The Indian Independence Movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

Gopal Krishna Gokhale was an Indian political leader and a social reformer during the Indian independence movement, and political mentor of Indian freedom fighter Mahatma Gandhi.

Dadabhai Naoroji, also known as the "Grand Old Man of India" and "Unofficial Ambassador of India", was an Indian Independence activist, political leader, merchant, scholar and writer who served as 2nd, 9th, and 22nd President of the Indian National Congress from 1886 to 1887, 1893 to 1894 and 1906 to 1907.

The Indian Councils Act 1909, commonly known as the Morley–Minto or Minto–Morley Reforms, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that brought about a limited increase in the involvement of Indians in the governance of British India. Named after Viceroy Lord Minto and Secretary of State John Morley, the act introduced elections to legislative councils and admitted Indians to councils of the Secretary of State for India, the viceroy, and to the executive councils of Bombay and Madras states. Muslims were granted separate electorates according to the demands of the Muslim League.

The Indian Home Rule movement was a movement in British India on the lines of the Irish Home Rule movement and other home rule movements. The movement lasted around two years between 1916–1918 and is believed to have set the stage for the independence movement under the leadership of Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak to the educated English speaking upper class Indians. In 1920 All India Home Rule League changed its name to Swarajya Sabha.

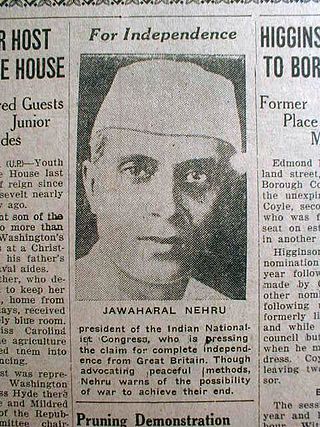

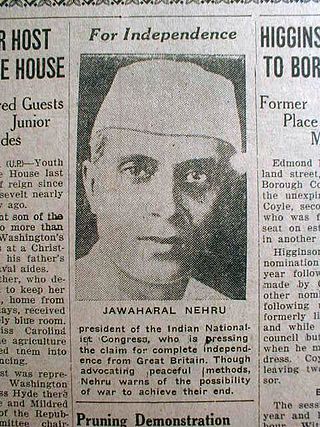

Indian nationalism is an instance of territorial nationalism, which is inclusive of all of the people of India, despite their diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Indian nationalism can trace roots to pre-colonial India, but was fully developed during the Indian independence movement which campaigned for independence from British rule. Indian nationalism quickly rose to popularity in India through these united anti-colonial coalitions and movements. Independence movement figures like Mahatma Gandhi, Subhas Chandra Bose, and Jawaharlal Nehru spearheaded the Indian nationalist movement. After Indian Independence, Nehru and his successors continued to campaign on Indian nationalism in face of border wars with both China and Pakistan. After the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971 and the Bangladesh Liberation War, Indian nationalism reached its post-independence peak. However by the 1980s, religious tensions reached a melting point and Indian nationalism sluggishly collapsed in the following decades. Despite its decline and the rise of religious nationalism, Indian nationalism and its historic figures continue to strongly influence the politics of India and reflect an opposition to the sectarian strands of Hindu nationalism and Muslim nationalism.

The first Partition of Bengal (1905) was a territorial reorganization of the Bengal Presidency implemented by the authorities of the British Raj. The reorganization separated the largely Muslim eastern areas from the largely Hindu western areas. Announced on 16 July 1905 by Lord Curzon, then Viceroy of India, and implemented West Bengal for Hindus and East Bengal for Muslims, it was undone a mere six years later. The nationalists saw the partition as a challenge to Indian nationalism and as a deliberate attempt to divide the Bengal Presidency on religious grounds, with a Muslim majority in the east and a Hindu majority in the west. The Hindus of West Bengal complained that the division would make them a minority in a province that would incorporate the province of Bihar and Orissa. Hindus were outraged at what they saw as a "divide and rule" policy, even though Curzon stressed it would produce administrative efficiency. The partition animated the Muslims to form their own national organization along communal lines. To appease Bengali sentiment, Bengal was reunited by King George V in 1911, in response to the Swadeshi movement's riots in protest against the policy.

The Liberal Party of India was a political organization espousing liberalism in the politics of India.

The Declaration of Purna Swaraj was a resolution which was passed in 1930 because of the dissatisfaction among the Indian masses regarding the British offer of Dominion status to India. The word Purna Swaraj was derived from Sanskrit पूर्ण (Pūrṇa) 'Complete' and स्वराज (Svarāja) 'Self-rule or Sovereignty', or Declaration of the Independence of India, it was promulgated by the Indian National Congress, resolving the Congress and Indian nationalists to fight for Purna Swaraj, or complete self-rule/total independence from the British rule.

SirSurendranath Banerjee, often known as Rashtraguru was Indian nationalist leader during the British Rule. He founded a nationalist organization called the Indian National Association to bring Hindus and Muslims together for political action. He was one of the founding members of the Indian National Congress. Surendranath supported Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms, unlike Congress, and with many liberal leaders he left Congress and founded a new organisation named Indian National Liberation Federation in 1919.

