Hoodoo is a set of spiritual practices, traditions, and beliefs that were created by enslaved African Americans in the Southern United States from various traditional African spiritualities and elements of indigenous botanical knowledge. Practitioners of Hoodoo are called rootworkers, conjure doctors, conjure men or conjure women, and root doctors. Regional synonyms for Hoodoo include rootwork and conjure. As a syncretic spiritual system, it also incorporates beliefs from Islam brought over by enslaved West African Muslims, and Spiritualism. Scholars define Hoodoo as a folk religion. It is a syncretic religion between two or more cultural religions, in this case being African indigenous spirituality and Abrahamic religion.

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing.

The Stono Rebellion was a slave revolt that began on 9 September 1739, in the colony of South Carolina. It was the largest slave rebellion in the Southern Colonies, with 25 colonists and 35 to 50 African slaves killed. The uprising's leaders were likely from the Central African Kingdom of Kongo, as they were Catholic and some spoke Portuguese.

"Children of the plantation" is a euphemism used to refer to people with ancestry tracing back to the time of slavery in the United States in which the offspring was born to black African female slaves in the context of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and Non-Black men, usually the slave's owner, one of the owner's relatives, or the plantation overseer. These children were often considered to be the property of the slave owner and were often subjected to the same treatment as other slaves on the plantation. Many of these children were born into slavery and had no legal rights, as they were not recognized as the legitimate children of their fathers. The men who fathered these children often used their power and authority to force themselves upon the black females who were under their control.

Brookgreen Gardens is a sculpture garden and wildlife preserve, located just south of Murrells Inlet, in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The 9,100-acre (37 km2) property includes several themed gardens featuring American figurative sculptures, the Lowcountry Zoo, and trails through several ecosystems in nature reserves on the property. It was founded by Archer Milton Huntington, stepson of railroad magnate Collis Potter Huntington, and Anna Hyatt Huntington, his wife, to feature sculptures by Anna and her sister Harriet Randolph Hyatt Mayor, along with other American sculptors. Brookgreen Gardens was opened in 1932. It was developed on property of four former rice plantations, taking its name from the former Brookgreen Plantation, which dates to the antebellum period.

Pierce Butler was an Irish-born American politician who was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. Born in the Kingdom of Ireland, Butler emigrated to the British North American colonies, where he fought in the American Revolutionary War. After the war, he served as a state legislator and was a member of the Congress of the Confederation. In 1787, he served as a delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention, where Butler signed the Constitution of the United States; he was also a member of the United States Senate.

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not enslaved. However, the term also applied to people born free who were primarily of black African descent with little mixture. They were a distinct group of free people of color in the French colonies, including Louisiana and in settlements on Caribbean islands, such as Saint-Domingue (Haiti), St. Lucia, Dominica, Guadeloupe, and Martinique. In these territories and major cities, particularly New Orleans, and those cities held by the Spanish, a substantial third class of primarily mixed-race, free people developed. These colonial societies classified mixed-race people in a variety of ways, generally related to visible features and to the proportion of African ancestry. Racial classifications were numerous in Latin America.

Antebellum South Carolina is typically defined by historians as South Carolina during the period between the War of 1812, which ended in 1815, and the American Civil War, which began in 1861.

Partus sequitur ventrem was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that children of enslaved mothers would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property (chattels), as well as the common law of personal property; analogous legislation existed in other civilizations including Medieval Egypt in Africa and Korea in Asia.

Mary Edmonson (1832–1853) and Emily Edmonson, "two respectable young women of light complexion", were African Americans who became celebrities in the United States abolitionist movement after gaining their freedom from slavery. On April 15, 1848, they were among the 77 slaves who tried to escape from Washington, D.C. on the schooner The Pearl to sail up the Chesapeake Bay to freedom in New Jersey.

