Related Research Articles

In social psychology, an interpersonal relation describes a social association, connection, or affiliation between two or more persons. It overlaps significantly with the concept of social relations, which are the fundamental unit of analysis within the social sciences. Relations vary in degrees of intimacy, self-disclosure, duration, reciprocity, and power distribution. The main themes or trends of the interpersonal relations are: family, kinship, friendship, love, marriage, business, employment, clubs, neighborhoods, ethical values, support and solidarity. Interpersonal relations may be regulated by law, custom, or mutual agreement, and form the basis of social groups and societies. They appear when people communicate or act with each other within specific social contexts, and they thrive on equitable and reciprocal compromises.

Romance or romantic love is a feeling of love for, or a strong attraction towards another person, and the courtship behaviors undertaken by an individual to express those overall feelings and resultant emotions.

Infidelity is a violation of a couple's emotional or sexual exclusivity that commonly results in feelings of anger, sexual jealousy, and rivalry.

Open marriage is a form of non-monogamy in which the partners of a dyadic marriage agree that each may engage in extramarital sexual or romantic relationships, without this being regarded by them as infidelity, and consider or establish an open relationship despite the implied monogamy of marriage. There are variant forms of open marriage such as swinging and polyamory, each with the partners having varying levels of input into their spouse's activities.

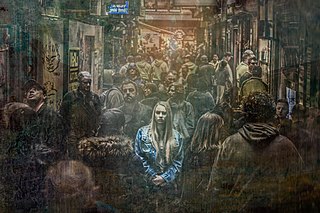

Avoidant personality disorder (AvPD) or anxious personality disorder is a Cluster C personality disorder characterized by excessive social anxiety and inhibition, fear of intimacy, severe feelings of inadequacy and inferiority, and an overreliance on avoidance of feared stimuli as a maladaptive coping method. Those affected typically display a pattern of extreme sensitivity to negative evaluation and rejection, a belief that one is socially inept or personally unappealing to others, and avoidance of social interaction despite a strong desire for it. It appears to affect an approximately equal number of men and women.

A relationship breakup, breakup, or break-up is the ending of a relationship. The act is commonly termed "dumping [someone]" in slang when it is initiated by one partner. The term is less likely to be applied to a married couple, where a breakup is typically called a separation or divorce. When a couple engaged to be married breaks up, it is typically called a "broken engagement". People commonly think of breakups in a romantic aspect, however, there are also non-romantic and platonic breakups, and this type of relationship dissolution is usually caused by failure to maintain a friendship.

An open relationship is an intimate relationship that is sexually non-monogamous. An open relationship generally indicates a relationship where there is a primary emotional and intimate relationship between partners, who agree to at least the possibility of sexual or emotional intimacy with other people. The term "open relationship" is sometimes used interchangeably with the term polyamory, but the two concepts are not identical.

Attachment theory is a psychological and evolutionary framework concerning the relationships between humans, particularly the importance of early bonds between infants and their primary caregivers. Developed by psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby (1907–90), the theory posits that infants need to form a close relationship with at least one primary caregiver to ensure their survival, and to develop healthy social and emotional functioning.

An intimate relationship is an interpersonal relationship that involves emotional or physical closeness between people and may include sexual intimacy and feelings of romance or love. Intimate relationships are interdependent, and the members of the relationship mutually influence each other. The quality and nature of the relationship depends on the interactions between individuals, and is derived from the unique context and history that builds between people over time. Social and legal institutions such as marriage acknowledge and uphold intimate relationships between people. However, intimate relationships are not necessarily monogamous or sexual, and there is wide social and cultural variability in the norms and practices of intimacy between people.

Caring in intimate relationships is the practice of providing care and support to an intimate relationship partner. Caregiving behaviours are aimed at reducing the partner's distress and supporting their coping efforts in situations of either threat or challenge. Caregiving may include emotional support and/or instrumental support. Effective caregiving behaviour enhances the care-recipient's psychological well-being, as well as the quality of the relationship between the caregiver and the care-recipient. However, certain suboptimal caregiving strategies may be either ineffective or even detrimental to coping.

