Related Research Articles

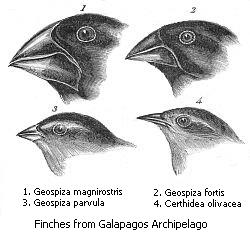

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic interactions or opens new environmental niches. Starting with a single ancestor, this process results in the speciation and phenotypic adaptation of an array of species exhibiting different morphological and physiological traits. The prototypical example of adaptive radiation is finch speciation on the Galapagos, but examples are known from around the world.

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates throughout the world. They range from 1.6 to 60 centimetres.

Lizard is the common name used for all squamate reptiles other than snakes, encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The grouping is paraphyletic as some lizards are more closely related to snakes than they are to other lizards. Lizards range in size from chameleons and geckos a few centimeters long to the 3-meter-long Komodo dragon.

Gekkonidae is the largest family of geckos, containing over 950 described species in 64 genera. The Gekkonidae contain many of the most widespread gecko species, including house geckos (Hemidactylus), the tokay gecko (Gekko), day geckos (Phelsuma), the mourning gecko (Lepidodactylus), and dtellas (Gehyra). Gekkonid geckos occur globally and are particularly diverse in tropical areas.

Dactyloidae are a family of lizards commonly known as anoles and native to warmer parts of the Americas, ranging from southeastern United States to Paraguay. Instead of treating it as a family, some authorities prefer to treat it as a subfamily, Dactyloinae, of the family Iguanidae. In the past they were included in the family Polychrotidae together with Polychrus, but the latter genus is not closely related to the true anoles.

Anolis is a genus of anoles, iguanian lizards in the family Dactyloidae, native to the Americas. With more than 425 species, it represents the world's most species-rich amniote tetrapod genus, although many of these have been proposed to be moved to other genera, in which case only about 45 Anolis species remain. Previously, it was classified under the family Polychrotidae that contained all the anoles, as well as Polychrus, but recent studies place it in the Dactyloidae.

Anolis carolinensis or green anole is a tree-dwelling species of anole lizard native to the southeastern United States and introduced to islands in the Pacific and Caribbean. A small to medium-sized lizard, the green anole is a trunk-crown ecomorph and can change its color to several shades from brown to green.

Autotomy or 'self-amputation', is the behaviour whereby an animal sheds or discards one or more of its own appendages, usually as a self-defense mechanism to elude a predator's grasp or to distract the predator and thereby allow escape. Some animals have the ability to regenerate the lost body part later. Autotomy has multiple evolutionary origins and is thought to have evolved at least nine times independently in animals. The term was coined in 1883 by Leon Fredericq.

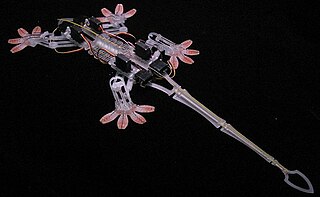

Synthetic setae emulate the setae found on the toes of a gecko and scientific research in this area is driven towards the development of dry adhesives. Geckos have no difficulty mastering vertical walls and are apparently capable of adhering themselves to just about any surface. The five-toed feet of a gecko are covered with elastic hairs called setae and the ends of these hairs are split into nanoscale structures called spatulae. The sheer abundance and proximity to the surface of these spatulae make it sufficient for van der Waals forces alone to provide the required adhesive strength. Following the discovery of the gecko's adhesion mechanism in 2002, which is based on van der Waals forces, biomimetic adhesives have become the topic of a major research effort. These developments are poised to yield families of novel adhesive materials with superior properties which are likely to find uses in industries ranging from defense and nanotechnology to healthcare and sport.

Island gigantism, or insular gigantism, is a biological phenomenon in which the size of an animal species isolated on an island increases dramatically in comparison to its mainland relatives. Island gigantism is one aspect of the more general "island effect" or "Foster's rule", which posits that when mainland animals colonize islands, small species tend to evolve larger bodies, and large species tend to evolve smaller bodies. This is itself one aspect of the more general phenomenon of island syndrome which describes the differences in morphology, ecology, physiology and behaviour of insular species compared to their continental counterparts. Following the arrival of humans and associated introduced predators, many giant as well as other island endemics have become extinct. A similar size increase, as well as increased woodiness, has been observed in some insular plants such as the Mapou tree in Mauritius which is also known as the "Mauritian baobab" although it is member of the grape family (Vitaceae).

Evolutionary physiology is the study of the biological evolution of physiological structures and processes; that is, the manner in which the functional characteristics of individuals in a population of organisms have responded to natural selection across multiple generations during the history of the population. It is a sub-discipline of both physiology and evolutionary biology. Practitioners in the field come from a variety of backgrounds, including physiology, evolutionary biology, ecology, and genetics.

Phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) use information on the historical relationships of lineages (phylogenies) to test evolutionary hypotheses. The comparative method has a long history in evolutionary biology; indeed, Charles Darwin used differences and similarities between species as a major source of evidence in The Origin of Species. However, the fact that closely related lineages share many traits and trait combinations as a result of the process of descent with modification means that lineages are not independent. This realization inspired the development of explicitly phylogenetic comparative methods. Initially, these methods were primarily developed to control for phylogenetic history when testing for adaptation; however, in recent years the use of the term has broadened to include any use of phylogenies in statistical tests. Although most studies that employ PCMs focus on extant organisms, many methods can also be applied to extinct taxa and can incorporate information from the fossil record.

The Dalmatian wall lizard is a species of lizard in the family Lacertidae. It is found in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Italy, Serbia, Montenegro, and Slovenia. Its natural habitats are temperate forests, Mediterranean-type shrubby vegetation, rocky areas, and pastureland.

The Italian wall lizard or ruin lizard is a species of lizard in the family Lacertidae. P. siculus is native to south and southeastern Europe, but has also been introduced elsewhere in the continent, as well as North America, where it is a possible invasive species. P. siculus is a habitat generalist and can thrive in natural and human-modified environments. Similarly, P. siculus has a generalized diet as well, allowing it to have its large range.

Lizards are among the most diverse groups of reptiles with more than 5,600 species. With such diversity in physical and behavioral characteristics, lizards have evolved many different ways to communicate. Lizards communicate to gain information about the individuals around them by paying attention to various characteristics exhibited by individuals and using various physical and behavioral traits to communicate. These traits differ based on the mode of communication being used.

Kevin de Queiroz is a vertebrate, evolutionary, and systematic biologist. He has worked in the phylogenetics and evolutionary biology of squamate reptiles, the development of a unified species concept and of a phylogenetic approach to biological nomenclature, and the philosophy of systematic biology.

Jonathan B. Losos is an American evolutionary biologist and Herpetologist.

Eichstaettisaurus is a genus of lizards from the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous of Germany, Spain, and Italy. With a flattened head, forward-oriented and partially symmetrical feet, and tall claws, Eichstaettisaurus bore many adaptations to a climbing lifestyle approaching those of geckoes. The type species, E. schroederi, is among the oldest and most complete members of the Squamata, being known by one specimen originating from the Tithonian-aged Solnhofen Limestone of Germany. A second species, E. gouldi, was described from another skeleton found in the Matese Mountains of Italy. Despite being very similar to E. schroederi, it lived much later, during the Albian stage. Fossils of both species show exceptional preservation due to deposition in low-oxygen marine environments.

The Vinales anole, also known as the Cuban stream anole, is a species of lizard in the family Dactyloidae, endemic to Cuba.

Bradfield's Namib day gecko is a species of lizard in the family Gekkonidae. The species is endemic to Namibia. This species was first described in 1935 by the British-born, South African zoologist John Hewitt, who gave it the name Rhoptropus bradfieldi in honour of the South African naturalist and collector R.D. Bradfield (1882–1949).

References

- ↑ "Duncan J. Irschick". University of Massachusetts at Amherst. 28 September 2009. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ↑ Judson, Olivia (July 22, 2008). "A Natural Selection Science Writer". The New York Times .

- ↑ Irschick, D. J., Austin, C. C., Petren, K., Fisher, R. N., Losos, J. B., Ellers, O. 1996. A comparative analysis of clinging ability among pad-bearing lizards. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 59:21-35.

- ↑ "Discovery Channel Cable Show about Gecko Adhesion, which includes some of Duncan Irschick's work". Archived from the original on 2009-06-03. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ Michael D. Bartlett; Andrew B. Croll; Daniel R. King; Beth M. Paret; Duncan J. Irschick; Alfred J. Crosby (2012). "Biomimetics: Looking Beyond Fibrillar Features to Scale Gecko-Like Adhesion (Adv. Mater. 8/2012)". Advanced Materials. 24 (8): 1078. Bibcode:2012AdM....24..994B. doi:10.1002/adma.201290037.

- ↑ "Inspired by gecko feet, scientists invent super-adhesive material". Phys.org . February 16, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ↑ Herrel, A., Huyghe, K., Vanhooydonck, B., Backeljau, T., Breugelmans, K., Grbac, I., Van Damme, R., Irschick, D. J. 2008. Rapid large scale evolutionary divergence in morphology and performance associated with the exploitation of a novel dietary resource in the lizard Podarcissicula. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105:4792-4795.

- ↑ Richard Dawkins. The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution. Free Press (United States), Transworld (United Kingdom and Commonwealth). 2009. ISBN 0-593-06173-X.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl The Tangled Bank: An Introduction to Evolution(2009) ISBN 0-9815194-7-4.

- ↑ "Editorial Board". Functional Ecology. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ↑ "The Quarterly Review of Biology". University of Chicago Press. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ↑ "The Hilgendorf Lecture". Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2019.