Living in a wide range of circumstances and possessing the intersecting identity of both black and female, enslaved women of African descent had nuanced experiences of slavery. Historian Deborah Gray White explains that "the uniqueness of the African-American female's situation is that she stands at the crossroads of two of the most well-developed ideologies in America, that regarding women and that regarding the Negro." Beginning as early on in enslavement as the voyage on the middle passage, enslaved women received different treatment due to their gender. In regard to physical labor and hardship, enslaved women received similar treatment to their male counterparts, but they also frequently experienced sexual abuse at the hand of enslavers who used stereotypes of black women’s hypersexuality as justification.

The history of slavery in Kentucky dates from the earliest permanent European settlements in the state, until the end of the Civil War. In 1830, enslaved African Americans represented 24 percent of Kentucky's population, a share that had declined to 19.5 percent by 1860, on the eve of the Civil War. Most enslaved people were concentrated in the cities of Louisville and Lexington and in the hemp- and tobacco-producing Bluegrass Region and Jackson Purchase. Other enslaved people lived in the Ohio River counties, where they were most often used in skilled trades or as house servants. Relatively few people were held in slavery in the mountainous regions of eastern and southeastern Kentucky; they served primarily as artisans and service workers in towns.

The Choctaw Freedmen are former enslaved Africans, Afro-Indigenous, and African Americans who were emancipated and granted citizenship in the Choctaw Nation after the Civil War, according to the tribe's new peace treaty of 1866 with the United States. The term also applies to their contemporary descendants.

Elizabeth Hemings was a female slave of mixed-ethnicity in colonial Virginia. With her owner, planter John Wayles, she had six children, including Sally Hemings. These children were three-quarters white, and, following the condition of their mother, they were considered slaves from birth; they were half-siblings to Wayles's daughter, Martha Jefferson. After Wayles died, the Hemings family and some 120 other slaves were inherited, along with 11,000 acres and £4,000 debt, as part of his estate by his daughter Martha and her husband Thomas Jefferson.

The 1842 Slave Revolt in the Cherokee Nation was the largest escape of a group of slaves to occur in the Cherokee Nation, in what was then Indian Territory. The slave revolt started on November 15, 1842, when a group of 20 African-Americans enslaved by the Cherokee escaped and tried to reach Mexico, where slavery had been abolished in 1829. Along their way south, they were joined by 15 slaves escaping from the Creek Nation in Indian Territory.

Slavery in Maryland lasted over 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to St. Mary's City, to its end after the Civil War. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia, slavery declined in Maryland as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco as the chief commodity crop, as the market for cash crops was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as England's economy improved, fewer came to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

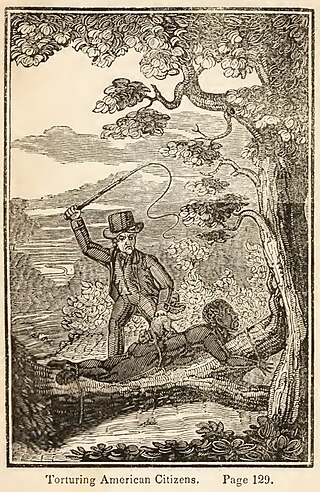

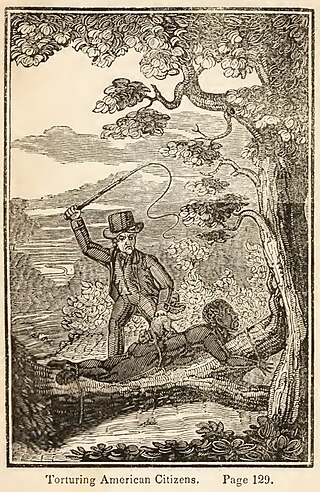

The treatment of slaves in the United States often included sexual abuse and rape, the denial of education, and punishments like whippings. Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again.

Slaves in the Family (1998) is a biographical historical account written by Edward Ball, whose family historically owned large plantations and numerous slaves in South Carolina.

African American slave owners within the history of the United States existed in some cities and others as plantation owners in the country. During this time, ownership of slaves signified both wealth and increased social status.