In psychology, the theory of attachment can be applied to adult relationships including friendships, emotional affairs, adult romantic and carnal relationships and, in some cases, relationships with inanimate objects. Attachment theory, initially studied in the 1960s and 1970s primarily in the context of children and parents, was extended to adult relationships in the late 1980s. The working models of children found in Bowlby's attachment theory form a pattern of interaction that is likely to continue influencing adult relationships.

Fear of commitment, also known as gamophobia, is the irrational fear or avoidance of long-term partnership or marriage. The term is sometimes used interchangeably with commitment phobia, which describes a generalized fear or avoidance of commitments more broadly.

Remarriage is a marriage that takes place after a previous marital union has ended, as through divorce or widowhood. Some individuals are more likely to remarry than others; the likelihood can differ based on previous relationship status, level of interest in establishing a new romantic relationship, gender, culture, and age among other factors. Those who choose not to remarry may prefer alternative arrangements like cohabitation or living apart together. Remarriage also provides mental and physical health benefits. However, although remarried individuals tend to have better health than individuals who do not repartner, they still generally have worse health than individuals who have remained continuously married. Remarriage is addressed differently in various religions and denominations of those religions. Someone who repeatedly remarries is referred to as a serial wedder.

The two-body problem is a dilemma for life partners often referred to in academia, relating to the difficulty of both spouses obtaining jobs at the same university, narrow specialism, or within a reasonable commuting distance from each other.

Theories of love can refer to several psychological and sociological theories:

Marriage and health are closely related. Married people experience lower morbidity and mortality across such diverse health threats as cancer, heart attacks, and surgery. There are gender differences in these effects which may be partially due to men's and women's relative status. Most research on marriage and health has focused on heterosexual couples, and more work is needed to clarify the health effects on same-sex marriage. Simply being married, as well as the quality of one's marriage, has been linked to diverse measures of health. Research has examined the social-cognitive, emotional, behavioral and biological processes involved in these links.

Attachment and health is a psychological model which considers how the attachment theory pertains to people's preferences and expectations for the proximity of others when faced with stress, threat, danger or pain. In 1982, American psychiatrist Lawrence Kolb noticed that patients with chronic pain displayed behaviours with their healthcare providers akin to what children might display with an attachment figure, thus marking one of the first applications of the attachment theory to physical health. Development of the adult attachment theory and adult attachment measures in the 1990s provided researchers with the means to apply the attachment theory to health in a more systematic way. Since that time, it has been used to understand variations in stress response, health outcomes and health behaviour. Ultimately, the application of the attachment theory to health care may enable health care practitioners to provide more personalized medicine by creating a deeper understanding of patient distress and allowing clinicians to better meet their needs and expectations.

The Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation (VSA) Model is a framework for conceptualizing the dynamic processes of marriage, created by Benjamin Karney and Thomas Bradbury. The VSA Model emphasizes the consideration of multiple dimensions of functioning, including couple members’ enduring vulnerabilities, experiences of stressful events, and adaptive processes, to account for variations in marital quality and stability over time. The VSA model was a departure from past research considering any one of these themes separately as a contributor to marital outcomes, and integrated these separate factors into a single, cohesive framework in order to best explain how and why marriages change over time. In adherence with the VSA model, in order to achieve a complete understanding of marital phenomenon, research must consider all dimensions of marital functioning, including enduring vulnerabilities, stress, and adaptive processes simultaneously.

A duocentric social network is a type of social network composed of the combined network members of a dyad. The network consists of mutual, overlapping ties between members of the dyad as well as non-mutual ties. While an explicit conceptualization of duocentric social networks appeared for the first time in an academic publication in 2008, the history of the analysis dates back to at least the 1950s and has spanned the fields of psychology, sociology, and health.

Relationship science is an interdisciplinary field dedicated to the scientific study of interpersonal relationship processes. Due to its interdisciplinary nature, relationship science is made-up of researchers of various professional backgrounds within psychology and outside of psychology, but most researchers who identify with the field are psychologists by training. Additionally, the field's emphasis has historically been close and intimate relationships, which includes predominantly dating and married couples, parent-child relationships, and friendships & social networks, but some also study less salient social relationships such as colleagues and acquaintances.

