greek and Roman poets and some modern European poets.

Latin prosody is the study of Latin poetry and its laws of meter. The following article provides an overview of those laws as practised by Latin poets in the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire, with verses by Catullus, Horace, Virgil and Ovid as models. Except for the early Saturnian poetry, which may have been accentual, Latin poets borrowed all their verse forms from the Greeks, despite significant differences between the two languages.

Poetic devices are a form of literary device used in poetry. Poems are created out of poetic devices via a composite of: structural, grammatical, rhythmic, metrical, verbal, and visual elements. They are essential tools that a poet uses to create rhythm, enhance a poem's meaning, or intensify a mood or feeling.

References

- 1 2 3 Anthony Hecht and John Hollander, eds. Jiggery-Pokery, A Compendium of Double Dactyls (New York: Atheneum, 1967)

- ↑ "Drs. P neemt afscheid met een 'ollekebolleke' | NOS". nos.nl. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-16.

- ↑ Reyes, A.T. (poems), Edgar, S.S.O. (notes) and Herrmann, C. (drawings) (2003), Abbreviated lays: stories of ancient Rome, from Aeneas to Pope Gregory I, in double-dactylic rhyme, Oxford: Oxbow Books, ISBN 1842171119 Catalyst Library