Related Research Articles

The Holocene is the current geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene together form the Quaternary period. The Holocene is an interglacial period within the ongoing glacial cycles of the Quaternary, and is equivalent to Marine Isotope Stage 1.

The Holocene extinction, also referred to as the Anthropocene extinction, is an ongoing extinction event caused by human activities during the Holocene epoch. This extinction event spans numerous families of plants and animals, including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates, impacting both terrestrial and marine species. Widespread degradation of biodiversity hotspots such as coral reefs and rainforests has exacerbated the crisis. Many of these extinctions are undocumented, as the species are often undiscovered before their extinctions.

The Quaternary is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), as well as the current and most recent of the twelve periods of the Phanerozoic eon. It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million years ago to the present. The Quaternary Period is divided into two epochs: the Pleistocene and the Holocene ; a proposed third epoch, the Anthropocene, was rejected in 2024 by IUGS, the governing body of the ICS.

Climate variability includes all the variations in the climate that last longer than individual weather events, whereas the term climate change only refers to those variations that persist for a longer period of time, typically decades or more. Climate change may refer to any time in Earth's history, but the term is now commonly used to describe contemporary climate change, often popularly referred to as global warming. Since the Industrial Revolution, the climate has increasingly been affected by human activities.

Paleoclimatology is the scientific study of climates predating the invention of meteorological instruments, when no direct measurement data were available. As instrumental records only span a tiny part of Earth's history, the reconstruction of ancient climate is important to understand natural variation and the evolution of the current climate.

The Anthropocene is a now rejected proposal for the name of a geological epoch that would follow the Holocene, dating from the commencement of significant human impact on Earth up to the present day. It was rejected in 2024 by the International Commission on Stratigraphy in terms of being a defined geologic period. The impacts of humans affect Earth's oceans, geology, geomorphology, landscape, limnology, hydrology, ecosystems and climate. The effects of human activities on Earth can be seen for example in biodiversity loss and climate change. Various start dates for the Anthropocene have been proposed, ranging from the beginning of the Neolithic Revolution, to as recently as the 1960s. The biologist Eugene F. Stoermer is credited with first coining and using the term anthropocene informally in the 1980s; Paul J. Crutzen re-invented and popularized the term. However, in 2024 the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) and the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) rejected the Anthropocene Epoch proposal for inclusion in the Geologic Time Scale.

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an increasingly large population possible. These settled communities permitted humans to observe and experiment with plants, learning how they grew and developed. This new knowledge led to the domestication of plants into crops.

The Flandrian interglacial or stage is the regional name given by geologists and archaeologists in the British Isles to the period from around 12,000 years ago, at the end of the last glacial period, to the present day. As such, it is in practice identical in span to the Holocene.

The faint young Sun paradox or faint young Sun problem describes the apparent contradiction between observations of liquid water early in Earth's history and the astrophysical expectation that the Sun's output would have been only 70 percent as intense during that epoch as it is during the modern epoch. The paradox is this: with the young Sun's output at only 70 percent of its current output, early Earth would be expected to be completely frozen, but early Earth seems to have had liquid water and supported life.

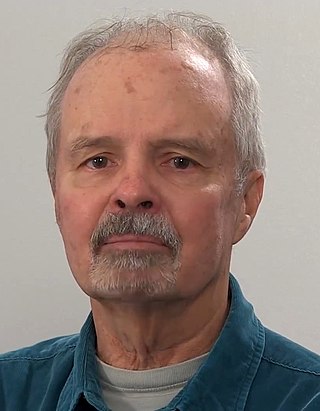

William F. Ruddiman is a palaeoclimatologist and Professor Emeritus at the University of Virginia. Ruddiman earned an undergraduate degree in geology in 1964 at Williams College, and a Ph.D. in marine geology from Columbia University in 1969. Ruddiman worked at the US Naval Oceanographic Office from 1969 to 1976, and at Columbia's Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory from 1976 to 1991. He moved to Virginia in 1991, serving as a professor in Environmental Sciences. Ruddiman's research interests center on climate change over several time scales. He is a Fellow of both the Geological Society of America and the American Geophysical Union. Ruddiman has participated in 15 oceanographic cruises, and was co-chief of two deep-sea drilling cruises.