References

- 1 2 3 Bunker, B. B., Zubek, J. M., Vanderslice, V. J., & Rice, R. W. (1992). Quality of life in dual-career families: Commuting versus single-residence couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 399-407.

- 1 2 Rapoport, R., Rapoport, R. N., & Bumstead, J. M. (Eds.). (1978). Working couples. New York: Harper & Row.

- ↑ Gilbert, L. A., & Rachlin, V. (1987). Mental health and psychological functioning of dual-career families. The Counseling Psychologist, 15(1), 7-49.

- ↑ Reed, C. M., & Bruce, W. M. (1993). Dual-career couples in the public sector: A survey of personnel policies and practices. Public Personnel Management.

- ↑ the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 2003.

- ↑ Bergen, K. M., Kirby, E., & McBride, M. C. (2007). "How do you get two houses cleaned?": Accomplishing family caregiving in commuter marriages. Journal of Family Communication, 7, 287-307.

- 1 2 3 4 Anderson, E. A. (1992). Decision-making style: Impact on satisfaction of the commuter couples' lifestyle. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 13(1), 5-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Anderson, E. A., & Spruill, J. W. (1993). "The dual-career commuter family: A lifestyle on the move". Marriage & Family Review, 19(1-2), 131-147.

- 1 2 Gerstel, N., & Gross, H. E. (1984). Commuter marriages: A study of work and family. New York: Guilford.

- ↑ van der Klis, M., & Mulder, C. H. (2008). Beyond the trailing spouse: the commuter partnership as an alternative to family migration. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 23(1), 1-19.

- ↑ Jackson, A. P., Brown, R. P., & Patterson-Stewart, K. E. (2000). African Americans in Dual-Career Commuter Marriages: An Investigation of Their Experiences. The Family Journal, 8, 22-36.

- ↑ Lindemann, Danielle J. (2019). Commuter spouses : new families in a changing world. Ithaca [New York]. ISBN 978-1-5017-3120-4. OCLC 1051775204.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Groves, M. M., & Horm-Wingerd, D. M. (1991). Commuter marriages: Personal, family and career issues. Sociology and social research, 75(4), 212-217.

- 1 2 3 4 Magnuson, S., & Norem, K. (1999). Challenges for higher education couples in commuter marriages: Insights for couples and counselors who work with them. The Family Journal, 7(2), 125-134.

- 1 2 Winfield, F. E. (1985). Commuter marriage: Living together apart. New York: Columbia University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 Jackson, A. P., Brown, R. P., & Patterson-Stewart, K. E. (2000). African Americans in dual-career commuter marriages: An investigation of their experiences. The Family Journal, 8(1), 22-36.

- ↑ Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent development in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 67-92.

- ↑ Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human relations, 7(2), 117-140.

- 1 2 Gross, H. E. (1980). Dual-career couples who live apart: Two types. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 567-576.

- ↑ Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base. New York: Basic.

- ↑ Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Vol. I: Attachment. New York, Basic Books.

- ↑ Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. II: Separation. New York: Basic Books.

- 1 2 Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford.

- ↑ Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226–244.

- ↑ Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York: Guilford.

- 1 2 Pistole, M. C., Roberts, A. & Chapman, M. L. (2010). Attachment, relationship maintenance, and stress in long distance and geographically close romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(4), 535-552.

- ↑ Levy, K. N., Blatt, S. J., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Attachment styles and parental representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 407.

- ↑ Van der Klis, M. & Karsten, L. (2009). Commuting partners, dual residences and the meaning of home. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29, 235-245.

- ↑ Rotter, J. C., Barnett, D. E., & Fawcett, M. L. (1998). On the road again: Dual-career commuter relationships. The Family Journal, 6(1), 46-48.

- ↑ Bettner, B. L., & Lew, A. (1992). Raising kids who can: Using family meetings to nurture responsible, cooperative, caring, and happy children. New York: Harper Perennial.

- ↑ Gerhart-Brooks, D. R., & Lyle, R. R. (1999). The family meeting: Facilitating dialogue with divorced families. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 10(2), 77-82.

- ↑ Johnson, S. E. (1987). Weaving the Threads: Equalizing Professional and Personal Demands Faced by Commuting Career Couples. Journal of the National Association of Women Deans, Administrators, and Counselors, 50(2), 3-10.