Related Research Articles

An earthquake – also called a quake, tremor, or temblor – is the shaking of the Earth's surface resulting from a sudden release of energy in the lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from those so weak they cannot be felt, to those violent enough to propel objects and people into the air, damage critical infrastructure, and wreak destruction across entire cities. The seismic activity of an area is the frequency, type, and size of earthquakes experienced over a particular time. The seismicity at a particular location in the Earth is the average rate of seismic energy release per unit volume.

The San Andreas Fault is a continental right-lateral strike-slip transform fault that extends roughly 1,200 kilometers (750 mi) through the U.S. state of California. It forms part of the tectonic boundary between the Pacific plate and the North American plate. Traditionally, for scientific purposes, the fault has been classified into three main segments, each with different characteristics and a different degree of earthquake risk. The average slip rate along the entire fault ranges from 20 to 35 mm per year.

A transform fault or transform boundary, is a fault along a plate boundary where the motion is predominantly horizontal. It ends abruptly where it connects to another plate boundary, either another transform, a spreading ridge, or a subduction zone. A transform fault is a special case of a strike-slip fault that also forms a plate boundary.

In seismology, an aftershock is a smaller earthquake that follows a larger earthquake, in the same area of the main shock, caused as the displaced crust adjusts to the effects of the main shock. Large earthquakes can have hundreds to thousands of instrumentally detectable aftershocks, which steadily decrease in magnitude and frequency according to a consistent pattern. In some earthquakes the main rupture happens in two or more steps, resulting in multiple main shocks. These are known as doublet earthquakes, and in general can be distinguished from aftershocks in having similar magnitudes and nearly identical seismic waveforms.

The North American plate is a tectonic plate containing most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of 76 million km2 (29 million sq mi), it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Pacific plate.

The Juan de Fuca plate is a small tectonic plate (microplate) generated from the Juan de Fuca Ridge that is subducting beneath the northerly portion of the western side of the North American plate at the Cascadia subduction zone. It is named after the explorer of the same name. One of the smallest of Earth's tectonic plates, the Juan de Fuca plate is a remnant part of the once-vast Farallon plate, which is now largely subducted underneath the North American plate.

Parkfield is an unincorporated community in Monterey County, California. It is located on Little Cholame Creek 21 miles (34 km) east of Bradley, at an elevation of 1,529 feet (466 m). As of 2007, road signs announce the population as 18.

The New Madrid seismic zone (NMSZ), sometimes called the New Madrid fault line, is a major seismic zone and a prolific source of intraplate earthquakes in the Southern and Midwestern United States, stretching to the southwest from New Madrid, Missouri.

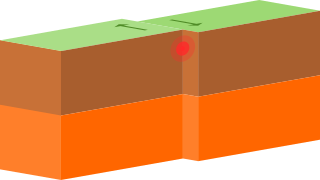

A volcano tectonic earthquake or volcano earthquake is caused by the movement of magma beneath the surface of the Earth. The movement results in pressure changes where the rock around the magma has a change in stress. At some point, this stress can cause the rock to break or move. This seismic activity is used by scientists to monitor volcanoes. The earthquakes may also be related to dike intrusion and/or occur as earthquake swarms. Usually they are characterised by high seismic frequency and lack the pattern of a main shock followed by a decaying aftershock distribution of fault related tectonic earthquakes.

Parkfield earthquake is a name given to various large earthquakes that occurred in the vicinity of the town of Parkfield, California, United States. The San Andreas fault runs through this town, and six successive magnitude 6 earthquakes occurred on the fault at unusually regular intervals, between 12 and 32 years apart, between 1857 and 1966. The latest major earthquake in the region struck on September 28, 2004.

The Cascadia subduction zone is a 960 km (600 mi) fault at a convergent plate boundary, about 100–200 km (70–100 mi) off the Pacific coast, that stretches from northern Vancouver Island in Canada to Northern California in the United States. It is capable of producing 9.0+ magnitude earthquakes and tsunamis that could reach 30 m (98 ft). The Oregon Department of Emergency Management estimates shaking would last 5–7 minutes along the coast, with strength and intensity decreasing further from the epicenter. It is a very long, sloping subduction zone where the Explorer, Juan de Fuca, and Gorda plates move to the east and slide below the much larger mostly continental North American plate. The zone varies in width and lies offshore beginning near Cape Mendocino, Northern California, passing through Oregon and Washington, and terminating at about Vancouver Island in British Columbia.

In geology, aseismic creep or fault creep is measurable surface displacement along a fault in the absence of notable earthquakes. Aseismic creep may also occur as "after-slip" days to years after an earthquake. Notable examples of aseismic slip include faults in California.