Plows, Plagues and Petroleum: How Humans Took Control of Climate is a 2005 book published by Princeton University Press and written by William Ruddiman, a paleoclimatologist and Professor Emeritus at the University of Virginia. He has authored and co-authored several books and academic papers on the subject of climate change. Scientists often refer to this period as the "Anthropocene" and define it as the era in which humans first began to alter the Earth's climate and ecosystems. Ruddiman contends that human induced climate change began as a result of the advent of agriculture thousands of years ago and resulted in warmer temperatures that could have possibly averted another ice age; this is the early anthropocene hypothesis.

Throughout Earth's climate history (Paleoclimate) its climate has fluctuated between two primary states: greenhouse and icehouse Earth. Both climate states last for millions of years and should not be confused with the much smaller glacial and interglacial periods, which occur as alternating phases within an icehouse period and tend to last less than one million years. There are five known icehouse periods in Earth's climate history, namely the Huronian, Cryogenian, Andean-Saharan, Late Paleozoic and Late Cenozoic glaciations.

The Subatlantic is the current climatic age of the Holocene epoch. It started about 2,500 years BP and is still ongoing. Its average temperatures are slightly lower than during the preceding Subboreal and Atlantic. During its course, the temperature underwent several oscillations, which had a strong influence on fauna and flora and thus indirectly on the evolution of human civilizations. With intensifying industrialisation, human society started to stress the natural climatic cycles with increased greenhouse gas emissions.

Planetary boundaries are a framework to describe limits to the impacts of human activities on the Earth system. Beyond these limits, the environment may not be able to self-regulate anymore. This would mean the Earth system would leave the period of stability of the Holocene, in which human society developed. The framework is based on scientific evidence that human actions, especially those of industrialized societies since the Industrial Revolution, have become the main driver of global environmental change. According to the framework, "transgressing one or more planetary boundaries may be deleterious or even catastrophic due to the risk of crossing thresholds that will trigger non-linear, abrupt environmental change within continental-scale to planetary-scale systems."

Deglaciation is the transition from full glacial conditions during ice ages, to warm interglacials, characterized by global warming and sea level rise due to change in continental ice volume. Thus, it refers to the retreat of a glacier, an ice sheet or frozen surface layer, and the resulting exposure of the Earth's surface. The decline of the cryosphere due to ablation can occur on any scale from global to localized to a particular glacier. After the Last Glacial Maximum, the last deglaciation begun, which lasted until the early Holocene. Around much of Earth, deglaciation during the last 100 years has been accelerating as a result of climate change, partly brought on by anthropogenic changes to greenhouse gases.

John E. Kutzbach was an American climate scientist who pioneered the use of climate models to investigate the causes and effects of large changes of climate of the past.

The Late Cenozoic Ice Age, or Antarctic Glaciation, began 34 million years ago at the Eocene-Oligocene Boundary and is ongoing. It is Earth's current ice age or icehouse period. Its beginning is marked by the formation of the Antarctic ice sheets.

The means by which agriculture expanded into the Philippines is argued by many different anthropologists and an exact date of its origin is unknown. However, there are proxy indicators and other pieces of evidence that allow anthropologists to get an idea of when different crops reached the Philippines and how they may have gotten there. Rice is an important agricultural crop today in the Philippines and many countries throughout the world import rice and other products from the Philippines.

The Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) is an interdisciplinary research group dedicated to the study of the Anthropocene as a geological time unit. It was established in 2009 as part of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS), a constituent body of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). As of 2021, the research group features 37 members, with the physical geographer Simon Turner as Secretary and the geologist Colin Neil Waters as chair of the group. The late Nobel Prize-winning Paul Crutzen, who popularized the word 'Anthropocene' in 2000, had also been a member of the group until he died on January 28, 2021. The main goal of the AWG is providing scientific evidence robust enough for the Anthropocene to be formally ratified by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) as an epoch within the Geologic time scale.

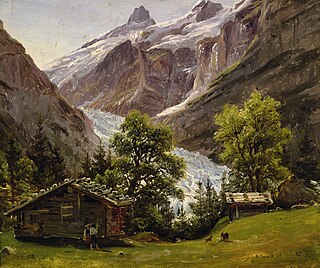

The Grindelwald Fluctuation is a period when glaciers in Grindelwald, Switzerland, expanded significantly. Temperatures were 1-2 degrees Celsius lower than twentieth-century averages during this period, which is thought to have lasted from the 1560s to the 1630s.