Alfred John Webb was an Irish Quaker from a family of activist printers. He became an Irish Parliamentary Party politician and Member of Parliament (MP), as well as a participant in nationalist movements around the world. He supported Butt's Home Government Association and the United Irish League. At Madras in 1894, he became the third non-Indian to preside over the Indian National Congress.

India House was a student residence that existed between 1905 and 1910 at Cromwell Avenue in Highgate, North London. With the patronage of lawyer Shyamji Krishna Varma, it was opened to promote nationalist views among Indian students in Britain. This institute used to grant scholarships to Indian youths for higher studies in England. The building rapidly became a hub for political activism, one of the most prominent for overseas revolutionary Indian nationalism. "India House" came to informally refer to the nationalist organisations that used the building at various times.

Womesh Chunder Bonnerjee (or Umesh Chandra Banerjee was an Indian Independence activist, and barrister who practiced in England. He was a secretary of the London Indian society founded by Dadabhai Naoroji in 1865. He was a co-founder and the first president of Indian National Congress in 1885 at Bombay, served again as president in 1892 at Allahabad. Bonnerjee financed the British Committee of Congress and its journals in London. Along with Naoroji, Eardley Norton and William Digby he started the Congress Political Agency, a branch of Congress in London. He unsuccessfully contested the 1892 United Kingdom general election as a Liberal party candidate for the Barrow and Furness seat. In 1893, Naoroji, Bonnerjee and Badruddin Tyabji founded the Indian Parliamentary Committee in England.

The Indian Home Rule Society (IHRS) was an Indian organisation founded in London in 1905 that sought to promote the cause of self-rule in British India. The organisation was founded by Shyamji Krishna Varma, with support from a number of prominent Indian nationalists in Britain at the time, including Bhikaji Cama, Dadabhai Naoroji and S.R. Rana, and was intended to be a rival organisation to the British Committee of the Indian National Congress that was the main avenue of the loyalist opinion at the time.

Hindu Revolution is a term in Hindu nationalism referring to a sociopolitical movement aiming to overthrow untouchability and casteism to unified social and political community to create the foundations of a modern nation.

Dadabhai Naoroji Road (D.N.Road), a North–South commercial artery road, in the Fort business district in South Mumbai of Maharashtra, India, is the nerve centre of the city, starting from the Mahatma Phule Market ,linking Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus, leads to the Hutatma Chowk at the southern end of the road. This entire stretch of the road is studded with Neo–Classical and Gothic Revival buildings and parks built in the 19th century, intermingled with modern office buildings and commercial establishments.

Perin Ben Captain (1888–1958) was an Indian freedom activist, social worker, and the grand daughter of renowned Indian intellectual and leader, Dadabhai Naoroji. The Government of India honoured her in 1954 with the award of Padma Shri, the fourth highest Indian civilian award for her contributions to the country, placing her among the first group of recipients of the award.

The British Committee of the Indian National congress was an organization established in Britain by the Indian National Congress in 1889. Its purpose was to raise awareness of Indian issues to the public in Britain, to whom the Government of India was responsible. It followed the work of W.C. Bonnerjee and Dadabhoi Naoroji, who raised India related issues in the British parliament through the support of radical MPs like Charles Bradlaugh. William Wedderburn served as the first chairmanship and William Digby as secretary.

The Legislatures of British India included legislative bodies in the presidencies and provinces of British India, the Imperial Legislative Council, the Chamber of Princes and the Central Legislative Assembly. The legislatures were created under Acts of Parliament of the United Kingdom. Initially serving as small advisory councils, the legislatures evolved into partially elected bodies, but were never elected through suffrage. Provincial legislatures saw boycotts during the period of dyarchy between 1919 and 1935. After reforms and elections in 1937, the largest parties in provincial legislatures formed governments headed by a prime minister. A few British Indian subjects were elected to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which had superior powers than colonial legislatures. British Indian legislatures did not include Burma's legislative assembly after 1937, the State Council of Ceylon nor the legislative bodies of princely states.

The Women's suffrage movement in India fought for Indian women's right to political enfranchisement in Colonial India under British rule. Beyond suffrage, the movement was fighting for women's right to stand for and hold office during the colonial era. In 1918, when Britain granted limited suffrage to women property holders, the law did not apply to British citizens in other parts of the Empire. Despite petitions presented by women and men to the British commissions sent to evaluate Indian voting regulations, women's demands were ignored in the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms. In 1919, impassioned pleas and reports indicating support for women to have the vote were presented by suffragists to the India Office and before the Joint Select Committee of the House of Lords and Commons, who were meeting to finalize the electoral regulation reforms of the Southborough Franchise Committee. Though they were not granted voting rights, nor the right to stand in elections, the Government of India Act 1919 allowed Provincial Councils to determine if women could vote, provided they met stringent property, income, or educational levels.