The Mendocino triple junction (MTJ) is the point where the Gorda plate, the North American plate, and the Pacific plate meet, in the Pacific Ocean near Cape Mendocino in northern California. This triple junction is the location of a change in the broad tectonic plate motions which dominate the west coast of North America, linking convergence of the northern Cascadia subduction zone and translation of the southern San Andreas Fault system. This region can be characterized by transform fault movement, the San Andreas also by transform strike slip movement, and the Cascadia subduction zone by a convergent plate boundary subduction movement. The Gorda plate is subducting, towards N50ºE, under the North American plate at 2.5–3 cm/yr, and is simultaneously converging obliquely against the Pacific plate at a rate of 5 cm/yr in the direction N115ºE. The accommodation of this plate configuration results in a transform boundary along the Mendocino fracture zone, and a divergent boundary at the Gorda Ridge. This area is tectonically active historically and today. The Cascadia subduction zone is capable of producing megathrust earthquakes on the order of MW 9.0.

The Newport–Inglewood Fault is a right-lateral strike-slip fault in Southern California. The fault extends for 47 mi (76 km) from Culver City southeast through Inglewood and other coastal communities to Newport Beach at which point the fault extends east-southeast into the Pacific Ocean. The fault comes back on shore in the La Jolla area of San Diego and continues southward to downtown San Diego. In San Diego it is known as the Rose Canyon Fault. The fault can be inferred on the Earth's surface as passing along and through a line of hills extending from Signal Hill to Culver City. The fault has a slip rate of approximately 0.6 mm (0.024 in)/year and is predicted to be capable of a 6.0–7.4 magnitude earthquake on the moment magnitude scale. A 2017 study concluded that, together, the Newport–Inglewood Fault and Rose Canyon Fault could produce an earthquake of 7.3 or 7.4 magnitude.

Earth Revealed: Introductory Geology, originally titled Earth Revealed, is a 26-part video instructional series covering the processes and properties of the physical Earth, with particular attention given to the scientific theories underlying geological principles. The telecourse was produced by Intelecom and the Southern California Consortium, was funded by the Annenberg/CPB Project, and first aired on PBS in 1992 with the title Earth Revealed. All 26 episodes are hosted by Dr. James L. Sadd, professor of environmental science at Occidental College in Los Angeles, California.

The Wabash Valley seismic zone is a tectonic region located in the Midwestern United States, centered on the valley of the lower Wabash River, along the state line between southeastern Illinois and southwestern Indiana.

The Brawley Seismic Zone (BSZ), also known as the Brawley fault zone, is a predominantly extensional tectonic zone that connects the southern terminus of the San Andreas Fault with the Imperial Fault in Southern California. The BSZ is named for the nearby town of Brawley in Imperial County, California, and the seismicity there is characterized by earthquake swarms.

This is a list of different types of earthquake.

The 2013 Saravan earthquake occurred with a moment magnitude of 7.7 at 15:14 pm IRDT (UTC+4:30) on 16 April. The shock struck a mountainous area between the cities of Saravan and Khash in Sistan and Baluchestan province, Iran, close to the border with Pakistan, with a duration of about 25 seconds. The earthquake occurred at an intermediate depth in the Arabian plate lithosphere, near the boundary between the subducting Arabian plate and the overriding Eurasian plate at a depth of about 80 km.

The 2014 Eketāhuna earthquake struck at 3:52 pm on 20 January, centred 15 km east of Eketāhuna in the south-east of New Zealand's North Island. It had a maximum perceived intensity of VII on the Mercalli intensity scale. The magnitude 6.2 earthquake was followed by a total of 1,112 recorded aftershocks, ranging between magnitudes 2.0 and 4.9.

References

- ↑ Goines, David Lance. "Earthquake Weather".

- ↑ Robinson, Russell (14 November 2002). Michael Shermer (ed.). The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience . ABC-CLIO. p. 96. ISBN 1-57607-653-9.

- ↑ "Is there earthquake weather?". FAQs – Earthquake Myths. United States Geological Survey (USGS).

- ↑ Curious cloud formations linked to quakes New Scientist, 11 April 2008. Accessed 2009-02-25.

- ↑ "A temblor from ancient Indian treasure trove?". The Times of India. 28 April 2001.

- ↑ Gup, G.; Xie, G. (2007). "Earthquake cloud over Japan detected by satellite". International Journal of Remote Sensing. 28 (23): 5375–5376. Bibcode:2007IJRS...28.5375G. doi:10.1080/01431160500353890. S2CID 129215702.

- ↑ "让你失望了,地震云并不存在" [Sorry to disappoint you, earthquake clouds do not exist]. Institute of Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences . October 2017.

- ↑ "Curious cloud formations linked to quakes" . New Scientist. 11 April 2008.

- ↑ Monthly Weather Review. War Department, Office of the Chief Signal Officer. 1919. pp. 180–181.

- ↑ "Temperature rises hint at earthquake prediction". New Scientist. December 14, 2001.

- ↑ "Atmospheric temp spiked before Japan earthquake". Discover Magazine. May 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Link Between Earthquakes and Tropical Cyclones: New Study May Help Scientists Identify Regions at High Risk for Earthquakes". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ↑ "Hurricane may have triggered earthquake aftershocks". Nature. Retrieved 2013-04-22.