References

- ↑ Ruddiman, William F. (2003). "The anthropogenic greenhouse era began thousands of years ago" (PDF). Climatic Change. 61 (3): 261–293. Bibcode:2003ClCh...61..261R. doi:10.1023/B:CLIM.0000004577.17928.fa. S2CID 2501894 . Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ↑ Lewis, Simon L. (2018). Human planet : how we created the anthropocene. Mark A. Maslin. UK. ISBN 978-0-241-28088-1. OCLC 1038430807.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Davis, Heather; Todd, Zoe (2017-12-20). "On the Importance of a Date, or, Decolonizing the Anthropocene". ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies. 16 (4): 761–780. ISSN 1492-9732.

- ↑ Keeler, Kyle (2020-09-08). "Colonial Theft and Indigenous Resistance in the Kleptocene". Edge Effects. Retrieved 2021-09-08.

- ↑ Ruddiman, William F. (31 October 2007). "The early anthropogenic hypothesis: Challenges and responses" (PDF). Reviews of Geophysics. 45 (4). American Geophysical Union (AGU). Bibcode:2007RvGeo..45.4001R. doi:10.1029/2006rg000207. ISSN 8755-1209. S2CID 129451880 . Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Bocquet-Appel (July 29, 2011). "When the World's Population Took Off: The Springboard of the Neolithic Demographic Transition". Science. 333 (6042): 560–561. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..560B. doi:10.1126/science.1208880. PMID 21798934. S2CID 29655920.

- ↑ "International Stratigraphic Chart". International Commission on Stratigraphy. Archived from the original on 2013-02-12. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ↑ Graeme Barker (25 March 2009). The Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory: Why did Foragers become Farmers?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955995-4 . Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ↑ Zalasiewicz, Jan; Waters, Colin N; Head, Martin J; Poirier, Clément; Summerhayes, Colin P; Leinfelder, Reinhold; Grinevald, Jacques; Steffen, Will; Syvitski, Jaia; Haff, Peter; McNeill, John R (June 2019). "A formal Anthropocene is compatible with but distinct from its diachronous anthropogenic counterparts: a response to W.F. Ruddiman's 'three flaws in defining a formal Anthropocene'". Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment. 43 (3): 319–333. Bibcode:2019PrPG...43..319Z. doi:10.1177/0309133319832607. hdl: 11250/2608779 . ISSN 0309-1333. S2CID 146737824.

- ↑ DeLoughrey, Elizabeth M. (2019). Allegories of the Anthropocene. Duke University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4780-0410-3. OCLC 1048935653.

- 1 2 Keeler, Kyle (9 August 2021). "Before colonization (BC) and after decolonization (AD): The Early Anthropocene, the Biblical Fall, and relational pasts, presents, and futures". Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space. 5 (3): 1341–1360. doi:10.1177/25148486211033087. ISSN 2514-8486. S2CID 238671275.

- ↑ Boyle, J.F.; Gaillard, M.-J.; Kaplan, J.O. & Dearing, J.A. (2011). "Modelling prehistoric land use and carbon budgets: A critical review". The Holocene. 21 (5): 715–722. Bibcode:2011Holoc..21..715B. doi:10.1177/0959683610386984. S2CID 129590170.

- ↑ Certini, G. & Scalenghe, R. (2015). "Holocene as Anthropocene". Science. 349 (6245): 246. doi:10.1126/science.349.6245.246-a. hdl: 2158/1006256 . PMID 26185234.

- ↑ Zalasiewicz, Jan; Waters, Colin N.; Head, Martin J.; Poirier, Clément; Summerhayes, Colin P.; Leinfelder, Reinhold; et al. (June 2019). "A formal Anthropocene is compatible with but distinct from its diachronous anthropogenic counterparts: A response to W.F. Ruddiman's 'three flaws in defining a formal Anthropocene'". Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment. 43 (3): 319–333. Bibcode:2019PrPG...43..319Z. doi:10.1177/0309133319832607. hdl: 11250/2608779 . ISSN 0309-1333. S2CID 146737824.

- ↑ DeLoughrey, Elizabeth M. (June 2019). Allegories of the Anthropocene. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-0558-2. OCLC 1081380012.